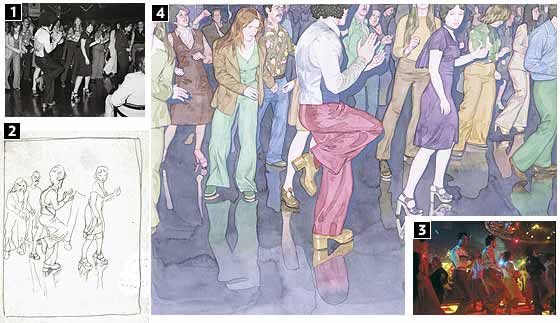

Though he wasn’t born until 1977, Tony Manero, the disco-dancing, white-suit-wearing, finger-pointing-to-the-sky hero of Saturday Night Fever, exists now as a mascot for “the seventies” in the way, say, that Gordon Gekko exists as a mascot for “the eighties,” or Mickey Mouse exists as a mascot for the wonderful world of Disney. So it’s easy to forget that Saturday Night Fever wasn’t all glitz and disco balls and stayin’ alive; it was a dark portrait of sexual aggression and suicide among working-class Italian kids stuck at the ass-end of seventies-era Brooklyn. That movie, in turn, owed its life to a portrait painted in a New York Magazine cover story, “Tribal Rites of the New Saturday Night,” that appeared 30 years ago this month—literal portraits, in fact, by illustrator James McMullan, whose work you see reprinted here. The article, written by Nik Cohn, about a group of Bay Ridge “Faces” who colonized a disco every Saturday night, turned out to be almost entirely made up—a combination of New Journalism extrapolating and deadline-pressure riffing. “At the time,” Cohn later wrote, “if cornered, I would doubtless have produced some high-flown waffle about Alternative Realities, tried to argue that writing didn’t have to be true to be, at some level, real. But, of course, I would have been full of it.”

McMullan’s paintings, however, were drawn closely from photos he took during multiple trips to the Bay Ridge disco called 2001 Odyssey—first with Cohn, then alone. The article was revealed to be fiction. The paintings are, in essence, fact.

“It was Milton Glaser’s [New York’s design director] idea that I could act like a visual journalist,” McMullan says now. “Instead of illustrating a story after it’s written, I’d be there in the beginning and develop my own story out of what I see.” What he saw was a world not of disco glitter but of melancholy yearning. The real 2001 “was like a tired old supper club,” he says, “that had quickly, but not entirely, been converted to a dance club.” (In the paintings, much of the club’s floor is covered by a dingy, rec-room-style carpet, so vividly captured you can practically smell it.) He used a flash for the photos, and “the flash revealed all this stuff that in the dim light you weren’t able to see. Particularly in the backgrounds. You saw people’s non-party faces, as it were.”

The paintings now stand as a kind of unofficial storyboard for the film: the real film, the gritty, vaguely hopeless one, not the smoke–and–Bee Gees cartoon that persists in memory. But Clay Felker, the magazine’s editor, was not impressed initially by McMullan’s work. “He said, ‘Jim, what kind of a story are you telling? Nothing’s happening here.’ Which was true, in a sense. No knife fights, no dramatic moments. Just people, in this situation.” Glaser, however, championed the paintings. “He took Clay aside,” says McMullan, “and he said, ‘Look. These are incredible. And once they run, everyone will understand.’ ”