Around the time New York began life, Mayor Lindsay was encouraging Hollywood to consider the city as an exciting place to shoot. Boy, was it. The cameras arrived in an era of racial unrest, filth, and crime, and the world discovered what it was missing—for better and worse. You’ll notice that many of the movies here come from that decade. That was not by design. But if you’re looking for films that capture something emblematic about New York, it’s hard to leave out The French Connection, Taxi Driver, or Annie Hall. It’s hard to leave out Death Wish, too, even if it’s hateful. What’s had that kind of cultural impact recently? I Am Legend? If you’re upset that something you love isn’t on this list, well, so am I. And I know there are too few films directed by women—a situation that should change in the next 40 years. But what follows will conjure up New York, in all its splendor and tumult.

PLANET OF THE APES, 1968

No, it wasn’t shot in New York, but that devastating final image of the Statue of Liberty jutting out of the sand implied that the preceding ape-stravaganza had taken place in—Hoboken? The Bronx? Scarsdale? Was it a harbinger of the anarchy to come? Hell of a time to launch a magazine.

ROSEMARY’S BABY, 1968

Roman Polanski brought his gargoyle wit to Ira Levin’s sick-joke novel (right on the feminist-misogynist border) about a waifish wife (Mia Farrow) whose husband (John Cassavetes) gets a Broadway hit in return for letting Satan knock her up. Polanski changed how we thought about women’s control over their bodies—and our neighbors in New York apartment buildings.

MIDNIGHT COWBOY, 1969

Everybody was talkin’ at Jon Voight, especially Dustin Hoffman’s scuzzy Ratso Rizzo, in John Schlesinger’s Oscar winner, which dramatized how New York turns nice Texas boys into prostitutes and killers. But oh, the people you meet!

HOSPITAL, 1970

In this wrenching vérité documentary, Frederick Wiseman captured the plight of sick poor people in an era of crumbling city services. It was at once ultrareal and a metaphor for urban indignity.

EL TOPO, 1970

At 12 a.m., Alejandro Jodorowsky’s splattery, nihilist Mexican Western packed the Elgin and became the first “midnight movie.” Later, audiences fell hard for The Harder They Come, gagged as one when Divine devoured a fresh doggy turd in Pink Flamingos, and shrieked back at The Rocky Horror Picture Show. Anything that flopped with the staid and the straight had a shot at keeping the city that never sleeps awake.

SHAFT, 1971

The uptown audience had never seen anything like this action hero who mocked whitey’s law, screwed (and threw away) whitey’s women, and exulted in his own potency.

THE FRENCH CONNECTION, 1971

Pauline Kael wrote that on-location shooting had ushered in a new age of “nightmare realism,” with New York as “Horror City.” Here was Exhibit A: trash, horns, gore, Gene Hackman’s Popeye Doyle slapping suspects around, and a chase scene yet to be equaled for suspense and public endangerment.

DEEP THROAT, 1972

It was shot in Florida, but Linda Lovelace’s talent captured New York’s imagination. Everyone—the raincoat crowd, the intelligentsia, the middle-class-curious-yellow—wanted to see the first hetero porn film with blow jobs. The prosecutor who sued to close the theater (he won) seemed most alarmed by the suggestion that it was “normal to have a clitoral orgasm.”

MEAN STREETS, 1973

Martin Scorsese grew up in Little Italy, studied at NYU, and crafted a feverishly expressionistic portrait of small-time hoods and neighbors that felt so rich, so rooted, that audiences took it for realism. A New York film style was born—and so were the careers of Harvey Keitel and the phenom that was Robert De Niro.

DEATH WISH, 1974

The urban-vigilante template. Bernie Goetz came a decade later; the rest of the crowd lived vicariously and learned to love the death penalty.

THE GODFATHER PART II, 1974

The first part was a better piece of storytelling, but Francis Coppola’s follow-up enlarged our understanding of the immigrant experience, from Ellis Island to Little Italy to the ’burbs to Lake Tahoe, as a vibrant sense of community gave way to chilly isolation. Are there many sequences greater than the rooftop trek of De Niro’s avenging Vito Corleone above the Festival of San Gennaro?

DOG DAY AFTERNOON, 1975

Al Pacino robs a bank to fund a sex-change operation for his lover, and all hell breaks loose—“all hell” meaning “New York squared.” As Pacino madly fires up the crowds (“Attica! Attica!”), we get a concentrated dose of what drives so many New Yorkers: enraged entitlement, a wide streak of exhibitionism, and a nagging sense that all will not end well.

TAXI DRIVER, 1976

Death Wish inside out, with the psycho innards exposed. Paul Schrader wrote a Dostoyevskian odyssey based on nights prowling the Deuce, and Scorsese and De Niro transformed it into a hallucinatory expression of urban alienation—of “morbid self-attention” and rage in search of release. “Everybody’s talkin’ at me” was now, “You talkin’ to me?”—Blam!

NETWORK, 1976

New York in the seventies was the perfect setting for ex–TV writer Paddy Chayefsky’s anti-television broadside, which anticipated ugly-spirited reality shows and their soulless producers (embodied by Faye Dunaway and her cheekbones). Audiences mimicked unhinged newsman Howard Beale (Peter Finch) and screamed, “I’m mad as hell, and I’m not gonna take it anymore!” Purged, they take it still.

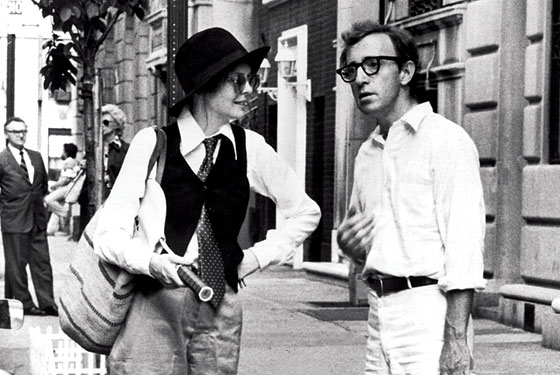

ANNIE HALL, 1977

Many films of Woody Allen—a symbol of New York’s Jewish heritage whether he likes it or not—could have been here, but this was the one that made so many of us so happy, certain that even if we didn’t end up with the girl or guy of our dreams we could still celebrate our inner fools. The films to come would be tonier (Manhattan), more thrillingly fanciful (The Purple Rose of Cairo), and more scorching (Husbands and Wives). But for daft pleasure, the courtship of Woody and Diane has few peers.

SATURDAY NIGHT FEVER, 1977

It began with Nik Cohn’s, uh, fanciful article in this magazine, but the fib—and John Travolta’s cock-of-the-walk moves, and the Bee Gees—fueled the movement. Suddenly, Bay Ridge swarmed with pomaded Italian guys who would soon find themselves aligned with the Village People.

AN UNMARRIED WOMAN, 1978

Michael Murphy told Jill Clayburgh he was leaving her for a Bloomingdale’s salesgirl and she threw up. She got her own back—plus Soho boho Alan Bates. But Kramer vs. Kramer (1979) took the dad’s side against moms who leave their kids to find themselves (if they ever existed). Meryl—in her movie breakthrough—sold it.

ALL THAT JAZZ, 1979

Broadway and film treasure Bob Fosse fashioned his own relentless, amphetamine-like syntax to rat-a-tat-tap out his own epitaph—his death onscreen (and, one suspects, in life) a consequence of said relentlessness and amphetamines.

MY DINNER WITH ANDRE, 1981

Wallace Shawn and Andre Gregory proved good talk wasn’t cheap.

SMITHEREENS, 1982

The selfish opportunistic club girl gets what’s coming to her, a vision candy-coated in Susan Seidelman’s next East Village–set movie, Desperately Seeking Susan—which fostered the illusion that Madonna had screen presence.

TOOTSIE, 1982

A pain-in-the-ass New York Method actor (Dustin Hoffman) finds his inner female powerhouse. Worth every bit of the tsuris that went into making it.

WILD STYLE, 1983

The seminal hip-hop D.J. break-dance graffiti doc that gave those subway squiggles an irresistible backstory (and backbeat).

THE BROTHER FROM ANOTHER PLANET, 1984

An ingenious John Sayles premise: the black alien who merges with the underclass—and is even more alienated.

STRANGER THAN PARADISE, 1984

Jim Jarmusch proved that minimalist form plus minimalist content could add up to a maximalist artistic statement of anomie, East Village style.

PARTING GLANCES, 1986

An indie gay (AIDS-oriented) feature that inspired a new breed of filmmakers (the ones that survived, anyway).

SUPERSTAR: THE KAREN CARPENTER STORY, 1987

The only movie here you can’t officially see (song rights pointedly withheld). But Todd Haynes’s Barbie-doll weeper made this New York–based gay deconstructive ironist a legend.

WALL STREET, 1987

In the age of Milken and Boesky, right and wrong dueled it out in the head of stockbroker Charlie Sheen—except lefty melodramatist Oliver Stone gave the good lines to the devil, Gordon Gekko (Michael Douglas). Generations of greedheads had a brand-new role model.

FATAL ATTRACTION, 1987

Suburban married man Michael Douglas fucks Glenn Close in the inferno that is the meatpacking district, thus bringing about the stewing of his child’s pet rabbit and the invasion of his (no-place-like) home. After cheering her bloody demise, couples argued over which was more dangerous, AIDS or indignant feminists.

THE ARGUMENT STARTER

SEX, LIES, AND VIDEOTAPE, 1989

The film itself has zero connection to New York, but New Yorker Harvey Weinstein was nearly laughed out of Sundance for paying $1.1 million to acquire it, and when it broke through commercially, it changed the fortunes of Miramax, lower Manhattan (as a production-distribution powerhouse), and American indie cinema forever. And New York had a new King Kong.

DO THE RIGHT THING, 1989

The hopped-up She’s Gotta Have It (1986) was Spike Lee’s ticket to celebrity. But this “joint” was his swing at the moon. Evenhanded? Nah: Malcolm X trumped Martin Luther King. Noisy whites feared it would inspire copycat vandalism. Instead, it helped Dinkins vanquish Koch. Lee was triumphant. (See Q&A, here.)

KIDS, 1995

Larry Clark’s kids weren’t all right: They hung around Washington Square Park doing drugs and having sex and getting AIDS.

GIRLFIGHT, 2000

Karyn Kusama’s you-go-girl Rocky, with Michelle Rodriguez as a pisser who boxes her way out of the male-dominated projects, busting noses and egos.

25TH HOUR, 2002

Spike Lee added a post-9/11 backdrop to the existing script of a drug dealer (Edward Norton) having a last look around before prison. Did that addition work? It’s debatable. But the hero’s dazed mournfulness captured the city’s mood.

UNITED 93, 2006

Too soon to dramatize 9/11? Maybe not soon enough. It was as much journalism as art—perhaps a rough draft for the 9/11 New York works of art to come.