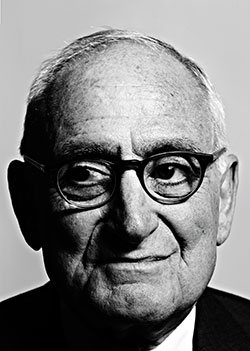

The architect Robert A.M. Stern occupies a physically impossible position in his profession. As the widely respected dean of the Yale School of Architecture, he sits atop an academic world that treats his buildings with condescension, which means that the people who look up to him also look down on him at the same time. A typical remark, from Alexander Gorlin, one of Stern’s former students and principal of his own firm: “A whole article just about Bob Stern? Does he merit that?” Stern has been called the Martha Stewart of architecture, a comparison suggesting that he’s selling a lifestyle rather than making art.

If you’ve ever walked by one of his New York buildings—and chances are you have; there are several dozen—it may have flitted across your consciousness like a pleasant memory, leaving a dusting of good feeling that’s hard to place. His architecture doesn’t evoke a wow so much as an mmm. Instead of indulging in outrageous height, bendy walls, or glittering façades, Stern beguiles with details: the interplay of pale limestone and black steel, a subtle setback toward the top of a tower, a pattern of bricks fanning out above a shallow arch. These brushstrokes accumulate into a patina of understated opulence—one that many architects find hopelessly passé. “Oh, he’s good with detail,” a colleague acknowledges in a tone that is meant to sound backhanded, sort of like saying that a novelist is adept at punctuation.

At 74, Stern has been batting away spitballs for decades, and he seems to enjoy the sport. As the architect of the George W. Bush Presidential Center, he earned the scorn of left-leaning colleagues who think nothing of working for repressive regimes in Asia and the Middle East. In the nineties, his association with the Walt Disney Company, including a master plan he co-developed for its built-from-scratch town of Celebration, Florida, triggered all sorts of jokes about Mickey Mouse architecture—until Frank Gehry completed Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, giving the brand a fresh reputation for adventure. High-modern snobbishness has ebbed a bit, but younger architects still pronounce his name with a hint of condescension, leaning slightly on those courtly middle initials, as if they stood for some obscure vice. (Actually, they stand for Arthur Morton.) Press them about what lies behind the smirk, though, and they start hedging furiously. No sooner have they finished accusing him of playing around with fusty classicism while the rest of the world has moved on than they realize that the austere glass box is just as archaic.

Compact, wiry, and Brooklyn-born, Stern is a cranky optimist with an acid wit. “My colleagues feel architecture should reflect the complexity of the world,” he says, his reedy voice buzzing with scorn. “And it’s always a negative complexity. I think you can celebrate a better world.”

You can tell something about an architecture firm’s aspirations by what the staff is wearing. Corporate firms like Skidmore, Owings & Merrill dress their architects like bankers; in the more cerebral and adventurous studios, scruffy junior associates could be mistaken for dog walkers. At Robert A.M. Stern Architects’ West 34th Street offices, the look is tailored and elegant. Some of the 285 employees evidently try to meet the boss’s sartorial standards, but he’s tough to compete with. On this day, he’s wearing a bespoke blue suit, chocolate-brown suede loafers, lemon-yellow socks, and a matching pocket square. He briskly leads the way up the stairs to his rooftop aerie, where he and his writing team have just produced Paradise Planned, a massive history of the garden suburb that comes out next month. It’s vintage Stern, contrarian and sweeping: At a time when it’s fashionable to give the suburbs up for dead, he puts out an exhaustive ode to the bucolic enclave. That has always been Stern’s strength. He’s so old-fashioned that he’s practically countercultural.

From the terrace of this peak-roofed penthouse retreat, Stern can survey the vast site of Hudson Yards, where he will almost surely be designing several residential buildings. He can also keep an eye on his High Line–hugging condo tower at 500 West 30th Street, which is under construction. His eye drifts to the new West Side, a crop of ungainly skyscrapers with delusions of sleekness. “They all want to be about the future, but of course they’re stuck in the moment,” he says.

Stern was an early adherent of postmodernism, which held that rather than attempting to invent an aesthetic from scratch, architects should dip back into the generous well of history. “The present, interacting with memories of the past, can create something that can be interesting in the future,” he recapitulates. This was an easily perverted idea. Some postmodernists, like Michael Graves, winkingly mashed up historical references and blew up pediments to cartoon proportions. Others hewed slavishly to Jeffersonian neoclassicism. Stern does something different: He adorns his buildings with the architectural equivalent of footnotes. The new library for the Bronx Community College cites Henri Labrouste’s Bibliothèque Ste.–Geneviève in Paris, the greatest of the big public research libraries, not just to flaunt a historical model but because Stern wanted students in the Bronx to bathe in Parisian grandeur. “If you walk into that library, and you think, This is what it’s like to be at Yale or at Harvard!, I think I’ve done something good for people. I’ve shown the respect of the body politic as a whole to their needs and their efforts to improve their lives.”

Stanford White designed that Bronx campus more than a century ago for NYU, and Stern has returned often to McKim, Mead & White’s moment, one of the last great flourishes of America’s neoclassical tradition before the advent of modernism. He is, in a sense, a 21st-century Stanford White, a traditionalist with a deep understanding of the contemporary metropolis (but without the sex-and-murder scandal). But Stern does not limit himself to graceful monuments. He has designed about 30 projects in New York, most of which stay politely in the back row of any architectural class portrait. One architect, when I mentioned Stern, asked, “Has he done many buildings in New York?” And then, as I listed them, said, “Oh, yes, of course. I know that one,” again and again.

At Yale, Stern has made the school a gathering point for practitioners of radically different persuasions, so it’s not as if he’s opposed to what he calls “me-too” architecture; it’s just that he’s appointed himself the profession’s chief defender of New York’s fragile fabric. While so much new residential architecture has been grinding away at New York’s texture, turning a stone city into a glass metropolis, Stern’s buildings exert a quiet friction against change—or at least against too much cheap change. He has helped shape the city’s constant self-reinvention by championing its glory days. His most famous work, the limestone palazzo at 15 Central Park West, hums with a revivalist Art Deco grandeur. His Superior Ink condominium at the far end of West 12th Street is New York’s handsomest newly built evocation of the industrial past. With its ample factorylike windows and ruddy brick facing and its row of townhouses (each one different) that peels away from the tower’s main bulk, Superior Ink is the kind of building you think you remember from a grittier time, only better. What might have been an ersatz knockoff is instead a thoroughly modern memory of a past that’s quickly being erased.

“My interest is not in being an autobiographical architect but a portraitist of places,” he says. “Other architects put the same building, more or less, in many different locations. And in this age of branding many people are reassured by that. But when clients come to us, they don’t know what the building is going to look like until we study the site and consult our library.”

Though he has worked all over the world, the subject that has absorbed Stern’s attentions most over the course of his career is New York. He and several associates have written a definitive five-volume history of its architecture, and he has learned to appreciate the city’s dense web of precedent, orneriness, and rules. Other architects may chafe at those restrictions; he finds them invigorating. Now he’s trying to export the wisdom they impose.

“There’s a New Yorkiness to our work,” he says, adding that Chinese clients arrive clamoring for it. “I know that, because those who have come to us want things like the buildings we had in the twenties and thirties—buildings that stepped back, that created skyline terraces and strong rooftop silhouettes, that had interesting rhythms of wall and window.” China’s cities have been developing at a frenzied pace, but they lack “the urban vitality that we have on virtually every street, even in the most remote parts of the city: a mixture of uses, a street that’s pedestrian-oriented, a street that encourages neighborliness among people, a street that is in itself a work of architecture. Our buildings try to enforce that model or develop it where it doesn’t exist.”

Peddling a canned version of New York–style urbanism to the Chinese, or designing a piece of deluxe chinoiserie, as he is doing for the Schwarzman College at Tsinghua University in Beijing—these are exactly the kind of practices that drive his high-minded colleagues crazy. “He has no problem thinking about architecture as a high-end service,” complains Amale Andraos, the founder, along with her husband, Dan Wood, of Work Architecture Company. The remark makes Stern’s practice sound vaguely sordid, and she goes on to explain that making the client happy is necessary but not sufficient. “Most architects have an agenda outside of the requirements of the client. That’s the ambition, anyway. If you think of Pritzker Prize winners, they’re supposed to have contributed something to the discipline by moving architecture forward or reinventing some aspect and by having the highest standards and being pure. So could Bob Stern win a Pritzker? Probably not.” Andraos may be right, but that tells you more about the Pritzker than it does about Stern.

To some extent, Stern courts the image of a man who spritzes himself in the morning with a little mist of nostalgia. He doesn’t use a computer (though, of course, his employees do). And he says things like, “You look at buildings now, and you can’t tell whether they’re residential or offices,” in the same tone that his parents might have used in the sixties, saying they couldn’t tell the boys from the girls. Wandering around the studio, I come across a shelf full of elaborately carved moldings—not the kind of samples you tend to see strewn around high-end Manhattan firms. Someone has sprayed the stylized foliage with gold paint, making it look like trim for a Caligula-themed hotel. “We don’t usually do gilt, but we have a Russian client,” an associate remarks.

Still, the picture of Stern as a servile purveyor of neoclassicism to the rich is a caricature. At a recent benefit for the nonprofit developer Common Ground, which builds housing for low-income residents, Stern accepted an award and wryly introduced himself by saying, “Most of you probably know me best as the architect of some of the least affordable homes in New York.” But as he points out in Paradise Planned, he was working on ideas for low-income housing in Brownsville as early as 1976. He has been involved in public planning long enough that no idea seems new to him: During the Lindsay administration, when he was a freshly minted graduate of Columbia and Yale, he was part of a group that advocated filling in some of the underused open space in New York’s housing projects with additional buildings—an idea that foundered, recently reappeared in a different guise, and has once again been shot down but that remains supremely rational.

More than a decade ago, he took over a program in which first-year graduate students at Yale help design single-family homes for low-income families in New Haven. More recently, his firm designed Cedarwoods, Common Ground’s 60-unit residential building in Willimantic, Connecticut. The income gulf between the residents of his Central Park West and Willimantic buildings is vast, a reflection of the yawning inequities in the country as a whole, and the budgets are commensurately far apart. But Stern’s goal as an architect remains the same: to design a building that is handsome, respectful, of very high quality, and pleasing to the people who live there. A remarkably democratic attitude runs through his writings and his practice: design that nonexperts appreciate is better than design they hate, and the more they appreciate it the better it is. In the upper reaches of the architectural profession, that is the minority view.

“It’s nice to do buildings that people like,” Stern says, with an impish smile. “I’m not sure all my colleagues get to enjoy that.”