A canon is antithetical to everything the New York art world has been about for the past 40 years, during which we went from being the center of the art world to being one of many centers. I skipped some art in which New York itself figured prominently—I hated Christo’s The Gates, and I didn’t like Richard Serra’s Tilted Arc either—and instead chose artists who threw New York curves, who changed the context of making art here. I left out the influential German artists who landed here en masse in the eighties, like clowns from a Volkswagen. There were too many, and they weren’t our clowns. I could have added Julian Schnabel; he’s a great New York huckster who gives people fits, but Jeff Koons goes him one better. Paula Cooper opened the first Soho gallery, and the Guerrilla Girls changed institutions—but omit an artwork in favor of a dealer or a group? In the end, an individual thing that made me open my eyes anew always won.

BRUCE NAUMAN, SLOW ANGLE WALK (BECKETT WALK.) 1968

Although Nauman worked mostly in L.A., his 1968 tour-de-insanity-and-inscrutability—a video of himself, striding around in his own private Monty Python sketch—embodies a fierce, build-it-out-of-yourself New Yorkiness. Nauman inspired several generations to use the body as sculpture and make art about being in the studio.

VITO ACCONCI, FOLLOWING PIECE, 1969

Acconci merged conceptual art, performance, and sexuality with a distinctly urban paranoia in Following Piece , for which he followed strangers around the streets of New York until they went into private places. He opened up a whole new dark-side poetic-conceptual realm.

PHILIP GUSTON, THE STUDIO, 1969

When the Abstract Expressionist Guston showed paintings of art materials and oafish Klansmen, he was panned—Hilton Kramer called him “a mandarin pretending to be a stumblebum”—but young New York artists understood that a new type of figuration was in the air.

SOL LEWITT, LINES, COLORS, AND THEIR COMBINATIONS (DETAIL), 1969–70

In this, one of more than 1,000 wall drawings made using simple sets of instructions like “vertical lines, not straight, not touching,” LeWitt rendered an elusive quality—thought—visible. He took the grid of the city, multiplied it, and overlaid it with other grids like a gentle Robert Moses, using New York as an idea machine.

LYNDA BENGLIS, ARTFORUM AD, 1974

Benglis took out a two-page ad featuring a photo of herself naked, holding a giant dildo to her crotch, and the art world (and even Artforum’s editors) went crazy. Post-feminism was essentially born here.

GORDON MATTA-CLARK, DAY’S END (PIER 52), 1975

The late artist’s slices out of Pier 52 created art from the ruined city itself. That served as a declaration of artistic independence—that art should be made in the world, not just shown in galleries. It also got him arrested.

JENNIFER BARTLETT, RHAPSODY, 1975–1976

Bartlett’s 987 twelve-inch painted steel plates hung frieze-style were a breakthrough of artistic ambition, process art, and feminism. Rhapsody paved the way back into forbidden territory—for this to be a painting town one last time.

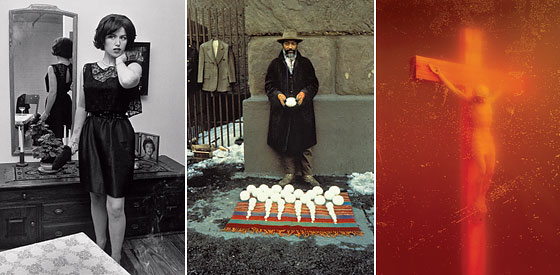

CINDY SHERMAN, “Untitled Film Stills,” 1977–1980

This project made Sherman’s the face that launched a thousand theories. She removed the text from conceptual art and made the image personal and impersonal at the same time, presenting herself as everywoman and no woman. That, and she was a New York woman who was unafraid to enjoy clothes and makeup. (See Q&A, here.)

KEITH HARING, Untitled, EARLY EIGHTIES

For a few years, the Haring image known as the Radiant Child was everywhere downtown; there was one in my hallway, but an ex-girlfriend cut it out and took it after we had a fight. Haring served as a friendly face to the club-kid East Village art pack. That scene ran hot and burned out young; so did Haring, who died of AIDS at 31, in 1990.

DAVID HAMMONS, BLIZ-AARD-BALL SALE, 1983

Hammons set up shop and sold snowballs next to the vendors on Astor Place. It was just one of the complex ways in which he’d bring Duchamp’s gestures out of the gallery and onto the streets.

THE ARGUMENT STARTER

ANDY WARHOL , SELF-PORTRAIT, 1986

Many say that after Andy Warhol was shot in 1968, his work fell off. Yet Self-Portrait, one of the last paintings he made before he died in 1987, is a retinal powerhouse. Before Warhol, the Day-Glo palette didn’t exist; now it’s ubiquitous. The off-register silk screens make his image seem to move. Warhol is the Ur–New York artist, the hipster and the pitchman, a swishy genie-warlock-Buddha; there’s a little of Andy in every breath we take.

ANDRES SERRANO, PISS CHRIST (IMMERSIONS),1987

Piss Christ was attacked in the U.S. Senate; the following year, the Corcoran Gallery canceled its Robert Mapplethorpe exhibition. It was New York versus America, and it’s still not clear who won. When government funding dried up, institutions started ceding power to rich patrons—and grew dependent on their whims.

CADY NOLAND, SOLO DEBUT AT AMERICAN FINE ARTS, 1989

Much of the found and altered material, deployed seemingly willy-nilly, that fills galleries today owes its existence to Noland’s “scatter art”, made up of scraps of the city by way of the Marquis de Sade. Her art reified New York’s relationship to metal, mayhem, and advertising run amok.

JEFF KOONS, DIRTY—JEFF ON TOP, 1991

Koons’s “Made in Heaven” show depicted him having sex, over and over, with his porn-star wife. Perhaps spooked by the culture wars, the art world rejected him, saying he’d gone too far—in the process playing into his hands. He’s the straight Andy Warhol.

KARA WALKER, GONE, AN HISTORICAL ROMANCE OF A CIVIL WAR …, 1994

In hair-raising silhouettes depicting characters from the antebellum South killing and having sex with one another, Walker tore the scab off the history of race. Her art is like a ride on the No. 6 train to the Bronx—if, instead of ignoring each other, we all erupted into mayhem. Hers is the id that’s always right below New York’s surface.