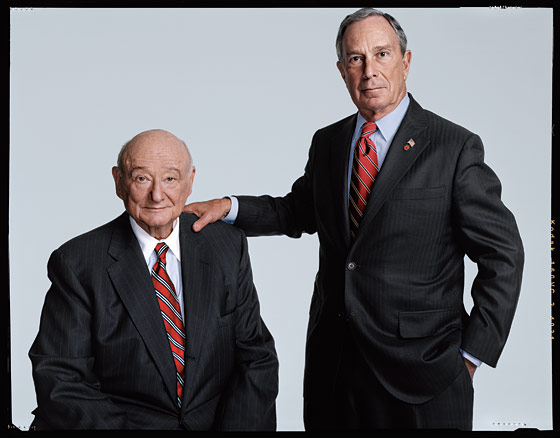

The current occupant leaned back on a plush red couch; his puckish predecessor sat in a stiff-backed chair. Michael Bloomberg and Ed Koch were in one of City Hall’s private offices, talking seriously about the issues and enemies they’ve confronted as mayor, and the changes in the city they’ve led. But their tone was as warm and relaxed as old war buddies’.

New York: You’ve both dealt with crises that threatened the city’s physical and economic survival. How worried are you by the current financial mess?

Ed Koch: Wall Street and the city will survive. The only thing to worry about is that the rich get preferred under all these programs, and the middle class comes after them. It should be the other way around. The rich should be the last to get through the eye of the needle.

Michael Bloomberg: No question, these times will be tough and we’re going to have to work together. I always say that nothing goes up forever—and that’s why we used the good times to prepare for the tough ones. So yes, these are difficult days, but we know how to get through them. We’ve done it before and will do it again.

NY: Mayor Bloomberg has said that the city made a “mistake” during the seventies fiscal debacle by allowing quality-of-life services—the Police Department, schools, parks—to deteriorate.

EK: You can’t call it a mistake! It was a question of resources. The reason we got where we got is we spent money we didn’t have. That started in the last year of Wagner’s administration and went to its zenith in the Lindsay and Beame administrations.

MB: Ed was elected in 1977 to get the city back on its feet, and he did a spectacular job. The lesson is, when you walk away from these investments during tough times, you walk away from your future—and we won’t do that.

NY: What did starting in the middle of a crisis—for Mayor Koch, the fiscal disaster; for Mayor Bloomberg, the aftermath of 9/11—teach you about being mayor?

EK: When I was elected, I said to myself, Can I do this? Seven people ran, and some of them were extraordinarily capable. And I said to myself, But the people picked me! For good or bad. And now I have to do my best. And I had only one or two sleepless nights in twelve years. Because I thought to myself, It’s working! The key was, get people to follow you. I used to say, to crowds—because I went out in the streets a lot—“If you follow me, I will lead you across the desert!” That’s a nutty thing. But they followed me! And that was key, because you had to demand great sacrifice from the people of the city. And the people who had to sacrifice the most were the poorest. Because that’s where the budget goes. Two-thirds of the budget. All the left-wingers, the Village Voice people, yelled, “He’s balancing the budget on the backs of the poor!” And I said, “Who do we spend the budget on?”

MB: I’d argue that Ed Koch—and Michael Bloomberg, both—had a real advantage coming in. Because we both came in in difficult times, and it is easier to govern in difficult times than it is in flush times. You have more leverage with legislatures; the public is more sympathetic, they know it’s not easy and they might not be happy with your decision, but what they want is somebody they think is at least trying to do what’s right. One year I closed half a dozen firehouses—nobody ever lost their job! The firefighters, we moved them to where the public had moved! We should be doing that every year! I raised taxes—our police and firefighters wanted to get paid, surprise, surprise. And I put a smoking ban in—everybody’s gonna live longer. My approval was down to 25 percent, but on the questions—does he care? Is he honest? Is he hardworking?—75 percent approval. People want a genuineness. I think it’s useful, also, to be a character. Ed was better at that than I am. I tend to not be as expansive.

EK: My personality was such, you hit me, I hit you back. [Laughs] It’s different with Mike. Much more respectful of people. If I would point to one thing, of all the things he’s done, I would say his greatest achievement is reducing racial animosity.

NY: Race relations have gone from nonstop turmoil in the seventies to nearly placid today. There must be more to it than a different mayor.

EK: When I came in, I had to cut the budgets. And it’s primarily black and Hispanic citizens of New York City who are suffering.

MB: The maturity of our society is, you can discuss things like the crime rate in the city, and if you look at the ethnicity of murder victims and murder perpetrators, crime is a minority problem. It is probably tied to economics—I think if you went to West Virginia, you’d find that the ethnicity is white Protestant. Here it is black and Latino. When I go to a black church, or go to a Latino church, they appreciate the fact that you’re going after two societal problems where they are the primary victim: poor schools, high crime. In other days, you couldn’t say that without being accused of being racist. Today, you can talk about it. You do have to be a little bit sensitive. After I got elected, before I took office, somebody had invited me to a dinner of 100 Black Men. I couldn’t go. The guy said, just before I hung up, “We’re gonna have Al Sharpton there.” I stopped and I said, “I tell you what: I can only come for a drink. But you have the cameras and Al Sharpton meet me at the door, have Al show me around, have Al shake my hand on the way out, and I will change my schedule.” That’s exactly what happened. And it ended this animosity between parts of the black community that Al represented and the mayor’s office that had gone on for a long time.

EK: He’s not giving himself enough credit. I know Al Sharpton. The fact is, I had him arrested right outside this room!

NY: Do Democrats still control the city?

EK: This is a Democratic town. But it is not the kind of operation that existed years ago that was directed by a few people. People in the city of New York are Democrats, in the sense that they believe they’re responsible for the welfare of other people who live here. I’m proud of that. I believe that as well.

MB: People say, Giuliani got elected and Bloomberg got elected, therefore [the Democrats are less powerful]. Giuliani got elected because people wanted a change, any change. David Dinkins is a very nice guy, but people were not happy.

EK: Crown Heights.

‘It is easier to govern in difficult times than in flush times.’

—Michael Bloomberg

MB: Crown Heights. Bloomberg got elected because he spent $75 million and his opponent self-destructed. Maybe a few other things, but basically that was it. That does not mean the next mayor of the city of New York isn’t very likely to come from the Democratic machine, somebody who worked their way up. There’s always a chance for an aberration. But it’s not a good bet. It’s like betting on the lottery as a business strategy instead of going to college.

NY: Another major change in the political dynamic is the power of the unions—weaker locally, but stronger in Albany.

MB: What is different from the olden days—at least what I’ve read about the olden days—is the unions telling their members how to vote. That’s gone, if it ever existed. They don’t pay any attention. The Democratic machine, gone. The place the machine still works is in the legislative offices.

EK: The area that always concerned me was that in Albany, they would impose higher pension costs to be borne by the city out of its own monies. Huge dollars, hundreds of millions.

MB: [Rolling eyes] We negotiate with them, then after the deal, they go up to Albany and get something else!

EK: Right. The way it worked in Albany—and I suspect it still works the same way—the Assembly, which is Democratic, is dominated by the teachers union and District 37. The Senate, which is Republican, is dominated by the teachers union—they’re in both places—

MB: Yup. Yup.

EK: —and by the cops and the firefighters. I remember going up to Albany to fight the pension, and I meet two firefighters. And they liked me, the cops and the firefighters, because I always gave them, in collective bargaining, a fraction more, on the basis that they could lose their lives in protecting people.

MB: “Uniformed services differential” we call it today. We’ve never been able to get rid of it. And now DC 37 wants it, which is why we don’t have a contract with them.

EK: Tell them, when they get a uniform, you’ll consider it!

MB: They’ll take the uniforms—and they’ll want to carry guns, too. [Laughter] I’ll give you an example of the worst thing I think has happened, the most disgraceful thing in the last six and a half years. In April, in the middle of the night, with no notice, no hearings, no publicity, the Republican Senate and the Democratic Assembly passed a law, which the governor signed, which prevents us from using teacher performance in granting tenure. Now, tenure for public-school teachers is about as stupid a concept—these people are not advancing man’s body of knowledge, they have civil-service protection anyways, they don’t need to be able to say stupid things or write stupid things like some college professor does.

EK: The State Legislature is a cesspool. I hate them.

MB: Don’t pull your punches. Tell us what you think.

EK: And you can’t get rid of them.

NY: The middle class that existed in the seventies continues to be squeezed out of the city. Is that tragic or simply inevitable?

MB: No. It’s not happening. It’s going in the other direction. Because schools are better. The middle class is not moving out. The problem we have is the reverse: that there are a lot of people who believe, me included, that you have an obligation to find, for example, housing for those who are with us during the tough times, who are at the bottom of the economic ladder, education ladder, whatever.

NY: In the seventies and eighties, New Yorkers weren’t just sure we were better and smarter than the rest of the country—we were proudly, defiantly different.

MB: Arrogant.

NY: Now it seems that attitude is fading, and we’re content to fit in with the rest of the country.

MB: I’m not sure that’s true. What is clearly true is that people from around the country now come to New York, don’t find us arrogant, don’t find it dangerous, don’t find it expensive, don’t find it scary. We’ve worked very hard at bringing events here that spread the message. The Republican convention was a godsend for us. I didn’t want to get the Democratic one; I wanted the Republican one. Why? ’Cause the Democratic one would bring people who come to big cities. The Republican one brought people here who knew about New York from David Letterman. And when they walked out, they never saw any of the protesters, they never saw any of the craziness that the New York Times writes about. They say New Yorkers were wonderful.

The people who had to sacrifice the most were the poorest. Because that’s where the budget goes.

NY: Tourists have worn down our edge?

EK: I don’t think tourists have worn us down. I think that we’re genuinely appreciative—

MB: Absolutely.

EK: —of what the rest of the country did when it came to our aid [after September 11].

MB: I have tried to downplay the arrogance because of the 9/11 thing, but also because I think it’s the right thing to do. And, as Henry Kissinger says, it has the added advantage of being true—that we aren’t that much better, or any better.

NY: What are the lingering effects of 9/11?

MB: The families are very different than everybody else. The families haven’t forgotten. The danger for the rest of us is that we are in fact forgetting. [September 11] is not a big thing in our lives—sadly. We are doomed to repeat tragedies if we don’t learn anything.

EK: It’s not possible to continue constantly in fear or sorrow. Otherwise, you can’t get things done. What’s happened is very normal. I believe we are facing a 30-year war against Islamic terrorism. But you also have to live your life. And that is what we are doing in the city of New York.

MB: Did you review the new Woody Allen film?

EK: I did.

MB: Did you like it?

EK: I liked it.

MB: It just came to mind because they’re not worried about anything. It’s a love story. It’s a chick flick, I think. Though what’s-her-name is to die for.

EK: Penélope Cruz.

MB: Penélope Cruz is to die for! But it’s exactly the reverse of this—it was what Ed said, getting on with life. Drink and art and sex!

NY: Present company excepted, which New York mayor do you most admire?

EK: La Guardia!

MB: I can’t answer. I never knew Beame; I didn’t know Lindsay.

NY: What is Giuliani’s greatest legacy as mayor?

MB: He brought down crime and reduced corruption in welfare.

EK: I wish him well, and I’ll stop there.

NY: The city has changed a great deal, but is the practice of politics eternally the same?

EK: I ran against Westway. And I did it because all my supporters were against it. I wasn’t sure they were right, but there’s a limit to how many things you can take on that your supporters don’t approve of when you’re running … Then when the real timetables came in, Hugh Carey said, “You’ve gotta be with me on this.” So I said to him, “Listen, if I get off Westway, there’s gonna be an uproar. I’m gonna really suffer—and you have to pay for it. If you want me to get off Westway and join you, then you have to guarantee that the [transit] fare will not be raised for four years.” He said, “Are you crazy? That’s hundreds of millions of dollars!”

MB: To save a few fish!

EK: I said, “If I have to suffer—”

MB: “—you have to suffer.”

EK: He wanted it very badly, and he said okay. But then, in the third year, he imposed an increase with the rider paying. I called him up: “Hughie, you cannot do this! You gave me your ironclad assurance!” And he said, “Next time, get it in steel. Iron breaks.”

MB: Politics and governing is the art of coming up with a consensus that most of the people [can accept], or within one standard deviation of the center, and there will always be somebody four standard deviations out, and you just can’t accommodate them. Having said that, I think the art of governing is to lead rather than to do a poll and see where they are. Ed Koch—I read the papers about Ed Koch when he was mayor; I didn’t know Ed Koch then, didn’t know very much about government—my perception of Ed Koch was that he decided. He led from the front. And I’ve tried to do the same thing.

NY: Would McCain or Obama be the best next president for the city?

MB: The next president, regardless of who it is, has to face some issues that all cities face in common.

NY: But what’s your preference?

MB: Well, I’m pretty sure I know who I’m going to vote for. But I’m not gonna tell you. But in either case, the mayor of the city has to work with either one. Neither one is addressing the issues in the ways I think they should. On the big issues, there’s no simple solutions, there’s painful solutions only. Our life expectancy is worse than Western Europe, yet we pay $3,000 more for health care. Our public-school system is a disgrace. We have guns in the hands of criminals and kids all over. You go right down the list—energy independence! They want energy independence, they pass a farm bill with ethanol.

NY: Oh, come on! You care about gun control, smart energy policy, broad immigration, you believe in science—you’re an Obama voter!

MB: I don’t think I’ve heard from either candidate explicitly what they would do. I talk to both of them with some regularity. I’ve told both what I think they should do. I recommended to both who they should pick for vice-president—neither listened. It wasn’t me.

NY: Several years ago, during an event you both attended at Gracie Mansion, Mayor Koch said he’d be happy to move back in.

MB: He can run again!

NY: Mayor Koch, are you going to run next year?

EK: No.

NY: Mayor Bloomberg, are you going to run next year?

MB: My candidate is sitting right here. I’m going to work hard to convince Ed Koch to run. And if he is not willing to run, I don’t know the answer.

EK: This is the greatest job in the world.

MB: Yes. That’s correct. When a cabdriver yells, “Great job, Mayor!”—if you don’t like that, you ought to see a shrink! It’s the most fun thing of all.

More Conversations

•Gloria Steinem and Suheir Hammad

•Richard Price and Junot Díaz

•Woody Allen

•André Soltner and David Chang

•Debbie Harry and Santogold