If you decide to live without a home—that is, with no lease or mortgage or roof to call your own, entirely at the mercy of friends, family, patrons—it might behoove you to be as handsome and charming as the Italian artist Francesco Vezzoli, who has a Roman nose and longish brown hair that he slicks back, but not so much that it doesn’t fall, sometimes, into his serious, dark eyes. RoseLee Goldberg, the director of Performa 07, the performance-art festival that has commissioned Vezzoli’s next big project, which will take place on October 27 at the Guggenheim, says of him: “I am convinced that Francesco is made of white chocolate.” She then clarifies. “Everyone he meets just falls in love.”

Vezzoli has, over the past decade, become art-world famous for a flashy body of work that reinvents kitsch with the invaluable assistance of celebrities. He’s done needlework studies of Scavullo portraits, sent up Caligula, and produced a video dating game starring Jeanne Moreau and Catherine Deneuve as the lucky bachelorettes. These are often lavish productions—think YouTube footage as financed by the Medicis—and Vezzoli has found generous patronage in the fashion world, largely through Miuccia Prada. (“You might think me cheesy,” he says regarding his adoration of Prada, “but is the best. A friend, but also, I idolize. I am a lucky man.”)

For a few months now, he’s been living at a certain posh Soho hotel that Vezzoli asks not be named lest people find him “too fancy—and I don’t want to sound fancy. Please.” He’s been working on his Performa piece, which is being produced in conjunction with the Gagosian Gallery and which is, in Vezzoli’s words, “the premiere of a play that will never run, contextualized in an artistic frame.” The play is Pirandello’s Right You Are (If You Think You Are), and the “premiere” will star Cate Blanchett, Natalie Portman, and David Straitharn and, potentially, probably, Vezzoli himself.

Vezzoli claims to hate appearing in his own work—“That’s the biggest amount of pain ever. I hate to do that. I hate, I hate. I swear.” But he does it all the time. “I do it because I have to do it,” he says, “because I think it gives more meaning if you put your face there.” There are whisperings about what involvement Miuccia will have (“You will have to wait and see,” he says with raised eyebrows), and Vezzoli is toying with the idea of inviting Woody Allen, whom he does not know. He is definitely inviting David Byrne and Cindy Sherman, whom he does know and whom he recently saw walking together on a New York sidewalk. He went right up to them and said, “The fact that you are in love is like an answer to life.”

Like many artists, Vezzoli, 36, is deeply invested in his own self-mythology, referring to himself regularly as “just a boy from the provinces,” which he is, in a sense. He’s from Brescia, a small Northern Italian city in the foothills of the Alps. He still spends a bit of time at his parents’ house there, and it’s where he sends anything he makes the mistake of accumulating, but he is committed to his vagabond lifestyle. (Though the last time he did have an apartment, in Milan, he was delighted to find that the rent was paid on his behalf. “I suppose my father paid it,” he admits. “Someone did.”)

“I understand that people need a home,” Vezzoli says over lunch at Savoy, “but for me, life is different. It is an intellectual choice. I am dedicated to my work. My brain is clean from so many burdens: pillows, doors, cleaning the carpet. And bills! There are people who want to be paid because they have cleaned the house … I see a home and I see impediments. How can I produce my Pirandello if I also have to produce a house?”

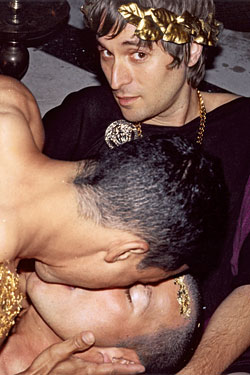

The Performa commission follows Vezzoli’s splashy offering at last year’s Whitney Biennial: Trailer for a Remake of Gore Vidal’s “Caligula,” starring Vidal, Helen Mirren, Milla Jovovich, Courtney Love, and Vezzoli himself, as the ambisexual, incestuous emperor in a purple toga and leafy little headdress designed for him by Donatella Versace. It was shown in a mock movie theater complete with red velvet curtains, and was, in Biennial terms, a smash success—one of the few things that anybody liked well enough in the show to still remember today.

Vezzoli’s liberation from dirty dishes and waiting for the plumber has also, of late, enabled a campaign video called Democrazy, starring French philosophe Bernard-Henri Lévy and Sharon Stone as American presidential candidates, as well as A True Hollywood Story commissioned by Gucci bigwig (and Salma Hayek baby-daddy) François-Henri Pinault, in which a mock panel of commenters conclude that Vezzoli is a “pushy little shit” guilty of exploiting former model Verushka and of making a pornographic film starring Bruce Nauman’s shiny, bouncing testicles.

Next year, with the support of the Fondazione Prada, Vezzoli will begin a Kinseyesque survey of the sexual habits of Americans. He’d like to follow that up with a ballet at the Bolshoi; an opera, maybe in New York, maybe at La Scala; and an archaeological expedition.

Because Vezzoli exists at the center of the art-celebrity-fashion nexus that is, controversially, defining the art world now—witness the cover of W magazine’s art issue, in which Richard Prince “autographs” head shots of Julia Roberts and Britney Spears—he spends a huge amount of time negotiating a position about it all. “I am trying to analyze the fact of celeb- rity culture,” he says. “It is more and more strongly related to the dynamics of the art world.

“In Europe, in the past, the collectors were hypersophisticated people,” he adds, the implication being that collectors were discreet enough to stay out of artists’ hair, and this, perhaps, is no longer the case. “Artists in one way or another have to adjust to the Establishment being closer to contemporary art than it ever was. It’s nobody’s fault, it’s just a very natural dynamic. We are the object of desire of so many structures.

“I am often accused of wanting it both ways,” he admits, “to share in the celebrity of my actors, but at the same time, I crave for a sort of intellectual acceptance.”

Vezzoli has long been fixated on having it both ways: He wrote his thesis for Central Saint Martin’s College of Arts, in London, about homosexual subtexts in a Brazilian telenovela, and he explains that these days he’s over having it both ways sexually (“I realized I cannot fuck women, but I love women, so I work with women”) and is far more interested in having it both ways famewise. In A True Hollywood Story, a faux critic ascribes Vezzoli’s faux demise to his love of fame: “He thought that by drawing celebrities into his work, he would become a celebrity.” In Vezzoli’s mock critique, this leads to endless watching of The Golden Girls (even when young rent boys are there to distract him) and obsessing over Marlene Dietrich before his eventual death in a glassy Hollywood pool.

Right You Are (If You Think You Are) is, in many ways, an examination of celebrity culture: It is about what happens to one’s identity when it is the subject of intense speculation and projection. At the heart of the play is Madame Ponza, a women who, in her absence, is assigned any number of identities by the people of Chaos, the town where she lives. She is this one’s wife, that one’s niece, etc. “It is a perfect mirror for the studies I do of public identities,” Vezzoli says. “Because the woman basically claims that she has no identity in function of all the identities that are applied to her.” And who better to do it than Cate Blanchett, who has been busy recently adopting identities not her own—Bob Dylan, Queen Elizabeth.

As for Vezzoli’s role: “I am not the director, I am the enabler,” he says. “If you ask me, Nijinsky or Diaghilev, the answer is Diaghilev. I mean, I love Nijinsky. But Diaghilev. This is my Ballets Russe. Forgive me the ambition, but I try.”

“I very much appreciate Francesco’s work,” says Miuccia Prada, “because of the strong political content that is generally underestimated. What people get is usually the involvement of famous people, but what is really powerful in his work is the deconstruction of the mediatic system.”

And then, of course, it’s just really fun to meet all the famous people you’ve always admired. “If you are true to your art,” Vezzoli says, “you use your professional identity to meet people you like, which sounds horrible. But I’ve used my projects to meet people I am passionate about. I have an obsession for Gore Vidal, you know, so there you go.”

SEE ALSO: Francesco Vezzoli: ‘Pushy Little Shit’