In the dimly lit living room of his Washington Heights apartment, Edward Mapplethorpe hears his brother’s voice and turns around. “There he is,” he says brightly, as if Robert Mapplethorpe had just walked into the room, late for a meeting. In the flickering image on the screen behind us, Robert is mischievously smiling, smoking a joint. The footage was shot in 1985 by the photographer Lynn Davis. In it, we see Edward, Robert, and a few other people hanging out in Robert’s loft. Robert and Edward, who looked so much alike back then, take a seat on a couch and begin to look at the galleys of Robert’s first book, Certain People. When Edward watched the film for the first time a couple of months ago, he ran the gamut of emotions—from tears to anger to laughter—and then fell into an exhausted heap for the remainder of the day. Even now, he is a bit twitchy watching the footage. “He wants me to look at his book,” he says, “but he’s turning the pages.” And then he says something he’ll say many times in the course of our conversations: “I don’t want to focus too much on Robert.”

Edward, whose career began in 1982 as his brother’s studio assistant and who has finally emerged as an extraordinary artist in his own right, has never had much of a say in the matter. He, like many people, was drawn into his brother’s creative universe, a world of subversive sex and hard drugs, obsession and ambition, darkness and beauty. By the time it was over, when Robert died of aids, in 1989, Edward was addicted to heroin and struggling to find his own creative way—a virtually impossible task in the long shadow of his brother’s legacy. After a few shows in the early nineties, Edward withdrew from the art world almost entirely. But he never stopped making art. In the center of Edward’s living room is a custom flat-file cabinet that holds 25 years of his photography—from a series of spooky underwater pictures to his astonishing commissioned portraits of 1-year-olds—in meticulously organized drawers and boxes. This fall, he is having his first gallery show in New York in thirteen years, at the Foley Gallery. The new work—lithographic prints of abstract photograms that are made with horse hairs—is a breakthrough for Edward, much closer to painting or drawing than photography. Indeed, the prints barely look like photographs at all.

As we stand at the cabinet flipping through the series, Mapplethorpe looks back to the scene on the screen from two decades ago, to his 25-year-old self who did not know that terrible things were about to happen. “When I see this,” he says, “I’m like, ‘You’re still innocent here! The shit is going to hit the fan! Can I rewind?’”

Edward barely knew Robert when they were growing up in Floral Park, Queens. He was only 3 years old—the youngest of six children—when his brother started commuting to the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, 4 when Robert moved out of the house for good. Robert was transformed by the sixties, growing his hair long, taking LSD, going to art school, and generally rebelling against his rigid Catholic upbringing as if following a script. Their father, an exceedingly practical and conservative man who worked his entire life as an engineer at the Underwriters Laboratories on Long Island, was appalled by his son’s behavior and disappointed in his career choice. Robert almost never came home, and when he did, says Edward, “my father wouldn’t talk to him. He would hold his hand in front of his face and say, ‘I can’t look at you!’ ”

On one of his rare visits, when Robert was 20 and Edward was 7, Robert brought with him a young singer and poet from South Jersey named Patti Smith. “The one thing that I remember very clearly,” says Smith, “was that I looked at the two younger brothers and James was sort of a dark-haired, moody kid who resembled Robert a bit, and Eddie was just a freckle-faced imp. I said to Robert, ‘Do you think James will become an artist?’ And Robert said, ‘Oh, no. Eddie’s the one.’ I said, ‘How do you know?’ And he said, ‘I can tell. He’s the one.’ ” A year later, Smith gave Edward a book, Marc Chagall: Art for Children. It is inscribed EDDIE, HOPE YOU’LL BE ONE TOO SOMEDAY. PATTI.

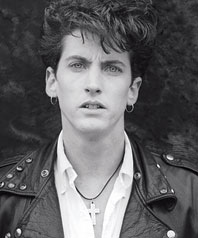

Despite his father’s disapproval, Edward was taken with the iconoclasts who occasionally showed up at family gatherings. Edward shows me a photograph taken at his eighth-grade graduation from Our Lady of the Snows. Edward is walking down the aisle in cap and gown, and there is Robert, standing off to the side—in full black leather. “I was like, Oooh, this is weird,” says Edward. “But I also thought, This is cool.” That was about the time Edward started seeing Robert less as a brother he hardly knew than as a rock star whose acquaintance he had made.

“Something instinctively in me knew that I did not want to be involved in the blue-collar-white-collar world of Queens,” he says. “And Robert was an example to me that there was something outside of that world. He showed me a path.”

When Edward was 16, he was so curious about his increasingly famous brother’s life that he called him one day and arranged a visit. He took the subway from Queens into “the city” to Robert’s infamous Bond Street loft. In a 2006 documentary, Edward described the visit: “It was a very darkly lit space, a lot of devil figures. He had Ed Ruscha’s Evil piece up over his bed … I was nervous, meeting this brother that I didn’t know … He put an eight-by-ten book of photographs in front of me and said, ‘What do you think of this?’ And there were, right in front of me at 16, these images of leather-bound and hard-core … He said off the cuff, ‘What would Dad think of that?’ And here is some guy peeing in another guy’s mouth. Or the fist-fuck pictures. I laughed at it, but … I think I was so taken by Robert and his lifestyle, I wanted to get to know him.”

One night, Mapplethorpe and I go to dinner at Indochine, the eighties institution in his old stomping ground. A few blocks south, just off Lafayette Street, is 24 Bond, the place where Robert Mapplethorpe would invite his subjects to do drugs, have sex, and then be photographed. As we finish dinner, Edward begins to tell me how he was drawn into his brother’s circle. His fascination with Robert had continued since that first meeting, and he had decided, against his father’s wishes, to study photography at SUNY Stony Brook. He wrote a paper about Robert for one of his photography classes. “Mapplethorpe on Mapplethorpe,” he says with a laugh. “You should read it.” Written in 1981, before his brother became an international sensation, it is a sort of time capsule of their relationship, of Edward’s trying to comprehend this distant brother, his sexuality, his provocations: “Why did I know so little about Robert Mapplethorpe? … After all, he is my brother—isn’t he? Technically, yes; in reality, no.” He writes of a recent visit to the loft, where Robert told his brother he was gay. “Although I was well aware of his homosexuality, I was overwhelmed by his openly admitting it to me that Sunday afternoon. I feel confident in saying that I am the only one in his ‘blood family’ that he would be able to do so. And for this reason, I feel that I stand out from the rest of the family.”

Standing out from the rest of the family made life difficult at home. In December 1981, Edward graduated and found himself directionless and miserable. “My father’s like, ‘Are you going to get a job? You can’t live here.’ ” He later found out that his mother called Robert to ask if her youngest son might go to work for him. Edward was summoned to the Bond Street loft. “He said, ‘I’m not so sure I like the idea of my little brother working for me. I don’t want you to be any sort of link back home.’ ” But they decided to give it a go. “From that point on,” says Edward, “we developed a friendship. He was very proud to introduce me to people. He liked the fact that somebody in his family understood him.”

Edward got quite an education at 24 Bond. His brother’s studio, he says, was “so sexually charged that you needed to be pretty certain of who you were to be around it on a day-to-day basis. If I were gay, I would have gone for it then and there, no doubt.” Working for his brother also inured Edward to the idea of daily drug use. “Robert smoked pot pretty much every day,” he says. “And he liked his cocaine. During a shoot, the subject would go to the bathroom and he would offer me some coke.”

After years of not really knowing each other, Edward and Robert fell into a routine, working in the studio side by side. “They had a very similar temperament, similar character,” says Smith. “Robert loved Edward. He was almost fatherly towards him. He trusted him and depended on him. Edward was a selfless assistant. He always understood the power and ability of his brother.”

Still, Edward’s presence changed Robert’s work in a fundamental way. He brought formal training to the studio—lighting and darkroom skills that his brother lacked. James Danziger, who owned a gallery in Soho in the early nineties and was Edward’s first art dealer, says, “Not to take anything away from Robert, but his early work was kind of rough in a way. Circa 1982, when Robert started producing his trademark twenty-by-twenty-inch square prints—beautiful flowers, portraits—we are seeing Robert Mapplethorpe’s vision sort of run through Edward’s lighting and printing.” Edward reluctantly takes the compliment. “Yes, I was more formally trained,” he says, “but his pictures became so slick. I happen to like the early work better myself, the work he did without me. As far as the darkroom is concerned, Robert hadn’t a clue. He hated the darkroom.”

Edward, on the other hand, thrived in the darkroom. And because he had access to his brother’s equipment, he began to experiment, shooting and developing his own film, as any photographer’s assistant would. Says Danziger, “When Edward first started doing his own work, it was in some cases almost indistinguishable from Robert’s. Robert’s conception was that Edward was copying him; in fact, he was really doing his thing.”

Despite his success, Robert was clearly bothered by the fact that his younger brother was starting to become a photographer in his own right, at one point even complaining that Edward was shooting portraits of his friends, some of whom were black men. This was further complicated by the genetic fact that the brothers looked so much alike. Jack Walls, who was Robert’s boyfriend at the time, says that when he saw Edward from a distance at a Sotheby’s auction of Robert’s work, he mistook him for his boyfriend. Others made the same mistake.

In the spring of 1983, about a year after Edward started working in his brother’s studio, he was invited to participate in a group photography show that also included Christopher Makos, Joel Peter Witkin, Cindy Sherman, and … Robert Mapplethorpe. “I was scared to tell him,” says Edward. “So I just didn’t.” When the invitation came out, “Robert hit the roof.” To make matters worse, Edward was listed before Robert on the lineup. (“E comes before R,” Edward explains.) Walls remembers a night when Robert obsessed about his brother from “one or two o’clock in the morning until the sun came up. It was all about how he thought it would be better if Edward changed his name.”

The next day, Robert invited Edward to lunch. “We went to this diner on 8th Street, and he was very aggressive,” says Edward. “He said, ‘I’m not going to have any kid brother of mine riding on my coattails. I’ve worked hard to get to this point, and if you think…’” Edward trails off, wincing at the memory. “This is the brother I grew up idolizing!” he says, still incredulous. “For him to treat me like that? I was like, ‘All right, all right.’ I wasn’t strong enough to say, ‘Fuck you.’” He pours himself another glass of wine from the bottle on the table. “My mother’s maiden name is Maxey. So I became Ed Maxey overnight. Didn’t make any sense, because everybody knew.” Another sip of wine. “It was ridiculous!”

As we get up to leave the restaurant, we run into a mutual friend, someone Edward hasn’t seen in several years. The friend introduces Edward to his dining companion as Edward Maxey and is immediately and forcefully corrected: “It’s Mapplethorpe.”

“I’m your little brother! You’re worried about me eclipsing your career?”

I met Edward Mapplethorpe when he was still calling himself Ed Maxey. It was a Saturday night in August 1992 and I was at the Sound Factory, the club on 27th Street that was the epicenter then of after-hours nightlife. I ran into two friends who were with Edward. He had an irrepressible smile and beautiful blue-gray eyes, and was quick to laugh. I liked him immediately. We all wound up back at a friend’s apartment for an after-after-party, and at some point I wandered into the kitchen and found Edward and a few others hovering over several lines of powdery drugs.

I had known of Edward Maxey, the photographer, before that night, had seen his photographs in Interview and Paper, but I had no idea that he was Robert Mapplethorpe’s brother until then. I also had no idea how painful his life had become.

His life had begun to come unraveled just as it was getting started, shortly after his first show, after Robert made him change his name. Not surprisingly, Edward grew restless and dissatisfied and decided he had to leave his brother’s studio. “But Robert was complicated,” he says. “He drew people in. And when you were in his world, it was hard to get out. I told him that I was going to move to L.A., and he was like, ‘How dare you leave me?’ He brought me to tears.”

Robert immediately hired a new assistant, Javier Gonzalez, a young, attractive boy he met in Spain who spoke very little English. He asked Edward to stay an extra month to train him, but things in the studio grew tense. “There’s that dark side to Robert,” says Edward. “He thrived on pitting people against each other and people getting in arguments. And it was orchestrated in a very sordid way.” After finally getting to know his brother, Edward was being excommunicated. “Once Javier was there, I was already out of the picture,” he says. “Robert was not being as nice to me. Once he was done with you, that was it.”

Edward moved to Los Angeles and got work assisting photographers who worked for Playboy. That was when he started using heroin—a habit that grew worse as he was rocked by a succession of family tragedies. First, his mother was diagnosed with emphysema, and before he was able to digest that news, his brother Richard, an engineer with whom he had lived in L.A. before he got settled, was diagnosed with lung cancer. By the time the doctors caught it, the cancer had metastasized to his brain, and he was dead within a few months, at the age of 41. Robert had refused to visit his older brother before his death. “His explanation to me,” says Edward, “was, ‘If I was in Richard’s shoes, I wouldn’t want him to see me like that.’ aids was out there by then, and I’m sure he thought, ‘I may very well be in Richard’s shoes.’ It was too much of a mirror.”

It wasn’t long after Richard’s passing that Robert was diagnosed with aids, and Edward moved back to New York to help take care of him. “Unbeknownst to all of us,” says Edward’s brother James, who works for Smith Barney and lives in Massachusetts, “Ed was trying to help Robert through the early years of his illness until Robert was comfortable sharing that with Mom and Dad. That was a very troublesome burden for the youngest member of the family to carry.”

Edward was living in Robert’s studio on Bond Street with a woman named Melody, an assistant to Patricia Field by day and a dominatrix at night. Robert had introduced them, saying to Edward, “If I was straight, Melody would be my girlfriend.” They quickly fell in love. In a portrait that Robert shot of the couple, she is pale as a ghost, nude from the waist up, flat-chested, with a bleached-blonde crew cut—an Annie Lennox clone; Edward looks like Lestat: skinny and pale, long hair in a ponytail. “I think I only weighed 120-some-odd pounds,” he says. Were the two of you doing heroin? I ask. “Yeah,” he says. “Big time.”

“I’d be a lot more successful right now if he had just given me his blessing. It pains me that I never got that.”

As Robert grew sicker, he was confined to his bed in his apartment on 23rd Street, and Edward found himself in a strangely familiar role, working for Robert in the studio—only this time his brother wasn’t there. At night, he and Melody would bring Robert dinner from McDonald’s, the only food he wanted to eat. “Melody used to entertain Robert like you wouldn’t believe. Every time she would come as another character—she had all these wigs, 300 pairs of shoes. We’d sit and watch TV until he was ready to go to sleep and then go back to the loft. It was just…tiring. I was tired. I was burying my feelings and doing drugs. People have since told me that everybody in the studio knew. Robert probably knew, too.”

Two days after New Year’s Eve in 1989, Edward went to see a doctor, desperate for help with his addiction. “I was in tears, just a wreck. I said, ‘My brother’s going to die in a few months. If he leaves me any money, I’m going to be dead, because I know where it’s going to go.’”

Robert’s imminent death inspired a feeding frenzy. Everyone knew that his photographs—many of which had as their subject the very thing that was killing him—would soon be worth astronomical amounts of money. “When someone’s dying and there’s an estate,” says Edward, “it’s a weird dynamic that gets set up and people are hanging around. It was a really ugly time.” Toward the end, Robert’s hospital room took on a circus quality that Edward could barely stomach. “There were a lot of people in the hospital room, and it was just too much,” he says. “Because it was like, ‘Is that his last breath? Is this his last breath?’”

When Robert died, Edward and Melody were informed that they had to move out of the Bond Street loft. Robert’s studio now belonged to the Mapplethorpe Foundation, and it wasn’t long before “there were locks on everything,” says Edward. Robert had set up the foundation to guard his legacy, raise money and awareness for aids research, help promote photography in the art world—and keep his estate out of his family’s hands. (Robert did leave Edward “a nest egg,” Edward says.) The foundation is run by Michael Stout, a lawyer, who told a reporter last year that Robert’s “primary focus” when they were planning his estate was to “disinherit his family … His family wasn’t bad. What he disliked about them was that they were ordinary.” The antipathy was mutual, at least from his father’s point of view. In one of the few interviews Harry Mapplethorpe ever gave about his son, he is asked, “Are you proud of your son?” Big sigh. “For the artwork he did, yes,” says the father. “But for some of the photographs that he took, I just could not accept them … Admitting that he was gay … that wouldn’t have helped matters at all. Because I probably would have more resentment if he had told me.”

Edward says he now has a good, if hard-won, relationship with the foundation, though he’s never been asked to serve on its board. “It’s sad not to have a family member somehow involved. Robert sort of missed the point … again. There are a few points that Robert missed,” he says. “To have Robert die with this big estate and there’s not one mention of my mother and father? Wow, Robert, why did you do that? You wouldn’t have been who you were if you didn’t have those parents to rebel against. I mean, on your deathbed, I would hope that you would somehow come to peace with that.”

It is Edward’s greatest regret that he was never able to bring his brother and his father together. “I thought I was destined to be a catalyst between them,” he says. “It has been the source of so much pain. And the worst part of it all is that I was unsuccessful. It’s probably the saddest part of my life.”

I lost touch with Edward a few years after we met. I no longer saw his work in magazines, and I imagined the worst: that he had gotten lost to drugs. The reality was more complicated. Much more difficult than his battle with addiction was his struggle to figure out who he was in the wake of his brother’s death. Who was he if not the kid brother of a famous artist who was not allowed to use his last name? “For a long part of his life, he completely negated his own DNA by using the name Maxey,” says his best friend, Michael Flutie. “That has to have a huge influence on who you are as an artist. You’re shadowed by somebody who is much bigger than you are, and at the same time, you have no connection to who you are as a person. Edward had to go to an extreme place in his life just to understand who he is.”

Edward did a few shows in the early nineties that got a fair amount of attention. “It seemed like the light at the end of the tunnel for me,” he says. “It was like, Wow. After all that hardship and death and all those drugs, obviously it’s my time now.” But he couldn’t seem to escape his brother’s influence, or his shadow, which had only grown since his death, and he didn’t like the work he was doing. His last show at the Danziger Gallery was a series of black-and-white photos of the American flag. Naturally, the first thing they brought to mind was Robert Mapplethorpe’s famous and iconic photograph of … the American flag. “I wasn’t ready,” he says. “I hadn’t matured as an artist or thought about what I wanted. And it didn’t work. It wasn’t genuine.” He couldn’t figure out how to be Edward Mapplethorpe, and so he disappeared.

It was a surprise when, in June of this year, I got an e-mail from Edward saying that he was having a show in New York this fall and that he had a new dealer, Michael Foley, in Chelsea. “As you are aware,” he wrote, “it has been some time since I have wanted to put myself out there … But I think once you see the work you will understand why I’ve waited so long. It is finally the piece to the puzzle … that links my past to the future.”

I went up to Washington Heights and saw the evidence of an evolution. He had been working all along, of course, making beautiful, surprising prints, but also moving away from portraiture and figurative photography and the studio—the place where his brother thrived. Indeed, with his latest work, Edward has taken the camera out of the equation entirely, working exclusively in the darkroom: his domain. His photograms are in the tradition of Man Ray or, more recently, Adam Fuss, and yet they are more painterly and abstract. In many ways, his work is about the basic elements of drawing—pattern, circle, line, repetition—except in this case, he is drawing with light. The work is at once influenced by his brother yet completely his own. Something Robert Mapplethorpe could literally never have produced.

On the night of Edward’s preview two weeks ago in Chelsea, he seemed relaxed and happy, surrounded by his friends, his art-world associates, his girlfriend of over ten years, Michelle Yun—and connections to his brother: Jack Walls, Patti Smith, people from the Mapplethorpe Foundation. Stenciled in big letters on the white-white wall of the gallery was his name: EDWARD MAPPLETHORPE.

One afternoon, we go for a walk on Bond Street and peer into the dirty peephole-size window on the door to the lobby of his brother’s old building. Edward has not stood on this stoop since just after Robert died, and I can feel his discomfort as he strains to see into the past. “It looks exactly the same,” he says. We pick our way along the construction zone of luxury real estate that Bond Street has become, and Edward points out the route he used to take to score his daily heroin fix. When we stop for lunch, I ask him if he thinks Robert was threatened by him. “The most seemingly secure people in the world are the most insecure. The fact that he would be like, ‘You have to change your name’? I’m your little brother! You’re worried about me eclipsing your career? It’s ridiculous. But I’m sure that’s what it was. And then in his later years, he had to be envious because I was going to live. He wasn’t like, ‘Edward, take the bull by the horns and continue this thing.’ I wish he had said that. You can’t ask for something like that. I was always just sitting and praying for it. Even on his deathbed. Somehow, just give me a sign that I’m doing the right thing. That you’re happy, that you’re proud of me.” He starts to cry. “It just pains me that I never got that. I’m sure my career would be a lot different, I’d be a lot more successful right now, if he had just given me his blessing. If he had just said, ‘You know what, I admire what you’ve done.’ ”

He wipes his eyes. “And sometimes I think, Could you have chosen a more difficult path? I can’t think of one that would be worse!”

I ask him what he wants now that he seems to have come to a turning point in his work. “I don’t need to have millions,” he says. “I don’t need to be a superstar. I would like to be respected by people in the art world and have people appreciate what I do. I don’t need to be Jeff Koons. I don’t need to be … Robert Mapplethorpe!” This makes him laugh. But then, quietly, he says, “He did. He needed to be Robert Mapplethorpe.”