F or a laugh, Google “Y2K panic.” It all seems so innocent now—really, anything before 9/11 seems like it happened a very long time ago. There was the Ohio family, chronicled in Time magazine in 1999, that had stored away a couple of rifles, a shotgun, and a handgun. Mom was learning basic dentistry and field medicine … just in case. Dad was shutting off the power to see how many appliances could run on a portable generator. Then, in the early days of the World Wide Web, even postapocalyptic prophecies seemed more innocent. Tim LaHaye, who, along with a former sportswriter named Jerry Jenkins, was selling millions of copies of the Left Behind novels, which predicted a cataclysmic Second Coming, warned that Y2K could “very well trigger a financial meltdown, leading to an international depression, which would make it possible for the Antichrist or his emissaries to establish a one-world currency or a one-world economic system, which will dominate the world commercially until it is destroyed.”

Rationalists like us laughed at all this, and of course the world didn’t end. But now it’s ten years later, and we’ve had to tolerate the Bush presidency—born amid what was essentially a Supreme Court coup—9/11, the Iraq War, global jihad, the collapse (almost but not quite, but maybe still) of the global financial system (thanks, Dubai!), states dancing dangerously close to bankruptcy, and an ongoing global quasi depression whose ramifications we’re only now starting to glean. Even if you don’t believe Lloyd Blankfein is the Antichrist presaged in the Left Behind books, it’s hard to argue that there wasn’t at least some animating folk wisdom to the Y2K panic.

Y2K may not literally have happened, but the fear that underlay the panic—that of a dangerously matrixed, overleveraged world, open to massive self-compounding error, vulnerable to manipulation by unseen forces—seems, given recent events, to be pretty spot-on. Most important, the nagging sense that the agents of chaos are now so diffuse and powerful that no central authority can counteract them is no longer something just kooks believe.

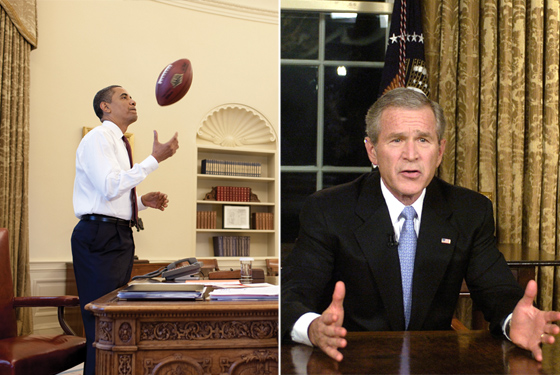

The aughts were one of those decades that will be looked back on as transformational. Considered metaphorically, it was a big-bang decade; the center exploded (literally), shooting power, opportunity, and status to the margins, culturally, geographically, financially. Most of the promise, and peril, of the digital revolution, despite the naysaying in the wake of the 2000 dot-com bust, proved true by 2009, creating huge opportunities for people (mostly younger) who understood the potential of subcontracting their lives to the digital cloud and beginning to disenfranchise people (mostly older) who persisted in analog. In a decade when institutions failed us one after the other—Bush was arguably the worst president in history; Wall Street was revealed (again) largely as a semi-legal cabal—opportunities went to the self-reliant, the self-starters, the hustlers. Whether we wanted to, or had to, we all become “brands of one.”

Like a movie that doesn’t show you the monster until the last 30 minutes, the aughts kept the leviathan hidden until almost the end. Despite 9/11, despite the dot-com crash, despite Iraq, life in the aughts was pretty swinging, even in (or especially in) New York, which fully shed the baggage of urban fear that dogged it well into the nineties. Murder rates continued to drop as Harlem and even parts of the Bronx became gentrified. Restaurants grew glammier and ever more overproduced. The meatpacking district, a place where people used to get rolled by transvestite hookers on their way to Florent, made the world a safe place for hordes of international douchenozzles (indeed, the word douche came back into vogue, probably as a result of the proliferation of hellish clubs here and in the West Twenties, which filled the city with all manner of nightlife detritus). Wall Street players and hedge-funders splashed mad cash on bottle service before taking the after-party back to their ever more excessively outfitted eight-figure pads. Meanwhile, smug Brooklynites of a certain age turned a once down-at-the-heels borough into a stroller-jammed bobo paradise as Brooklynites of a certain other age grew significant facial hair and pursued parent-supported lifestyles in Williamsburg, Greenpoint, and once-blighted Bushwick, creating art installations, digital mix tapes, and ostentatiously handcrafted somethings that they put up for sale on Etsy. For all of us, it felt a bit like a fool’s paradise, and that in the end is what it turned out to be.

Elsewhere in the country, this paradise never really achieved full flower, and the aughts’ rapidly metastasizing cultural and economic order hit home much earlier. Those feeling left behind manifested their fear in increasingly noisy paranoia. Movement Republicans and conservative Christians were uncannily early in channeling this new undercurrent of fear. Their ping-ponging fifth-column attacks—Fox News to Drudge to Breitbart, drawing on daily talking points from the “GOP Theme Team”—on mainstream-media institutions like the New York Times and network news, combined with the Bush administration’s contempt for “reality-based” analyses of world politics (to use an unnamed presidential senior adviser’s deathless 2004 coinage), were almost Stanley Fish–ian in their postmodern sophistication: The attacks were never on the facts. The attacks were on the idea of truth itself. Truthiness was Stephen Colbert’s word of the day on his debut broadcast in October 2005, at the height of Bush insanity. “Fair & Balanced”—Fox News’s tagline—was another brilliant joke. Only enraged liberals didn’t see the humor. Of course Fox News was not fair and balanced. But the subtext of the joke was: What is? The “truther” movement argued that the real story behind 9/11 was being hidden from the public. A 2006 Zogby poll found that 42 percent of those polled believed the 9/11 Commission was covering something up. Sarah Palin’s 2008 vice-presidential candidacy was not so much filled with lies—all politicians lie. It lived in a separate universe of meaning (post-truth?) inhabited by voters who believed that facts, at least those recognized by the Establishment, were hopelessly compromised.

In place of the culture wars of the nineties, the aughts saw a series of skirmishes between fact- and faith-based understandings of reality. The wave of schools discarding Darwinism for “intelligent design” reached a high-water mark mid-decade, before a federal judge ruled in late 2005 that a school system in Dover, Pennsylvania, which had adopted a curriculum taking “a more balanced approach to teaching evolution,” was acting unconstitutionally. Pennsylvania’s Republican senator Rick Santorum, who had previously supported the Dover school district’s decision to teach the “controversy of evolution,” quickly adjusting his stance Bill Clinton style before being handily bundled off the stage by Bob Casey (59 to 41 percent) the next year. Even so, then-candidate Barack Obama felt the need during the 2008 campaign to address intelligent design, and the need to trust “worldly knowledge and science.” It seemed brave, somehow, but the Obama ascendancy, at least for a moment, had appeared to mark a return to reality-based discourse.

But the center here as elsewhere could not hold. As the Obama administration sagged from dreamy possibility to dreary reality, and unemployment ticked past 10 percent, the ostensibly spontaneous “tea parties” and the borderline-menacing attacks on politicians who advocated the “public option” for health care began seeming less like wingnuttery and more like standard operating procedure in a media age that lacks a central authority to referee reality. The “birther” movement, with its obvious parallels to the truthers, continued through 2009 to insist that Obama was not a natural-born American citizen, undeterred by abundant evidence to the contrary. The birthers clearly weren’t operating in a vacuum. A July poll showing only 42 percent of Republicans believed the president was born in the United States would have been suspect, being that it was commissioned by the Daily Kos, except that other polls showed the same.

In place of the culture wars of the nineties, the aughts saw a series of skirmishes between fact- and faith-based understandings of reality.

The hopped-up controversy dovetailed nicely for the anti-immigration Lou Dobbs. He stoked the flames nightly, adopting his own brand of “fair and balanced” reverse constructions to continue to simply “ask questions” about Obama’s status. Now, freed from the nominal constraints of his CNN bosses, Dobbs is likely to become even more alarming, inching ever closer to Father Coughlin territory. So is the ever loopier and more popular Glenn Beck, a bipolar Howard Beale who is making vague and threatening noises about unleashing his foot soldiers on … whom exactly? Clearly, Palin wasn’t the only one going rogue.

Certainly, establishment players in New York, Los Angeles, and D.C. were providing the populists plenty of fodder. Formerly old-reliable Wall Street firms, stretched to keep up with upstart hedge funds that bet the deregulated casino economy, overpaid key players so much that the institutions ultimately seemed subservient to their star employees. Even as Citigroup flirted with bankruptcy earlier this year, star energy trader Andrew Hall, whose secretive unit was run from his farm in Connecticut, insisted he receive the $100 million in income he was contractually owed. And when Lehman Brothers went under in 2008 and giant firms like AIG were bailed out by the federal government, individual investors made billions shorting the financial meltdown. Contrarian hedge-funder John Paulson famously netted $15 billion betting against the British banking system and the U.S. real-estate market. When brands of one were outmaneuvering bigger, slower institutions, who needed institutions?

“We are all corner hustlers in a new economic environment,” Robert Greene writes in his new best-selling book with 50 Cent, The 50th Law, which extols an ethic of hyper-self-reliance and an abhorrence of all authority. Greene, a bookish 50-year-old onetime freelance writer, emerged on the scene at the start of the decade when his book, The 48 Laws of Power, became an Ur-text for aughts hip-hop and for hustlers everywhere. The 48 Laws, which sold hundreds of thousands of copies virtually, without mainstream notice, anticipated not only the coming economic chaos but also the opportunities that would be thrown up by the digital revolution. Self-reliance and free-form opportunism were in, credentialism and old-fashioned ladder-climbing out.

The major spoils of the new digital economy went largely to self-starting individuals, even if they were often funded by the well-established venture funds lining Sand Hill Road. Mark Zuckerberg, the 25-year-old founder of Facebook, may have gone to Harvard, but Harvard certainly didn’t teach him the hustle needed to outsmart his classmates, some of whom later accused him of stealing their idea for a business now said to be worth $10 billion. That neither Facebook nor Twitter may be real businesses is beside the point. The hustlers keep coming from places you least expect, upsetting and disintermediating whatever came before: MySpace trumped Friendster, Facebook trumped MySpace, Twitter may trump Facebook, something will trump Twitter, which after all is just a fresh way of distributing IMs. The apps revolutions unleashed first by Facebook and then by Apple’s decision to open-source much of their iPhone code, created millions of new entrepreneurs and entire new industries. As has the boom in virtual currency. They are cause and symptom of an ever-widening and faster-spinning gyre.

Indeed, PLUs (I’m projecting a bit here) became increasingly maladaptive to the new hustler economy. Eighties college graduates like myself jockeyed for jobs at once irreducibly blue-chip institutions like Goldman Sachs, Bain & Company, The Wall Street Journal, Condé Nast, and Cravath, Swaine & Moore. Some of us now sit atop shaky edifices, still smartly compensated but hardly sitting pretty. Others have been forced into shotgun midlife career changes. In our darker moments, we imagine ourselves like John Cusack in 2012, running to catch a plane piloted by a guy who can’t really fly as the ground gives way beneath our feet. It would be hard to imagine a current college graduate dreaming of a career in any of those corporations (perhaps excepting Goldman), spending twenty years brown-nosing and overworking his way to a partnership or tenure with its perks of a Town Car, $38 steamed halibut at Michael’s, and a life of suburban ease in Greenwich. Not only has the cheese been moved, to borrow from the title of the 1998 motivational best seller, but now, we know, we’re going to have to make the cheese from scratch.

T he digital revolution, the outlines of which were in place in 2000, has made the shift from credentialism to hustlerism permanent by wiping out gatekeepers in everything from media to investment to marketing and sales. Ever-increasing bandwidth and mobile computing brought us tantalizingly close to a world of infinite, instantaneous communications. Those who saw this coming convergence at the start of the decade were the winners. Those who didn’t were the losers.

In 2000, the record labels (losers) met secretly with a then-upstart digital music service called Napster—whom they were also suing—to negotiate a grand alliance. The discussion failed, somewhat predictably, and the lawsuit finally forced Napster to shut down in July 2001. Users promptly switched to the more sophisticated peer-to-peer-based Kazaa, launched only that spring by, among others, Niklas Zennström and Janus Friis (winners), who would later go on to disintermediate much of the long-distance-phone business with Skype. By October, Steve Jobs (big winner) introduced the iPod, paving the way for the end of the physical CD business. The top-selling record of 2000, No Strings Attached by *NSYNC, sold 9.93 million copies. The top-selling record this year, Taylor Swift’s Fearless, is likely to sell a quarter of that. As of this past June, with the closing of Virgin Megastore in Union Square, there is no major record-store chain in New York City.

Arrivistes proudly wore hooker heels as a sign of contempt for the old order. The point was to look like a hustler.

Across the mediascape, the story was similar: loserville, population increasing almost daily. Blockbuster, the dominant DVD-rental chain, is playing frantic catch-up to challenges by Netflix (founded in 1997) and Redbox (founded in 2002), both of whose business models it is trying to mimic. The independent-movie sector has been more or less decimated as funding for non-massive studio titles dries up. In October, Miramax, the iconic movie studio started by Bob and Harvey Weinstein before being sold to Disney, announced it would no longer operate as an independent entity. Nobody would be shocked if the Weinstein Company, the brothers’ new venture, followed suit. In TV, NBC gave up a prized chunk of TV real estate, the ten-o’clock hour, to Jay Leno, a necessary move but still humiliating for an iconic late-twentieth-century brand. In publishing, the Borders Group teeters at the brink of oblivion, surviving on a high-interest loan from a private-equity group. The print-newspaper business continues its double-digit year-over-year decline as the Washington Post decides to throw in the towel on national coverage. The online news business will prove no savior once Rupert Murdoch has his way and newspapers start charging for digital access. Opportunistic, less-capital-intensive entrepreneurs like Gawker’s Nick Denton, the Business Insider’s Henry Blodget (smartly re-branded after being barred from securities trading in 2003), Politico, and the eponymous Huffington Post stand poised to gobble up market share, and top talent, once the pay wall goes up.

If you weren’t trying to, you know, make a living at this stuff, the aughts were a time when everyone got to floss. Blogging preceded the browser, but it wasn’t until the last decade that it became democratized thanks to blogging tool kits like Blogger, which was later bought by Google, and LiveJournal (launched months apart in 1999). As late as 2003, there were fewer than one million blogs. Today there are over 100 million worldwide. YouTube (launched in 2005 and also later bought by Google) did the same for video, while Twitter (launched the next year and not yet bought by Google) brought us closer to that axiomatically impossible convergence point at which the number of content creators equals the number of consumers.

The geopolitical implications of this decentered, matrixed mediascape are only now starting to become clear. Al Qaeda, mimicking the tactics and shape of a social network, proved nearly impossible to counterterrorize despite all the talk in the Pentagon of a new kind of “asymmetric warfare.” Momentarily, thrillingly, social media seemed to sustain a democratic insurgency in Iran, though, truth be told, old-fashioned texting and the BBC’s Farsi service probably had just as much to do with it. Social networks fed the myth of Neda, the impossibly beautiful victim of a Basij-militia gunman. But the power of social media to disseminate information instantly, uncontrollably, globally, also showed its limits. In a feral age, shame is not a deterrent (maybe it never was), and widely dispersed non-terrorist movements have a hard time exerting nonvirtual pressure. The thoroughly discredited Iranian government, led by its truly scary president, continues on.

C ulturally, the breakdown of traditional financing models has been by turns exciting and distressing. The amount of music being created—and heard, albeit by more and more splintered audiences—is breathtaking. And because this music found us via blogs and social networks, rather than through traditional baksheesh-driven major-label marketing schemes, it felt more real, somehow. Indie rock and hip-hop returned to the garage; a lo-fi aesthetic became a symbol of authenticity. Thousands upon thousands of bands were able to reach loyal audiences, and make a middle-class living, by using social media and digital downloads. The freshest sounds belonged to Brooklyn bands like Matt & Kim, MGMT, and the rapper Kid Cudi, whose instantly canonical stoner anthem “Day ‘N’ Nite” sounds like it was produced in a narcotic haze in the then-23-year-old’s Brooklyn apartment. The song banged around the web for more than a year before it finally made it to MTV.

Rap always extolled the hustler life, but it was preppily clad Kanye West who mainstreamed it. His 2004 concept album, The College Dropout, started mad beef with, of all people, university-degree holders, as on “Graduation Day”: “You get the fuck off this campus / Mutha what you gone do now?” It was a touch harsh, but he wasn’t wrong to ask. The label system, meanwhile, launched fewer and fewer true pop stars. For every Lady Gaga there was a Justin Bieber, who essentially self-launched via YouTube and is now getting Debbie Gibson–level adulation at malls around America. Prepacked pop stars like Miley Cyrus and the Jonas Brothers were still big among the tween and teen set, but even they felt like a rearguard action.

Movies had a tougher time adapting, if only because the technology for video wasn’t quite as cheap yet as it is was for music. As a result, it was a relatively barren decade, compared with the indie-film boom of the nineties. The indie movement, lacking inspiration, became increasingly solipsistic, twee, ripe for parody. Studios bet big and won, mostly, on high-concept blockbusters like 2012 and the Spider-Man series, proving that there is still a place for mass culture. It was just not a very interesting place. But green shoots of hyper-low-cost film production, particularly the New York–based “mumblecore” movement (see Joe Swanberg’s talky Hannah Takes the Stairs), revealed the potential for exciting DIY filmmaking—as long as you don’t need to see shit get blown up. By late 2009, the $15,000 Paranormal Activity, which itself evoked the $60,000 Blair Witch Project at the decade’s beginning, broke $100 million in revenue, showing that the decline of fat-cat Hollywood is bad news mostly for … fat-cat Hollywood.

In TV, the decade’s biggest, and perhaps sole, truly mass cultural phenomenon itself drew on an open-source model. The American Idol format, which launched in the U.S. in 2002, brilliantly recast the decade’s governing tensions as pop culture. Simon Cowell played to perfection the Establishment pantomime villain (as the British like to say), brutally asserting his insider’s prerogatives as he put down or elevated his favorites. The savviest contestants, like wacky-haired Sanjaya Malakar, ignored Cowell and played to the crowd, which, of course, had the final word. The crowd, in turn, voted in numbers: 65 million votes for the 2004 finale. In TV, as elsewhere, the middle could not hold. Lowbrow and high(ish)brow thrived. HBO’s The Sopranos and The Wire, two of the decade’s best series, wove broad suburban and inner-city tapestries of life in the time of the hustler. Their anti-heroes killed without compunction, even as the camera prompted us not to judge them. It was just bizness. Mad Men’s Don Draper was Gatsby recast as a mid-century adman, working the ultimate hustle: His entire life was a lie. The women of Desperate Housewives waged psychological warfare on their neighbors against a setting of prefab pleasantness. Here, as elsewhere, the veneer of society was a very thin one.

Fashion, like TV, abandoned Establishment notions of taste, almost en masse. Designers had no choice. Consumers were increasingly ignoring traditional arbiters like women’s magazines and the trap of fashion cycles and seasons. Lucky magazine, founded in 2000, got everything right except the platform (it should’ve been a social network), providing options instead of issuing diktats. Forever 21 led the movement toward disposable clothing and made a mockery of spending $2,000 on an Ann Demeulemeester frock. Where money was being spent, it went for nose-thumbing nouveau richery: $3,000 Balenciaga handbags, diamond-studded cell phones, not to mention absurdly excessive bouts of obviously fake plastic surgery (the point was to look like you had very expensive work done, not to hide it). Flush with fast cash earned from real-estate speculation, cell-phone monopolies in sub-Saharan Africa, bank scams in Dubai, and insider deals with Vladimir Putin, new money flouted conventional taste by dressing itself up in Versace, Gucci (which Tom Ford brilliantly took from the boutiques to the streets; he famously touted his men’s cologne as smelling like the sweat off a man’s balls), Cavalli, Dolce & Gabbana, and reconstituted Pucci. Arrivistes who once used to launder their images through Calvin or Ralph now proudly wore hooker heels as a sign of contempt for the old order. Lower-middle-class kids, copping the “chav” look from the U.K., rocked Burberry plaid or spent hundreds on Ed Hardy, truly the most godawful fashion trend since Zubaz. The point was, you wanted to look like a pimp or a ho. You were a hustler.

I s all this good or bad? Depends where you sit. If you’re reading this magazine, meaning you’re capable of maintaining your concentration for more than 140 characters, it’s probably bad. But the world that took shape during the aughts is potentially a very exciting, democratic one. As recently as 1999, Nicholas Lemann could attack the Scholastic Aptitude Test as a tool used by the meritocracy to secure its status as a new oligarchy. That can no longer be a fear. The Internet has rather definitively leveled the playing field. This does not mean that everyone has an equal chance. But it means that the traditional perquisites of the Establishment to determine who is and isn’t let in no longer hold and aren’t really that interesting to boot. The fear now is that no one is in charge. That we are all adrift in a vast, roiling sea, the contours of which none of us can fully discern. What we do with that fear is up to us alone.