Something disorienting—and fascinating—is occurring at the Museum of Modern Art. It’s becoming just a museum. A great museum, to be sure, but just a museum.

At its reopening in November 2004, MoMA emerged with a lavish new building, reorganized collections, and enthusiastic reviews. It seemed to have recast itself for the 21st century, prepared to reassume its role as the shepherd of the new. Attendance during the inaugural year was 2.67 million, roughly a million more visits annually than occurred during the nineties. Museum membership has reached 100,000. Yet the art world today is unhappy with MoMA. Over the past year, the uneasiness has jelled around a single word, repeated again and again, which now hangs like a sign around the museum’s neck: corporate.

On the first anniversary of the new MoMA, Jerry Saltz in the Village Voice and Jed Perl in The New Republic both attacked the institution for becoming bland, mainstream, and safe. Few outside the museum mustered a defense. These articles, by critics from different corners of the art world, brought a developing consensus to the surface. No one doubted that MoMA remained the preeminent museum of its kind anywhere. (As its photography curator Peter Galassi drily observed when considering various complaints about MoMA: “Compared to what?”) But MoMA was traditionally a living idea, not a static monument. It aspired to be the center of an arts community. It considered itself an edgy institution that challenges and instructs.

MoMA is well aware of the art world’s anxiety. Its director, Glenn Lowry—who no doubt anticipated a grace period after his successful fund-raising and building efforts—says simply, “I take all criticism of the museum seriously.” The essential issue is one of metaphysical perspective. At the time of its 2004 opening, the new MoMA delivered what in retrospect were a series of destructive blows to its image. It launched its new exhibition space not with a forward-looking idea but with a showcase of the corporate UBS collection. Making that the inaugural exhibition sent a demoralizing signal about the institution’s priorities. Even worse, the new $20 admission fee implied that the museum cared little for the living community of artists and intellectuals in New York, many of whom are young, poor, and a cherished part of MoMA’s audience.

Many in the working community of artists were also worried by its treatment of contemporary art. Substantial new space in the building was given to contemporary work, but the first show turned out to be a shapeless barn of a survey. Future programming appeared stodgy, with predictable coronations of well-known figures such as Brice Marden and Richard Serra. Where were the shows that would boldly set out to define, rightly or wrongly, what matters in contemporary art? And didn’t the P.S.1 outpost in Queens, where art by younger artists is often shown, marginalize living art? And why was the Robert Rauschenberg “Combines” show at the Met instead of MoMA? At the Met opening, Rauschenberg himself asked a friend from MoMA with plaintive humor, “What am I doing here?”

At the same time, the museum’s internal culture seemed to be changing. Traditionally, MoMA’s benefactors regarded themselves as patrons, not bosses, and its administration treated curators much as university officials treat important professors. Strong-minded curators were the public face of MoMA. Their disagreements made MoMA famously messy, and even the strongest had major weaknesses. For example, William Rubin had a triumphalist sensibility, turning Picasso into a kind of secular god, and he placed the museum’s pictures in an academic straitjacket. But he also gave the art world definition. He was useful to resist as well as to admire.

MoMA may be an expression of a larger, moneyed malaise—an all too true reflection of what we’ve become.

Many critics fear that Lowry is now smoothing out necessary edges, reducing the curators’ status within the museum and their public presence outside it—transforming a brilliant if dysfunctional family into bureaucrats. Of course, it’s almost impossible to find a curator who can be a scholar, critical warrior, collector, administrator, and public showman all in one. But MoMA has recently lost two such figures. Illness forced the head of the department of painting and sculpture, Kirk Varnedoe, to leave the museum at the end of 2001. And Robert Storr, the strongest curator of contemporary art of his generation, left the museum in 2002; he and Lowry did not get along. The moral for the art world was disturbing: MoMA could not find a way to keep a powerful voice.

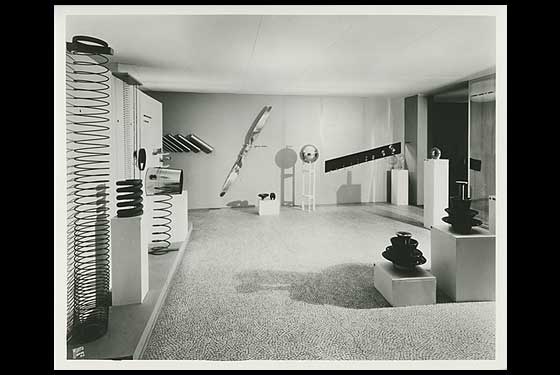

The building’s architecture is now regarded as the embodiment of these concerns. Detractors call it passive, without the necessary modern fire, its subtleties destroyed by the large crowds. In particular, they object to the big, almost empty atrium. Originally, the architect, Yoshio Taniguchi, intended this atrium to be an interior sculpture garden, which would have created an elegant rhyme with the outdoor garden and marked an artful transition into the galleries. Since the museum needs the space for special events, however, curators have not done that, instead hanging big paintings in the echoing space without much success. This is also developing into a symbol: Is the museum empty at the center? Are the parties more important than the art?

It’s often overlooked that the conditions MoMA faces have radically changed. In the forties and fifties, the rest of the world, exhausted from World War II, could not buy, display, and analyze modern art the way an American institution could. In the 21st century, the art world at large has caught up, and modernism has carried the day. MoMA can no longer easily behave like a private club when millions of people bang on its door. Contemporary art itself has joined the mainstream, its controversies often nothing more than a faux titillation. Art now does not often invoke bold new worlds; it can’t often claim to represent something radically new. That’s what’s probably most troubling to people: MoMA may be an expression of a larger, moneyed malaise. It may be an all too true reflection of what we’ve become.

The museum certainly should not retire gracefully into its pretty white shell—not without first engaging in a steely round of self-examination. Some moves seem obvious. It should organize its special events in another way and try to make the atrium one of the strongest sculptural spaces in the world. It continues to have smart and talented curators, like Galassi and John Elderfield, but it must take pains to develop a robust curatorial culture that, in particular, can assert a powerful vision about contemporary art. Vision—not reportage, not survey, not coronation. The museum must provide some shape, rightly or wrongly, to the complex morass of art beyond its doors.

When it was founded, MoMA considered holding on to works of art for only a few years and then passing them to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In that way it hoped to remain forever fresh. Today, the weight of its collection is enormous. Perhaps it’s inevitable that MoMA will subside into being a museum. Perhaps that’s not even bad, but a useful signal that what we call the modern and postmodern periods are retiring into history. If the art world remains impatient with MoMA’s treatment of art, perhaps it should consider alternatives. There are people today as wealthy as the Rockefellers were when they helped start MoMA. There are curators as eager to develop the new as Alfred H. Barr Jr. was in the thirties. Is there the cultural will? Let someone bold found a new museum for the 21st century.