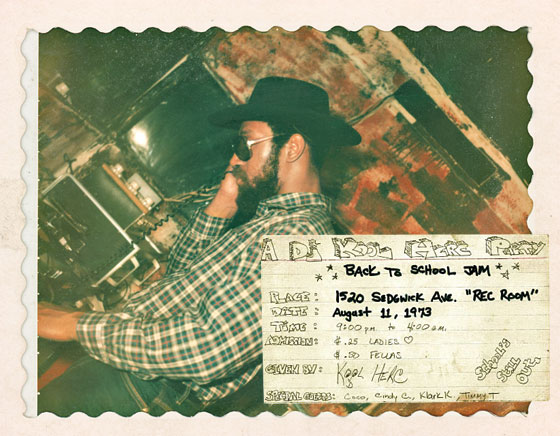

On August 11, 1973, in the rec room in an unassuming brick apartment building at 1520 Sedgwick Avenue, hard by the Major Deegan Expressway, a 16-year-old Jamaican immigrant changed pop music forever. This is the night that Clive Campbell, later known as Kool Herc, invented hip-hop at his little sister Cindy’s “back to school jam,” which was actually a moneymaking venture to fund a shopping expedition to Delancey Street.

For the hip-hop faithful, the story of that party is something close to sacred, but the bland building itself had sunk into obscurity. As had Herc himself, who never cashed in on the rhythmic innovations that ultimately led to the blingy universe of Puffy and Jay-Z. But lately both Herc and his old house have been back in the news, after a private-equity firm tried to buy 1520 and take it out of the state’s Mitchell-Lama middle-class-housing program. This would lead to higher rents, which alarmed housing activists. When they realized that this was no ordinary building, they called in Herc to help get the media’s attention, and possibly prevent the sale.

Herc hasn’t lived there in twenty years. “We still keep in touch with people from 1520,” Cindy Campbell says. “When one of the original tenants called me last year and told me that they had received notice that they had to be gone within the year, I knew we should be involved.”

On August 6, the 53-year-old Herc—still muscular, clad in a red T-shirt, and black jeans—held a press conference with Senator Chuck Schumer (who called him “LL Cool Herc” by mistake) and other politicians. It was a strange alliance, but it made the earnest topic of affordable housing more newsworthy. During an earlier press conference, Herc had said, “It’s like Graceland or the Grand Ole Opry; it’s the birthplace, where it all started from. It’s a piece of the American Dream and we just want to preserve it.”

Cindy’s back-to-school party took place in a very different Bronx, one that private-equity firms were most definitely not interested in. “I can’t speak about the rest of the country, but the Bronx in 1973 was crazy,” said Herc’s friend Coke La Rock, who also played a pivotal role that night. “Anybody that tells you different wasn’t here. Buildings were burning, Vietnam vets were coming home messed up, there were street gangs. It was like that movie The Warriors.”

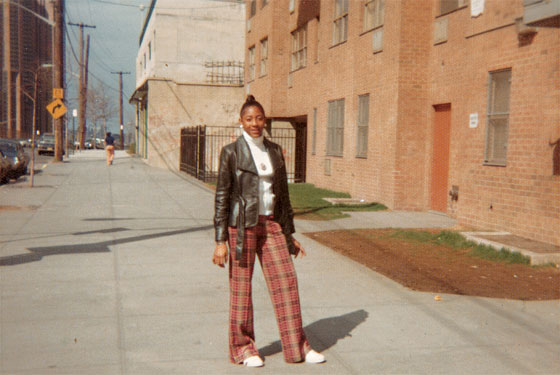

Nationwide, revolution was in the air, Afro picks were in the hair, and Fat Albert strutted Saturday mornings on CBS. Blackness was beamed onto countless movie screens as anti-heroes the Mack and Black Caesar “stuck it to the man.” The realism of Stevie Wonder’s “Living for the City” and Donny Hathaway’s “Someday We’ll All Be Free” blared from the radio.

Herc, who’d been given his nickname by friends who played basketball with him (it came from the cartoon The Mighty Hercules), was a D.J., like his father, who had a business playing at parties. “My father shared his love for music,” Cindy says. “He played everything from Nat King Cole to Pat Boone. For my dad, there was no color barrier when it came to records; good music was just good music.” Herc listened to Cousin Brucie on WABC, who played acts like Crosby, Stills & Nash and Three Dog Night.

Herc had been refining a new technique in his second-floor bedroom: He’d ignore the majority of the record and play the frantic grooves at the beginning or in the middle of the song. Herc referred to this as “the get-down part,” because this section of the song was when the dancers got excited. Utilizing two turntables and a mixer, Herc used two copies of the same record (removing the labels so others couldn’t “steal” them) to isolate and extend the percussion and bass. This became known as “the break.” It wasn’t until he was spinning at his sister’s party that he showed it to an audience.

That night, Cindy rented the recreation room for $25, and charged admission. “It was only 25 cents for girls and 50 cents for the guys,” she says. “I wrote out the invites on index cards, so all Herc had to do was show up. With the party set from 9 p.m. to 4 a.m., our mom served snacks and dad picked up the sodas and beer from a local beverage warehouse.” Herc had brought new records from a shop called Sounds and Things and had practiced for most of the week on his father’s Shure speakers.

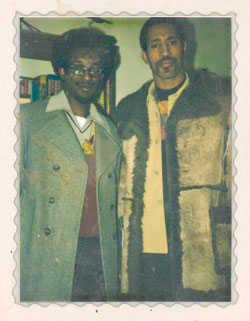

But something else, unplanned, happened that night: La Rock began “rapping.” Wearing spotless new Adidas pants from Harlem store A.J. Lester’s and sporting a fresh haircut he had gotten at Dennis’ Barbershop over on Featherbed Lane that night, La Rock picked up the mike and began talking over the blaring breaks.

“Our friends Pretty Tony, Easy Al, and Nookie Nook were all at the party,” he recalls. “At first I would just call out their names. Then I pretended dudes had double-parked cars; that was to impress the girls,” he continues. “Truthfully, I wasn’t there to rap, I was just playing around.”

Like Andy Warhol’s soup cans, what Kool Herc created in that recreation room might seem uncomplicated in retrospect, but in 1973, it was revolutionary. It was, for hip-hop, the equivalent of the Sex Pistols concert three years later at the Manchester Lesser Free Trade Hall, where audience members went on to form the Fall, the Smiths, the Buzzcocks, and Joy Division.

“Once they heard that, there was no turning back,” Herc told me ten years ago. “They always wanted to hear breaks after breaks after breaks.” It didn’t matter if that “break” was lifted from James Brown or Led Zeppelin; the dancers responded.

“Herc was the first to play break beats, which made him a force on the turntables,” said writer Nelson George, co-executive producer of the annual Hip Hop Honors for VH1. And the event became legendary. “That first party was epic,” says Grandmaster Caz, leader of the Cold Crush Brothers, who was there. “Afterwards, everybody attempted to re-create the energy of that night.” The list of those who attended the party (or at least later claimed to) reads like a Who’s Who of old-schoolers, including Grandmaster Flash, Busy Bee, Afrika Bambaataa, Sheri Sher, Mean Gene, Red Alert, and KRS-One. “I lived down the street, but when Herc put those speakers outside, you could hear them from blocks away,” says Sheri Sher of the crew Mercedes Ladies. “Later on, Herc became a hood superstar, but that night nobody knew who he was. The next day, it was a different story.”

That first party was epic. Afterwards, everybody attempted to re-create the energy of that night.

Even today, when I meet La Rock, sitting on a step next to a local bodega a few doors down from 1520, I am instantly drawn into his urban-poetic speech patterns. “To tell you the truth, we were before our time. I didn’t see it then, but I do now. Me and Herc were to hip-hop what Nicky Barnes and Frank Lucas were to drugs.” The comparison is apt: La Rock used the parties to market his primary business: selling pot. “I was never worried about Herc paying me for my services, because I was getting hustling money,” he says. “Man, at a good party I could make $1,200 to $1,700.”

Before Herc, club owners paid live bands a few hundred. Herc only charged $150 and had the spot packed. “Everybody wanted it,” says La Rock. “They had to have it.”

Soon, other kids imitated Herc, and added their improvements, like scratching. Small clubs started opening: the Black Door, Ecstasy Garage, Harlem World, the Disco Fever (it was used in the 1985 film Krush Groove). Many were firetraps, and often there were fights, but this was where the music thrived and evolved. In 1977, Herc was badly stabbed at a club called the Sparkle. After spending four weeks in the hospital, he retreated a bit from the scene.

Perversely enough, the blackout that year spawned a whole new generation. According to Grandmaster Caz in the book Yes Yes Y’all, “During the looting, everybody stole turntables and stuff. Every electronics store imaginable got hit. Every record store. That sprung a whole new set of D.J.’s.”

Meanwhile, the D.J. faded in the background as the rappers became more assertive. In order for hip-hop to be marketable by the record companies, there needed to be front men—stars. Whereas La Rock was purely improvisational, the new rappers like the Furious Five were keeping rhyme books and practicing in the mirror.

In the summer of 1979, soul singer Sylvia Robinson went to Harlem World and heard this music for the first time. Lovebug Starski was the D.J., and Robinson was enthralled. She owned a studio and a small label, Sugar Hill Records. Four months later, Robinson released the first hip-hop single, “Rappers Delight,” by the Sugar Hill Gang. The following year, Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five were also on the label.

“People respected Herc and Coke,” says Gary Harris, who ran promotions for Sugar Hill. “But by the early eighties those guys were like specters—they just weren’t visible on the scene anymore.” The scene went mainstream. In 1985, Run-DMC’s self-titled debut album went gold. And the hip-hop era had begun.

By that time, Herc had developed a crack habit. “My father died, my music was declining, and things were changing,” he once told me. “I couldn’t cope, so I started medicating. I thought I could handle it, but it was bigger than I was.”

These days, Herc won’t talk to journalists without being paid for his time. “Herc is not bitter, he’s just tired,” explains Cindy. Sitting in a garment-district coffee shop downstairs from her office, she sipped steaming tea. “He doesn’t know if you’re going to take his story and write a book about it or maybe make a movie.

“Hip-hop was Herc’s baby. But imagine that all of a sudden somebody snatched your baby from you and killed it. That’s how Herc feels sometimes.”

“I’ll be honest with you, if I was Herc, I’d be mad, too,” says D.J. AJ Scratch. Former D.J. for rapper Kurtis Blow (whose 1984 hit “Basketball” is still played at NBA games), AJ now promotes parties. “People like Grandmaster Flash and myself all took bits and pieces from him and put together our own styles. But Herc’s style of mixing records was the foundation for the entire movement.”

According to Nelson George, Herc has always been indignant toward the competition. “I remember him having resentment toward Grandmaster Flash when I first interviewed him in 1977.” Years later, when George campaigned to have Herc included on the Hip Hop Honors of 2004, he was annoyed that D.J. Hollywood was also included. “Herc was very upset.”

The day I was talking to La Rock, we ran into Herc, standing in front of his car. Herc glared at us. “I hope you’re getting paid, Coke!” he screamed. (He wasn’t.)

“What’s his problem?” I asked La Rock. “Why does he have such a bad attitude?”

For the first time during our interview, La Rock didn’t look jovial. Indeed, what kind of fool am I to attack another man’s best friend—especially in the Bronx?

“I don’t feel none of that you’re saying, because y’all didn’t make him,” he says. “All of a sudden people acting like they made Herc, but Herc is in a class of his own. No disrespect, but Grandmaster Flash, Jazzy Jay, and all those guys used to come watch us. Herc was first, and we held it down for four years. Like Frank Sinatra, me and Herc did it our way.”

The war for the future of 1520 continues, in court. When the tenant activists originally realized the building’s significance, they applied to have it landmarked, on the thought that it might keep 1520 from being moved out of the affordable-housing program. But the landmarking has been stymied so far, and wouldn’t have kept the building from being taken out of Mitchell-Lama anyway. But thanks in part to the media attention, activists did manage to get the city’s Housing Preservation Department to rule that it’s unacceptable to sell a Mitchell-Lama building for more than what its Mitchell Lama rents could support. Then the tenants tried to buy the building themselves, but they were outbid. While a restraining order keeps the sale in stasis, the activists are hoping that the economic downturn will cause the buyer to back down.

At the press conference in August, Herc stood under a handmade sign reading save the home of hip-hop. “This is not just about 1520, this is going on throughout the city,” he said, his accent thick. He might’ve lost hip-hop, but he’s trying to hold onto this. “I lived here once, and we’re not going anywhere. I’m here for the fight, and I’m not giving up.” As though it was 1973 again, and he was spinning till dawn, the crowd broke into applause.