New Yorkers have pretty much always felt elegiac about the transformation of their city, with alarmist peaks every half-century or so. (And given that we’re now approaching the half-century anniversary of the alarming start of the last prolonged New York’s–going–to–hell era, our present Wall Street horror show looks uncomfortably familiar.) Although Henry James was a New Yorker only briefly and involuntarily, as a child in the 1840s and 1850s, and chose to live most of his life in Europe, people think of him as a chronicler of New York. And that’s because of two books—the novella Washington Square, set in the quaint Knickerbocker burg of his childhood, and the nonfiction The American Scene, which contains his melancholic and disgusted 40,000-word account of returning at age 61 to an utterly transformed New York.

In the time since James was a boy, the city’s population had grown from 500,000 to almost 5 million, resulting in a “consummate monotonous commonness, of the pushing male crowd, moving in its dense mass,” a monstrous incarnation of the “will to move—to move, move, move, as an end in itself, an appetite at any price.” Skyscrapers of 20 and 25 stories (“the detestable ‘tall building’ … and … its instant destruction of quality in everything it overtowers”) had arisen, and the underground train system (“the desperate cars of the Subway”) had just opened. “The terrible town,” this “remarkable, unspeakable New York,” now had a large Jewish ghetto in which the streetside fire escapes created “a little world of bars and perches and swings for human squirrels and monkeys.”

“I have the imagination of disaster,” James wrote elsewhere, not long before his brief return to New York, “and see life as ferocious and sinister.”

By the 1960s, middle-class New Yorkers were not merely saddened by their city’s coarse, exotic new hurly-burly, they felt besieged, in fear for their lives as well as their lifestyles. The disaster felt actual. Americans at large were discombobulated, of course, between 1964 and 1968, by several sudden changes—the war in Vietnam, the counterculture, the spasms that followed the civil-rights movement. But New York at the same time entered its own particular perfect storm—radical economic and demographic change, plus governmental dysfunction, plus an increase in violence so exceptionally steep and sudden it was almost as if war had broken out.

Imagine the unsettling Rip Van Winkle sensation of being a New Yorker in 1968. Two decades earlier, the city had been a thoroughly working-class place, with more manufacturing jobs than anywhere else in America, but most of those factories and their jobs had disappeared, leaving a city of office workers and the poor. And now the white-collar good times were looking iffy: At the beginning of 1966, Wall Street’s postwar boom reached its top. In just eight years, between 1960 and 1968, the city’s population had gone from 14 percent to 20 percent black. And during the same eight years, murders in the city had increased from about one a day to nearly three. In the winter of 1966, the subways and buses were shut down by a strike, followed over the next two years by a sanitation strike and two teachers’ strikes. All were bitter—especially the second teachers’ strike, which grew out of a fight between mostly Jewish teachers and mostly black parents over community control of Brooklyn schools.

But if you were young or youngish and had a sense of fun or adventure, it was the best of times as well as the worst. This magazine in its early years specialized in chronicling local crimes and life going haywire, yes, but catered just as obsessively to the eager new mob of proto- yuppies and bourgeois bohemians gorging on the swingy new New York, the people scrambling to eat the best food and wear stylish clothes and buy cool tchotchkes, to see the smart new art and movies and plays and comedians. In 1968, Elaine’s was still new, and in the Fillmore East’s first two months of existence Janis Joplin, the Doors, the Who, Frank Zappa, Traffic, and Jefferson Airplane all performed.

In a Times article that year about what a “startlingly expensive place to live” New York had become, the reporter marveled at the nutty Manhattan prices: On the West Side, for God’s sake, six-room co-ops were selling for $50,000 and “unrenovated brownstones” for $100,000—around $300,000 and $600,000 in today’s dollars.

And while the cohort that essentially dreamed up contemporary New York (and, not coincidentally, New York) were mostly members of the nameless generation that came of age between V-J Day and the creation of the Mets, there was a huge pool of younger would-be neo–New Yorkers in the pipeline, drawn to the sexy flicker and buzz of the groovy, glamorizing metropolis: In 1968, the oldest baby-boomers were just graduating college and the youngest were just starting school.

The nationally branded version of “the late sixties” may have been mainly about flowers and sunshine, but the New York edition was edgy, even grisly, always embedded with the imagination of disaster—that is, New Yorkier. Elsewhere the new romantics were escapists, dreaming of Arcadia; here, the model was more Weimar Republic, a dystopian Utopia. Cabaret, after all, became a Broadway smash two years before Hair opened. Andy Warhol’s Factory was a dark place. The archetypal New York band was Lou Reed’s Velvet Underground, singing songs about sadomasochism, transsexuals, and heroin. The city’s best-remembered and most important moment of sixties social protest wasn’t a well-planned antiwar march or tripped-out Be-In but a spontaneous riot by homosexuals outside a Mafia-owned dive in the Village.

In other words, the Beat-inflected hipsters of New York raced through or entirely skipped the peace-and-love phase. And in the seventies, the best of times got more so—when Saturday Night Live and CBGB were brand new, I rented a sweet East Village apartment with two exposed-brick bedrooms and a working fireplace for $410—and so did the worst of times. In fact, they started to feel a little like end-times. New York City’s budget was so out of whack by 1975 that it couldn’t sell its municipal bonds, and 38,000 municipal workers (including 5,000 cops) were furloughed—the first such layoffs since the Great Depression. Garbage piled up in enormous stinking heaps. Subway cars lacked air-conditioning and were covered in graffiti.

On Easter Sunday in 1976 at St. John the Divine, the Episcopal bishop Paul Moore Jr., one of the city’s final Wasp titans (and, we learned this year, a secret homosexual), delivered the last sermon to which New Yorkers paid close attention. “Great hulks of buildings stand abandoned and burned,’’ he preached. “Look over your city and weep, for your city is dying. Be part of the rising, not the dying.” A pious new president of the United States was nominated at Madison Square Garden a few months later, and when he visited the South Bronx for a photo op the following year, the iconic images looked like Beirut. Exactly a week after Jimmy Carter went to Charlotte Street, during the second game of the World Series at Yankee Stadium, Howard Cosell delivered his voice-over to an ABC aerial shot of the neighborhood: “Ladies and gentlemen, the Bronx is burning.”

“Look over your city and weep, for your city is dying.”

But we danced by the light of the fires. As the Bronx was burning, its sons—D.J. Kool Herc, Grandmaster Flash, Afrika Bambaataa—were giving birth to the most important new popular musical form of the last 40 years. And in the four-mile-long fillet of Manhattan from the Park to the new World Trade Center, Weimarized New York, post-disaster but pre-apocalypse, thrived, in its fashion. Between 1975 and 1978, when the city’s disintegration was at its most vivid and apparently irremediable, Studio 54 and the Mineshaft and the Mudd Club and Plato’s Retreat and Mortimer’s and Tavern on the Green all opened, as did the Palace on East 59th, famous exclusively for being the priciest restaurant ever. The 1977 blackout, complete with looting, didn’t slow down the party. A kind of willfully childish gaiety reigned. Again, Henry James saw it coming 70 years earlier—a city “so nocturnal, so bacchanal, so hugely hatted and feathered and flounced, yet apparently so innocent.”

It was at this bleak but giddy moment that Rupert Murdoch’s sudden appearance (in 1976 and 1977, he bought the Post, the Voice, and this magazine) reinforced the local sense that New York was falling to pieces, and being sold off for parts. Murdoch’s Post—manic, loud, prurient, shameless, proudly unrespectable, finding entertainment in the hideous—was both an appalling funhouse mirror and an absolutely accurate reflection of the city.

For reasons that made no rational financial sense, Murdoch was besotted by New York, and by the idea of owning a sort of postmodern parody of a rough-and-ready tabloid. I’ve always been fond of Murdoch, despite everything, partly because he made a big, risky bet on this city at its grottiest, ultra-bathetic state, an enthusiastic out-of-towner who came in and bought low just as I, in my own tiny way, was doing the same. Collectively, the moving and shaking of Murdoch and the hip-hop pioneers and the would-be artistes living in the rougher precincts of lower Manhattan (as well as a few white knights of the Establishment like Felix Rohatyn) amounted to the first stirrings of the phoenix in the ashes.

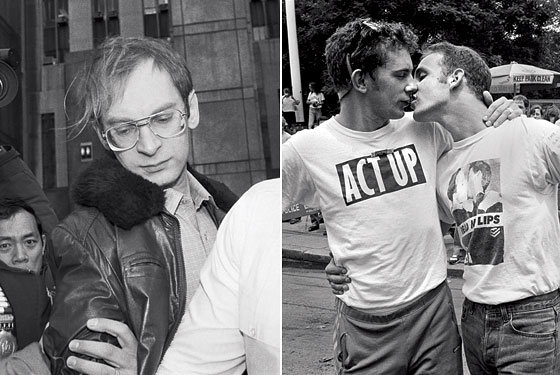

Not that we knew it then. And the rebirth occurred neither quickly nor unambiguously. Among these last 40 years, the most pivotal may have been 1982. I remember the May morning I read the first Times story about the mysterious sexually transmitted illness infecting gay men. Nearly half of the 335 known cases, the article said, were in New York City. Fourteen libertine years had passed since 1968—as it happens, exactly as long as the actual Weimar Republic lasted.

But just as one era of ecstatic, heedless, devil-may-care New York self-indulgence was about to end, another would begin. In August 1982, the great bull market of the eighties and nineties took off. Over the next eighteen years, the Dow would increase fifteenfold. The eighties were not exactly smooth sailing for New York: aids became epidemic, killing tens of thousands; crack appeared, ravaging numberless lives and whole neighborhoods; and murders increased by 62 percent between 1985 and 1990, to more than six a day. Yet even though most of the metrics of decent urban life got hellishly worse before they got better, as the nineties began, more of New York was part of the rising than the dying.

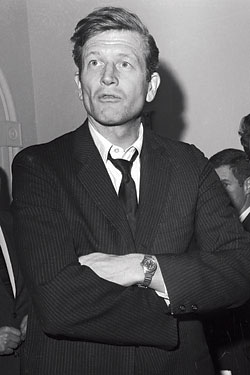

Without the prosperity of the eighties and nineties, and without the chastened rightward tacking of our mayoral politics—reactionary? revanchist? sensible? all of the above?—we wouldn’t now be recounting a story with a happy(ish) ending. John Lindsay was the last proudly, charismatically liberal leader of New York, and while he inherited a fiscal mess and truculent municipal unions, his mayoralty—from 1965 to 1973, just as New Yorkers were being mugged by reality (and muggers)—did a lot to make old-school liberalism synonymous with namby-pamby profligacy and incompetence. And so for the last 30 years, excepting the brief interregnum of David Dinkins, our putatively super-liberal city (which Richard Nixon, by the way, lost in 1972 by a mere 3 percent) has elected hardheaded mayors from the center and center-right: Ed Koch, Rudy Giuliani, and Mike Bloomberg.

One big change leads to another. Murder and other crimes went down by 40 percent all over America during the nineties, the result of many factors—fewer people of crime-committing age and higher incarceration rates undoubtedly, economic growth and legal abortion possibly. But only in this city was murder reduced by 78 percent since 1990, and almost half that drop came in just two years, from 1993 to 1995. It’s literally fantastic, the closest thing to a miracle I’ve ever seen. And most of those extra lives saved in New York are inarguably the result of our political spine-stiffening in the eighties and nineties, which led to a much bigger and more aggressive and better-managed NYPD.

The main idea of liberalism has been vindicated.

For New York, policing and prosecution were, like war, the continuation of politics by other means. And the great counterintuitive irony is that the eradication of crime, empowered by post-sixties-liberal political toughness, has achieved two great goals of the left: The tens of thousands of victims and families spared have been overwhelmingly poor and black and Hispanic, and the main idea of liberalism—that government intervention is essential to making life better—has been vindicated.

And each big change leads to still another. Of course, an advance guard of bourgeois bohemians was trickling into déclassé working-class neighborhoods like Park Slope well before Bill Bratton took over the NYPD. Gentrification was coined in the sixties, around the same time as SoHo and a few years before TriBeCa. The Times magazine, in a 1979 story called “The New Elite and an Urban Renaissance,” made the new phenomenon official: “People often snicker when they first hear of it. A renaissance in New York City? The rich moving in and the poor moving out? The mind boggles at the very notion.”

But the gentrification process was gradual and spotty until crime started plummeting. It was the radical increase in security, both real and perceived, that uncorked the flood tide of young and youngish white college graduates from Manhattan into the Lower East Side and Harlem and vast stretches of Brooklyn during the nineties and aughts. In 1990, Harlem was 1.5 percent white; today it’s probably close to 9 percent. The presence of yuppies and bobos, white and otherwise, attracts more of their kind, which tends to bring more security, which in turn leads to more yuppies and bobos. That boggled 1979 mind would be stunned into speechlessness by the parallel-universe vision of New York on the eve of 2009—the graffiti-free subways, the civilized perfection of Central Park and (even more) Bryant Park, the cutesy snow globe that is Times Square, $3 million houses in Fort Greene, curb-to-curb hipsters in the Lower East Side, gourmet food and Swedish furniture in Red Hook. And so on.

The progress of gentrification wasn’t only a result of the precinct-by-precinct diminution of crime. My bit of Brooklyn, Carroll Gardens, was a very safe (and almost entirely white) working- and middle-class quarter when I arrived in 1990 with my wife and baby daughters. Nor were we exactly pioneers; a couple of editors had already renovated our brownstone. But at some moment between the eighties, when I knew exactly two people in Brooklyn, and the end of the century, when at least half the younger people of my acquaintance were living there, the borough not only lost most of its stigma but acquired an unprecedented aura of stylishness. It was an emergent rebranding as alt-NYC, driven first by the invisible hand (cut-rate real estate just across the river) and then by the self- propelling presence of more and more People Like Oneself. I can peg the tipping-point moment fairly precisely in my neighborhood: As I waited to vote in 1992, I was the demographic outlier in the polling-place crowd of retired longshoremen and their relatives; when I returned in 1996, almost every voter in the place, I swear, was some kind of writer or graphic designer or MTV producer a decade or two my junior. And the following year, all at once, Smith Street changed from a dreary Poughkeepsiesque stretch where we went only to catch the F train to—abracadabra!—a groovy restaurant row thick with recently expatriated young Manhattanites. Manhattan is not over, certainly, but for the city’s “creative class” New York is no longer a one-borough town. Brooklyn has become St. Paul, maybe, to Manhattan’s Minneapolis, rather than Compton and Glendale to its Hollywood and Beverly Hills.

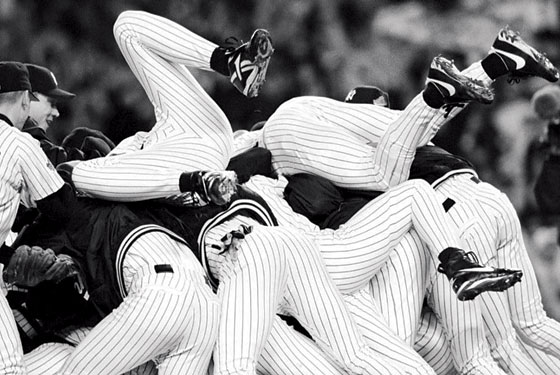

As the city’s well-to-do have become more numerous, more widespread, and more well-to-do, money has become more than ever the central New York subject. Not that art and ideas and love and baseball were the sole preoccupations of the city in any of the old days. A century ago, a good deal of the wellborn Henry James’s horror at the new city involved its vulgar celebration of cash: “money in the air, ever so much money,” “the colossal greed of New York,” “the crudity of wealth,” the “candid look of [houses] having cost as much as they knew how.” (Mr. James, let me introduce you to Mr. Trump and Mr. Schwarzman … ) But it was during the Gilded Age that Jacob Riis published How the Other Half Lives, his startling chronicle of New York’s poor. It’s hard to imagine an equivalent exposé today that would so shock the conscience of respectable New York. Indeed, the very title of Riis’s book now connotes the opposite—the lifestyles of the rich and famous.

Our present Gilded Age began in the eighties. The crash of 1987 didn’t end it, nor the recession of 1990, nor the bursting of the tech bubble in 2000, nor the attacks of 2001, nor the new hegemony of “sustainability” as a governing idea. The spell of big money and super-high-priced things has lingered on and on. We are bedoozled, to use a slang term from the century of the original Gilded Age. That first famously money-mad New York–centric era is said to have ended with the Panic of 1893. Which began with bank failures. And led to an economic depression that lasted several years.

So maybe the final chapter of this 40-year novel of the city will include another big turn of the screw, with some of the city’s overmonied about to be kicked to the curb and brought down to earth. And even if the limos keep rolling, and people keep lining up for $1,000 Per Se meals, don’t we prefer the main isotope of civic resentment and mistrust to be derived from class rather than race?

Twenty-five percent of New Yorkers today are black, up only modestly from 40 years ago. But since then we have nevertheless, rather strikingly, become a city of color, from almost two-thirds white in 1968 to only a third today. So New York has grown much less dangerous, much less bedraggled … and—such a great irony—much less white. Non-Hispanic whites are now just another minority in this city of minorities. At the same time, the spectacularly awful moments of racial discord of the nineties—when a black man in Crown Heights murdered a Jew in revenge for the accidental killing of a black child by a Hasidic driver, when cops killed Amadou Diallo and tortured Abner Louima—now seem like the ugly twilight moments of an era. Indeed, one of the silver linings of the terrorist attack in 2001 was that New York’s racial anxieties were suddenly subordinate to our new common fear of crazy foreigners who wanted us all to die.

New York’s racial anxieties were suddenly subordinate to our new common fear.

And speaking of foreigners: The final dramatic shift in the nature of the city since 1968 derives from the huge and strangely rather underheralded influx of people from abroad. As it happens, all the black victims in those awful nineties incidents were immigrants—7-year-old Gavin Cato was from Guyana, Diallo from Guinea, and Louima from Haiti. The foreign-born fraction of New York is now nearly 40 percent, more than double the figure of 1968—and more than three times as many as in America at large. During the last four decades New York’s immigrant population has gone from its smallest since the early 1800s to its highest since 1910.

Inevitably, babies have been thrown out with the bathwater. I do slightly miss the loss of the seventies bohemia, even though I was one of the objects of those DIE YUPPIE SCUM graffiti in the East Village at the time. When it lacks for grit and the Man and a frisson of danger, bohemianism becomes just another style. On the other hand, I can’t join the latter-day Bizarro World Jamesians who find Times Square insufficiently squalid, and regret that Avenue C and Rivington Street are no longer open-air heroin markets. Me, I’ll settle for the High Line, a totally 21st-century nostalgic embrace of New York decay and desolation, a sweet, slightly smug Piranesianism that recalls 1968 from the arm’s-length comfort of 2008.

Of course, one lesson of the last 40 years is that it’s folly to predict the future by extrapolating in a straight line from the present. Pendulums tend to keep swinging. History doesn’t end. There’s always the possibility of another terrorist attack. Half the drop in crime was a mysterious gift, and it could mysteriously shoot back up again.

While urban rejuvenation of an organic, ground-up kind has worked wonders, we’ve apparently lost the ability to accomplish heroically scaled, top-down development of the Rockefeller Center and Robert Moses sorts: The debacle at ground zero (and Moynihan Station) is a case study in New York dysfunction, a reminder of the bad old pre-311 days. Just as George Bush failed to take advantage of the post-9/11 moment to forge a radically sensible new national energy policy, our local political and business leaders failed to seize the opportunity in 2001 and 2002 to turn the World Trade Center site into something grand and good.

And then there’s this Panic of 2008. What’s happening now—unlike 1974, 1987, 1990, and even 2001—does look and feel not like a mere correction, but rather a much larger historical turn, the end of a hypercapitalist era. A chastened, more prudent Wall Street may be good for America and the world … but perhaps not for New York. Our local renaissance the last quarter-century was fed in large measure by all that cash gushing into the city’s economy, and by all that exuberance—cynical as well as optimistic, irrational and otherwise—coursing out of Wall Street. “This is not going to be a feel-good time,” Mayor Bloomberg said last week, as he proposed raising property taxes by 7 percent immediately.

We have been through booms and busts before. And this being the city it is, the ups and downs seem more extreme and operatic than elsewhere. We are drama queens. “Poor dear reckless New York,” Henry James wrote a century ago. But the city also, in its gimlet-eyed, show-must-go-on way, makes do and muddles through. James: “Its mission would appear to be, exactly, to gild the temporary, with its gold, as many inches thick as may be, and then, with a fresh shrug, a shrug of its splendid cynicism for its freshly detected inability to convince, give up its actual work, however exorbitant, as the merest of stop-gaps.”

What has given and (knock wood) will continue giving New York the ability to recover and regenerate? The subway system. The compactness. The fact that it’s headquarters for not just one but several of the Ur-modern industries—finance as well as fashion as well as marketing as well as media as well as art. The routine difficulty of day-to-day life that makes the city a sort of perpetually toughening boot camp. And the unstoppable inflows of variously dreamy and eager emigrants, from the rest of America and abroad, who keep coming because of the self-consciously thrilling, muscular, glamorous, universally familiar idea of New York City. This is Oz.