In mid-August at the Queens Museum, the intrepid artist Duke Riley—once arrested for piloting his makeshift submarine too close to the Queen Mary 2—staged a mock battle between art museums in a Flushing Meadows pool. Employees of various institutions, ensconced in homemade ships, laid siege to each others’ vessels; the crowd was encouraged to get in the water and throw tomatoes. Riley conjured something intoxicating and joyous that had been missing of late: the ambition, competition, and sheer effort it takes to make art and museums great.

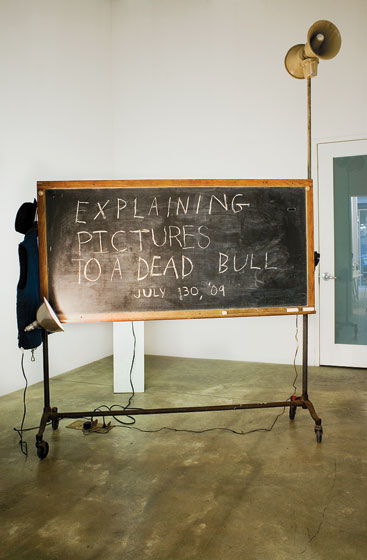

Two weeks earlier, I sat transfixed listening to Explaining Pictures to a Dead Bull, a cutting and cute send-up of art history by a loose collective of young artists known as the Bruce High Quality Foundation. These human bullshit detectors aim to provide “an alternative to everything”—their mission, to call out an art world “mired in irrelevance.” At the event, artists lectured from a pithy script dealing with “contemporary art as a futures market,” “corrupt business practices,” and Mark Rothko. Since the summer, the collective has opened an actual school that anyone can attend, the Bruce High Quality Foundation University, a.k.a. BHQFU, a free, unaccredited school in Tribeca where artists propose courses and interested others sign up to take them. As the Bruces write, “The $200,000 debt model of art education is simply untenable.” Amen.

Such giddy, refreshing events came in the wake of everyone’s saying that the gallery world is dead or dying. And that don’t-settle-for-business-as-usual dynamic continues next week at Chelsea gallery Foxy Production, which has Sterling Ruby’s new show, intense and uncomfortable videos of male porn actors masturbating alone in empty rooms. I saw a video from Ruby’s project at MoMA this summer, and it brought me back to a what-the-hell moment in 1972, when Vito Acconci masturbated under the floor of the Sonnabend Gallery.

Over on the Bowery on October 28, the entire New Museum (kind of like a gallery on steroids) will be devoted to the New York–based Swiss artist Urs Fisher. Fisher is one of those creating-destroying gods whose sculptural-architectural interventions push ideas, space, and viewers to wonderful extremes. In 2007, he dug a gigantic crater in the floor of Gavin Brown Gallery in the West Village and seemed to turn the art world upside down. At the New Museum, he will, among other things, install environments intended to transform the museum into a “dazzling cityscape.” Whatever the results, the provocative Fisher is incapable of banality.

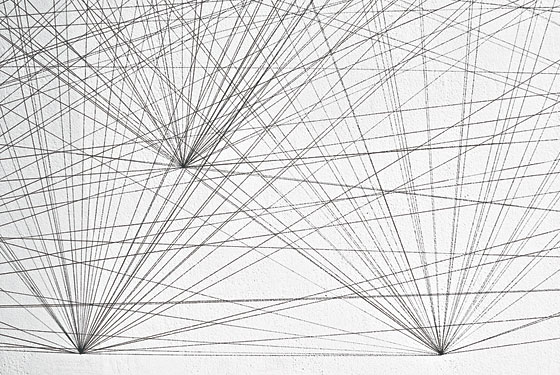

Similarly novel is Eric Doeringer, whose current show of perfectly replicated early Sol LeWitt wall drawings is at the tiny Dam Stuhltrager Gallery in Williamsburg. Instead of this being yet another hipper-than-thou exercise in appropriation, Doeringer—who will be familiar to Chelsea gallerygoers as the young man seen selling reproductions of artworks by Damien Hirst, Elizabeth Peyton, and others—functions like a tribute band, someone faithfully providing a genuine aesthetic experience, not just a knowing scold.

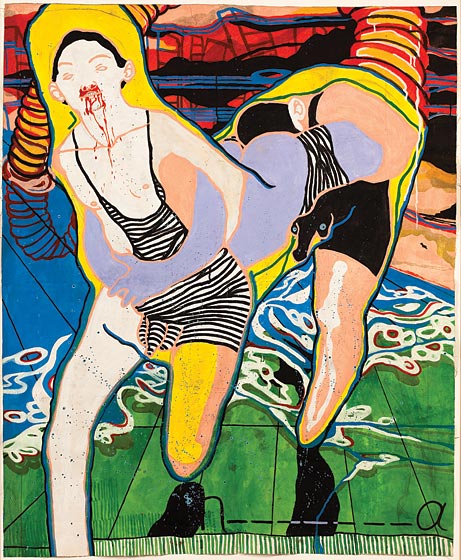

That kind of faith, and what I like to think of as “radical vulnerability,” is currently in evidence at the Zach Feuer Gallery in Chelsea in the Russian-born New Yorker Dasha Shishkin’s exhibition, in which the artist’s lyrically lined drawings and paintings evoke an avant-garde twenties salon, a little girl’s room, and a circle of hell.

All of this is to say that the demise of the art world has been greatly exaggerated, including by me. It’s as if a bunch of spotlights went out when the market crashed last October, and now, as they flicker back on, we’re able to see new green shoots busting out of the establishment’s cracks. The plug was pulled, but life went on—invigorating life. There might not be a new movement, per se, but there are radically adjusted mind-sets. Fear of form, color, and physicality are diminishing. Previously forbidden methodologies are reemerging: pours, patterns, laminations, complex (even mystical) counting systems, obsessive mark-making and surface manipulation, suggestions of still life, digital motifs, even trompe l’oeil. Artists are—hallelujah!—finally tiring of recycling Warhol and Richter and are instead investigating the handmade, and how irony and sincerity can coexist.

Gavin Brown, Canada, Lisa Cooley, Rental, Klaus von Nichtssagend, Sue Scott—all of these galleries and more are exhibiting the work of rambunctious nonconformists. Until October 17 you can even catch a glimpse of a possible future in three solo shows at the one-year venture known as the X Initiative. Tris Vonna-Michell, Keren Cytter, and Luke Fowler work in performance, video, sound, and other time-based media. The trio treats non-material things like narrative, JPEGs, sound, psychology, philosophy, and fiction as raw materials. They’re looking beyond the art world to the whole world.

Similar expansiveness extends to the galleries themselves. Within the bad news of closures (some, arguably, for the best) and slashed budgets and prices (“a 30 to 40 percent discount is the new 10 percent,” says dealer Kenny Schachter wryly) is the remarkable fact that more than 30 galleries have opened since last year. They are struggling, for sure, and will for a while. The Lower East Side dealer Lisa Cooley, who opened her tiny Orchard Street space in January 2008, admits, “I had a terrible July and August, but because my economic ecosystem is so tiny, I can recover with a $2,000 sale.” But while she and a number of her neighbors—Miguel Abreu, Rental, Dispatch, Half Gallery, Small a Projects, Simon Preston, Rachel Uffner, and Reena Spaulings—might not be thriving, they are surviving, which, when compared to the art-market collapse of the mid-nineties, is a triumph in itself. “Back then,” says art advisor Allan Schwartzman, “there was a complete loss of confidence. No one bought anything. Everything fell apart. Now people are spending less, but they are spending. Collectors sidelined by the recent hysteria are finding ways to buy in this slowed-down market. A few, finding greater opportunities, are spending more.”

Whatever happens, this fall’s gallery scene is full of freewheeling energy, a willingness to fail in new ways, and a contentiousness that doesn’t speak to the same 250 insiders—and not just with emerging artists. Right now, at the SculptureCenter, you can see a rollicking, mind-blowing installation by Mike Kelley and Michael Smith. Later this month, Alpine shamans Peter Fischli and David Weiss take over three of Matthew Marks’s Chelsea Galleries. But don’t take my word for it. See for yourself: Galleries are free, and they love lookie-loos like you.

Urs Fischer’s The Lock, at the New Museum of Contemporary Art this fall. Image courtesy of the artist; Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York; Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zürich; and Sadie Coles HQ, London.

Eric Doeringer’s Sol LeWitt-Wall Drawing 118. Image courtesy of the artist, Creative Thriftshop, and Dam Stuhltrager Gallery, New York.

The Bruce High Quality Foundation’s Explaining Pictures to a Dead Bull. Image: Tyler Coburn/Courtesy of the artist and Harris Lieberman, New York.

A still from Sterling Ruby’s The Masturbators. Image courtesy of X Initiative.

Dasha Shishkin’s Afraid of Certainty. Image courtesy of the artist and Zach Feuer Gallery, New York.

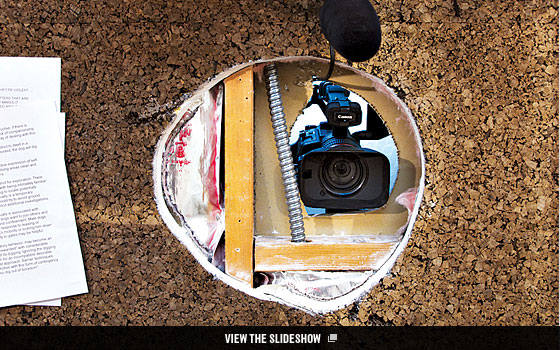

Enactment of Duke Riley’s Those About to Die Salute You. Image courtesy of the Queens Museum of Art.