Last November, it was Thanksgiving break. This February, a funeral. In April, a bachelor party. And in May, a wedding. At these moments, we come together. And eventually, out of nowhere, it starts to come out of our mouths. A long talk, a wild night, a tough phone call, and then “I love you, man.”

It’s not the “love” itself that hits hard — that’s always been there. It’s what’s implied after that loving declaration. It doesn’t have to be said; you can feel it.

“I love you, man [for sticking with me].”

“I love you, man [for not disappearing on me when I fell off the grid for a year or so].”

“I love you, man [because sometimes I’m the worst].”

“I love you, man [for keeping me alive].”

“I love you, man [for reminding me how to be good].”

“I love you, man [for proving to me that it’ll be all right].”

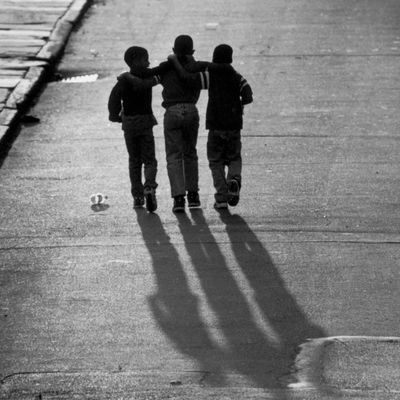

There’s a group of men I’ve known since we were children. Some fell into my life as early as the single digits, all before high school began. Growing up in Atlanta, these boys became my first inner circle, before I knew what that meant. Each of us had our own outlier friends, and different factions and smaller crews would break off, depending on the activity, the neighborhood you lived in, the sports you played, and, as we got older, the trouble you liked to get into. There was never a declaration of who was in the circle, or that there was even a circle. But it was obvious which boys continued to find ways to cross each other’s path or collect stories with one another.

In no way was I the sun around which this collection of boys revolved. Quite the contrary, I was more of a floater within the group, for years the one without a clear best friend, a trait that would prove contagious. As time went on, the whole proved more necessary than any single part.

I once wondered if my insular circle of boys would be my undoing — perhaps all of ours. I mean, teenage boys are in a constant state of trying to derail their futures, and occasionally end their lives. And these odds only increase with each additional teenage boy you add to the mix. We never would have been characterized as a dangerous bunch; it’s just that the feeling of invincibility that comes from going to school in a remarkably nurturing bubble, combined with living in the middle of a city that routinely popped said bubble, meant we were always two decisions away from something really bad happening.

Our high school, college, and early adult years were not perfectly synced. We experienced things, went through rough patches, and had breakthrough moments of true happiness at different times — all while moving apart and growing apart. In college, we would come home for holidays and pick up where we left off, and we felt as if we would always be able to do that. But our brief reconnections were happening in the shadow of extreme, rapid personal independence — each of us was creating a personality beyond the group. We started showing signs of having different ideas of what was fun. And then, one by one, people started considering falling in love. At that moment, after dedicating two-thirds of our lives to the feelings, opinions, stories, and whereabouts of one another, it looked as if it was all over.

This fear was initially pinned to the sudden appearance of significant others, but that was a smokescreen. What really happened was everyone was in various stages of experimenting with being a subpar man. Being a shitty guy has a way of warping the understanding of what it means to be manly. As in, the worse you are — rude, dishonest, uncaring, downright scoundrelly — the more of a real man you are. Our friendship had been the reason we’d been able to get back up when we fell, stay afloat, even to learn how to grow up, for so many years. But here, both geographically and figuratively, separation within the group was at its high point, communication at an all-time low. No one seemed to trust themselves in relationships, and for good reason. You begin to feel like an impostor when people know you, but only the good side of you. We were designated as “good guys,” but we were no longer as good as it seemed. There’s an extent to which you know your leash is longer, that more chances are available, less trouble awaits you, when people think you’re one of the good ones.

The bad began as an act, but was ripe for becoming a reality. But it wasn’t real, and slowly, one by one, people found ways to break the trend. The task was recapturing that initial positivity, that potential — the aspect of ourselves that truly came out in each person when we were all together, caring for each other, and keeping each other in line.

As often happens, it was the milestones that started to bring us back together. In 2013, one of the guys in the group’s father died. People dropped whatever they could to support him, because, for some of us, he was our father, too. It was a reminder that when one grieves, we all grieve. And now, when one of us finds that maybe forever person, we all fall in love, and we help our friend stay in love and not fuck up that love. We’re all taking cues from each other — everyone advanced in different ways, struggling in others — in this hunt to finally be great men. We need to stick together, because when one person figures something out, it’s contagious.

Though we never said it growing up, we always knew how to love each other. And now, at different speeds, we’re learning how to love ourselves. And then love others. And tell other people we love them. And actually mean it.

It feels good to be in a group that shared beds with each other years ago out of necessity, and still will on occasion out of camaraderie. It’s fun to be among the people who speak exactly your shorthand, for whom the same random thing sends you into a nostalgic spiral of inside jokes, throwback references, and obscure rap lyrics (though we have gotten slightly better at including others in our mania). And it’s a godsend to look for guidance from people who have figured it out, when you’re the one in the group with the most to still figure out about being a good man.

At a recent bachelor party, once an inner-circle quorum had been reached, we started into one of our late-night “How are you really?” conversations. About ten minutes in, however, I went looking to round up a few more of our crew, partly because I wanted them to know how I was really doing, but also because there’s never just one of us going through something. I almost felt selfish having a soul-baring conversation in one of our reunion sessions without everyone present.

Sometimes, no one wants to be the one to break the seal of small talk. But increasingly, it’s become clear that there’s no place more comfortable to go there than among this group. And once one of us goes there, everyone’s ready for their turn. The snowball of admissions, the recognition of shared experience even though we are now such different people.

It’s fun, it’s silly, it’s increasingly intense and honest, and then it’s over. That Real World–esque moment takes place when everyone has to leave the house after a weekend and go back to their lives, walking away from this collection of friendship that we’ve all grown to learn is rare. There’s always someone who has the early Sunday morning flight and has to tap out late Saturday night, causing a flurry of tight hugs, quick one-on-one talks, and promises that get less and less empty over time. The succession of good-byes continues, one after another, until everyone is gone. Each good-bye is unique, because each boy has given me something unique, even though the words are still the same.

“I love you, man [for showing me how you’re supposed to risk it all for someone].”

“I love you, man [for showing me that having someone means more than having things].”

“I love you, man [for showing me how to not care what the world thinks].”

“I love you, man [for showing me how to change, while still being yourself].”

“I love you, man [for showing me that nothing will be better than loving something hard — nothing].”

We pushed through a rough patch, and now we’re back on the same team. There’s a lot of love among us, and it’s no longer just insular. This is not just the camaraderie of nostalgia and convenience, but true friendship, where love is helping those you love learn how to love.