A village of high-concept lean-tos is about to sprout in Union Square. The gathering of bulbous and bristling huts, variously built out of rattan, grass, wire, cardboard, hemp, and wooden slats, may resemble a camp for design-conscious refugees. In fact, it’s a group of avant-garde sukkahs, the devotional huts that observant Jews erect each fall in commemoration of the desert days, when their ancestors were homeless nomads. The word “sukkot” refers both to the huts (plural) and the holiday (when uppercased), an exuberant seven-day harvest festival, in which celebrants brandish citrus fruits called etrogs and palm, willow, and myrtle branches gathered into bundles called lulavs. Much everyday family life moves to rough-and-ready shacks, often festooned with edibles, in which to sing, eat copiously, and (weather permitting) sleep.

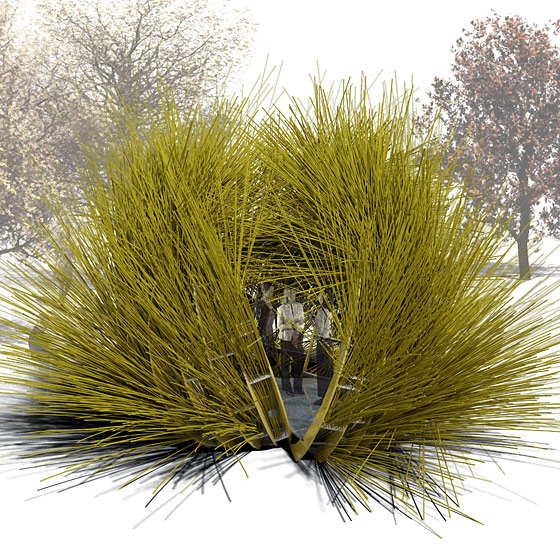

The design competition Sukkah City encouraged its entrants—all 600 of them, from 43 countries—to marry religious tradition with architectural radicalism in the timely form of short-term shelter. A jury chose twelve finalists, whose structures will stand in Union Square on September 19 and 20; by voting here, you, our readers, will choose the winner. It’ll be on view until October 2.

In a way, these interlopers should look familiar. In recent years, a scattered army of architects has tried to invent cheap, simple, and portable ways to house millions in a hurry. They have designed budget houses for hurricane victims, cabins made of paper tubes, refugee tents, tsunami shelters, mobile homes, habitable shipping containers, polyester yurts, and so on. Temporary architecture also has its high-art counterparts, such as the Starn twins’ Big Bambú, a gloriously rickety castle of cane stalks lashed together atop the Metropolitan Museum, and SO-IL’s pole-and-mesh installation that’s on view through September 30 in the courtyard of P.S. 1.

Unlike more practical or whimsical instances of pop-up construction, the sukkah functions as concrete, if multivalent, symbol. It can be an expression of empathy with the homeless, which is why Ronald Rael and Virginia San Fratello fashioned a hut from hundreds of cardboard signs bought from the indigent. It can also become a semi-sanctum, an outpost of antiquity in the hectic present. Peter Sagar captures that mixture of separateness and participation in his entry, Time/Timeless, in which a hemp-fiber scrim turns the world outside into a shadow play. Henry Grosman and Babak Bryan’s Fractured Bubble, a wooden globe shaggily clad in native city grasses, interprets the sukkah as an urban civilization’s nod toward nature and the autumn harvest. These assorted meanings do not compete or exclude one another; ambiguity is part of the tradition.

So, too, is a thicket of rules. The Talmud demands that a sukkah have at least two and a half walls, a roof that allows indwellers to see the stars and feel the rain but nevertheless stay mostly in the shade. The roof must be made of uprooted organic material—twigs or fronds, say—but no food or utensils (no chopstick thatching allowed). Mystifyingly, the rabbis of yore explicitly permitted the carcass of an elephant to be used as one of the walls. (No contestants took advantage of that option, sensing perhaps that the Department of Buildings or peta might not concur.) Neither the DOB nor the Parks Department had a problem with Kyle May and Scott Abrahams’s proposal for a cedar trunk supported on glass walls. The competition’s rabbinic consultant worried that the log might be too solid, though, and required that it be perforated.

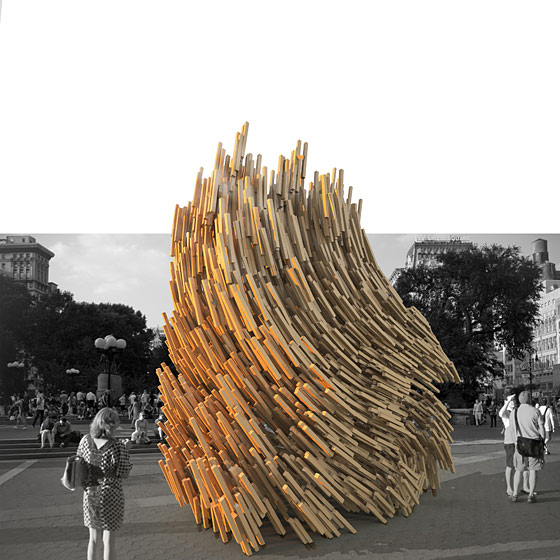

The best entries play on a childlike desire to duck inside a mini-structure in search of fantasy. The most alluringly over-the-top, Blo Puff, by the Brooklyn-based team called Bittertang, looks like some soft, curvaceous organism that encloses a walk-in pouch saturated with the smell of eucalyptus. The most theatrically intricate and least hutlike finalist is Repetition Meets Difference, by the German architect Matthias Karch. In this multilayered helix, lengths of wood are knotted together in a system of joinery that can make any structure infinitely extendable. As a secular urban pavilion it would be an ornament, but it is also a showy riff on a holiday about humility, a tour de force of engineering where none is needed.

At the other end of the complexity spectrum, the simple and lovely Shim Sukkah turns the most plebeian construction material—scrap-wood wedges used as spacers—into a permeable, poetic scrim. Creating something from nothing is a Divinity’s job; creating something great from very little is how thrifty architects earn their living. Gathering, by Dale Suttle, So Sugita, and Ginna Nguyen, finds a particularly delicate balance of poverty and loftiness by hinging together simple sticks in a wild, upswept assemblage that resembles that other great icon of the desert sojourn, a burning bush.

Anointing the winner of Sukkah City is almost superfluous; what matters is that for a short time, one of Manhattan’s few town greens will host a conclave of meaningful structures, created not as curiosities but as rest stops for the soul. This unprecedented event belongs in New York, and not just because it contains the largest Jewish community after Tel Aviv. This is a perpetually provisional city. New Yorkers live in too-small apartments they hope to trade in, cherish buildings that stand only until some developer decides to tear them down, and reform entire neighborhoods that reach a momentary sense of identity before changing again. Temporary, we get.

Shim Sukkah

tinder, tinker, Sagle, Idaho

On a contemporary job site, there is no more humble material than the wooden shim, used to fill gaps and level uneven surfaces. In this sukkah, the unassuming object becomes an essential building block, creating a unique atmospheric effect.

All renderings courtesy of Sukkah City

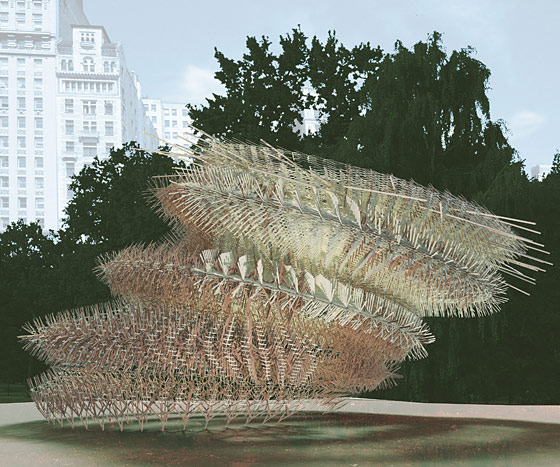

Blo Puff

Bittertang, Brooklyn

Blo Puff’s bloated body and furry innards acoustically, visually, and olfactorily separate the sukkah interior from the surrounding city. At night the sukkah’s glowing flesh alludes to the activities held within. Its crown, a ring of bamboo stakes held in place by inflated vinyl walls, holds a thick cylindrical mat of draped eucalyptus leaves that shade and perfume the interior. The sukkah is entered through a low opening on one side, which is obscured by a loosely draped interior lining of Spanish moss.

Fractured Bubble

Henry Grosman and Babak Bryan, Long Island City

“The sukkah is a bubble: ephemeral and transient,” say Bryan and Grosman. Emphasizing its impermanence, Fractured Bubble is made of simple materials: plywood, marsh grass, and twine. Its form is a sphere fractured into three sections. The schach is composed of phragmites, an invasive species of marsh grass harvested from Corona Park, Queens.

Gathering

Dale Suttle, So Sugita, and Ginna Nguyen, New York

This “calculated yet unpredictable structure,” in the words of its designers, is constructed from a nonlinear assemblage of wooden sticks that guide the eye toward the sky. “Whether wandering through the desert for 40 years or through the city for a day, all people desire respite. The sukkah is an icon for this relief from transience.”

In Tension

SO-IL, Brooklyn

In Tension is conceived as a simple parts kit, easily carried by a single person. The lightweight structure is held up by its own tautness, and the outer net creates a soft veil, transparent enough to be inclusive but dense enough to create a sense of being.

LOG

Kyle May and Scott Abrahams, New York

The sukkah’s overhead structure must be made of schach, botanical material removed from the ground. log inverts the typical lightweight structure, placing the foundation”a cedar trunk”atop laminated glass walls. Inside, one finds two simple gestures: a table and a candle, suspended from the roof. They’re positioned to create a zone of programmatic intensity within a poetic structure.

Sukkah of the Signs

Ronald Rael and Virginia San Fratello, Oakland, California

It is traditional to eat and sleep in the sukkah for one week each fall, as a way of practicing a kind of ceremonial homelessness and empathizing with those who don’t have a roof over their heads. As a political statement, and as a way of transferring the prize money to those in need, Sukkah of the Signs is clad with cardboard signs purchased from destitute individuals across the country.

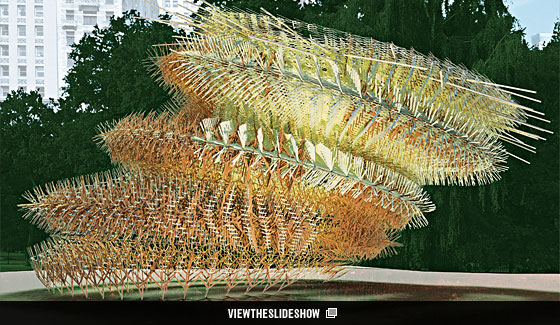

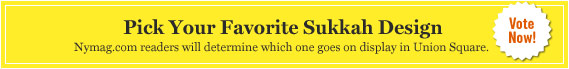

P.YGROS.C

THEVERYMANY, Brooklyn

P.YGROS.C, short for “Passive Hygroscopic Curls,” reinvents the common sukkah morphology using two overlapping layers of wood veneer. The lightweight, translucent structure absorbs humidity from the surrounding air. In humid weather, the wooden tips will bend up and twist into natural curly shapes, revealing their bright-green undersurface. When dry, they flatten back out.

Single Thread

Matter Practice, Brooklyn

This sukkah is constructed by threading a single wire around intersections of a temporary bamboo scaffold. Once the continuous wire is fully unspooled, the scaffolding is removed, leaving a rigid yet porous enclosure with a roof of dried flowers. After the holiday, the wire is wound back up, to be stored or transported to the next site. Each installation produces new kinks and bends in the wire, add texture.

Star Cocoon

Volkan Alkanoglu, Los Angeles, California

The sukkah is intended to be a meditative structure, a kind of cocoon in which personal transformation can take place. Of the many complex laws that govern its form, few are as detailed as the rules pertaining to the geometry of the shell. This curvaceous structure, designed with the Talmudic minimum of two and a half walls, is constructed entirely with bent cane tubes and rattan.

Time/Timeless

Peter Sagar, London, United Kingdom

This heavy timber structure, enveloped in a curtain of hessian, appears to float off the ground. According to Sagar, it “aims to achieve an awareness of time by removing the viewer from his surroundings and placing him into an environment in which he can only appreciate the passing of time by the changing of daylight and the eventual emergence of the night sky.”