The architect Eero Saarinen celebrated his 51st birthday on August 20, 1961, and the next day paid a visit to a doctor, who diagnosed a brain tumor. A week and a half later, he was dead. Had he lived into his nineties, he might have weighed in on how to rebuild the World Trade Center. Instead, in a scant solo career that flourished only after the death in 1950 of his father and partner, Eliel, Saarinen worked hard enough to produce half a dozen masterpieces, a few duds, and a catalogue of imperfect innovations, all designed for an optimistic age. Critics accused his architecture of lacking identity, of picking a “style for the job.” But what coursed through his supple lines and motley textures was the unifying certainty that today was pretty wonderful and tomorrow would be better still.

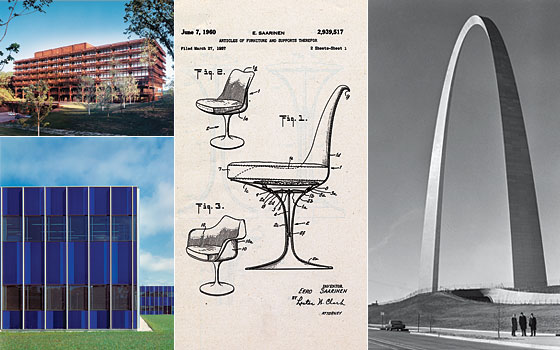

The touching and evocative exhibit “Eero Saarinen: Shaping the Future,” at the Museum of the City of New York, coincides with the publication of Barbara Ehrenreich’s Bright-Sided: How the Relentless Promotion of Positive Thinking Has Undermined America. Yet the show makes today’s smiley-face propaganda machine seem dinky compared to the vast infrastructure of sunniness that Saarinen helped erect: the buoyantly glamorous TWA terminal at JFK; the General Motors Technical Center, with its sharp creases and comely cherrywood curves; the billowing roof and upturned prow of the Ingalls hockey rink at Yale. Even the somber CBS building—that midtown Stonehenge faced in stippled black granite—suggests a company sure of its perpetuity. And of course there’s the triumphal Gateway Arch in St. Louis, setting off an infinitude of prairie sky with a slender steel frame.

One of the most poignant artifacts in the show is a clip from “American Look,” a 1958 promo film made by Chevrolet extolling the glories of industrial design. Saarinen’s GM Technical Center stars as the inspirational workshop, where designers model full-scale Chevys out of clay to refine their figures, fins, and trim. In one fleeting scene, an executive with a briefcase clutched in his swinging fist strides through the lobby to the staircase, a cable-hung beauty with shallow steps that force him to slow his gait—just enough, perhaps, for him to appreciate working in a masterpiece of contentment.

It’s hard to look at Saarinen’s designs now without tasting a slightly bitter draft of ruefulness. TWA sits gorgeously empty and GM’s Technical Center recalls a blighted industry’s better days. Meanwhile, Mad Men turns design into a form of luxuriant oppression. Executives slump in Saarinen chairs, drink themselves numb out of gold-banded tumblers, and do quiet battle across Knoll desks. Comfort does not come easy. Like every generation, we observe the past with fascinated superiority: They lived so beautifully, how could they have been so naïve? Saarinen’s reputation faded in the years after his death partly because he so obviously believed in a future that would soon seem irretrievably quaint. There was, as one critic put it reproachfully in 1962, “no irony” in his corporate work.

Saarinen did contribute to the nation’s self-delusion. He turned his share of farmland into office parks, took for granted an endless supply of fossil fuels, and projected American might overseas with an overweening embassy in London. He served every shaper of the country’s mores: the government, universities, churches, and world-conquering corporations like IBM, John Deere, and General Motors.

The architect of that age of certainty had to overcome a congenital tentativeness. He sometimes got lost in the feedback loop between research and imagination—no sooner had TWA accepted a design for its terminal than Saarinen promptly scrapped it and asked for another year. A more decisive architect would have picked an orthodoxy and stuck with it; Saarinen regularly reinvented himself. At the 1959 “kitchen debate,” Nixon informed Khrushchev that Americans enjoyed fuller lives than Soviet citizens because they had choices in what to buy. Saarinen extended that principle to architecture, treating history as a department store of ideas. For his Morse and Stiles residential colleges at Yale, he tossed stones into wet concrete and fashioned an irresolute New England version of a castellated medieval hill town. For the far more successful John Deere headquarters in Illinois, he fused the industrial and the bucolic, setting in a crafted landscape a manor ribbed with rusting Cor-Ten steel. With its deep shadows and autumnal coloring, the building invites the slanting light of late afternoon; it is at once brawny and picturesque.

All the references and theatrics made purists so censorious that Saarinen felt compelled to confess a weakness for arbitrary acts of beauty. His bubble-on-stilts water tower at General Motors, he admitted, “is a departure from the completely rational.” And yet his inspiration was just as classical as that of the first wave of modernists, who sought a stripped-down lightness reminiscent of Greek and Roman temples in their bleached and ravaged state. Saarinen explored other aspects of antiquity: complex plans, clustered buildings, broad domes, muscular masonry.

The exhibit rides a wave of reappraisal, driven by the popularity of his womb chairs and tulip tables, by preservationists who fought to reclaim TWA, and by architects who have carried on his search for theatrical forms and expressive technologies. The thin blue membrane of glass with which Saarinen wrapped an IBM facility in Minnesota proved unequal to the winters, but it has recently rematerialized in Jean Nouvel’s glowing blue cube of a concert hall in Copenhagen and Bernard Tschumi’s blue-on-blue glass tower on the Lower East Side. The tilted supports and upswept roof at Dulles airport crop up in nearly every Santiago Calatrava project. And you can see TWA’s concrete swirls in Frank Gehry’s baroque undulations and Zaha Hadid’s frozen slipstreams. But while these auteurs developed brands, what spurred Saarinen was something harder to reproduce: a sense of common destiny and the dogged pursuit of joy.

Eero Saarinen: Shaping the Future

Museum of the City of New York.

Through January 31.