In 1996, Griffin Dunne was getting ready to direct a film called Addicted to Love, with Meg Ryan and Matthew Broderick, and he met with a young production designer named Robin Standefer. He wanted the movie to have some of the cartoonish nineteenth-century-industrial qualities of the films of Marc Caro and Jean-Pierre Jeunet—who made Delicatessen and The City of Lost Children—and Standefer, understanding immediately what he was after, took Dunne to a prop house in Brooklyn that “specialized in things like turn-of-the-century gynecological equipment and bottles of unguents and spindly old wheelchairs,” Dunne recalls. “I could have lived there.”

In a way, he still does. He loved the loft that Standefer and her then-boyfriend, art director Stephen Alesch, had created for the French ex of Meg Ryan’s character so much that he wanted to live in it himself. “It was so hot-shit that, at the end of the film, I bought everything,” he says. “The rugs, the bed. I live with it today.”

He then hired the couple, who’ve since married, to do the production design for his next movie, Practical Magic, with Nicole Kidman and Sandra Bullock. Standefer and Alesch designed a three-story house that “looked like it had been there forever” and a kitchen somehow so profoundly satisfying that Dunne fielded queries about it afterward. (“You’re calling me about the stove, not the movie?”)

This is how these set designers began transforming the real world into something more pleasingly cinematic. Bullock, Ryan, and Broderick all “began circling,” says Standefer, wanting, like Dunne, to live in a set that didn’t have to be struck when filming ended. But nothing came of these conversations; there was always another movie to film.

Then, in 2002, Ben Stiller, who used them for Zoolander and Duplex (a film, appropriately enough, about the lengths New Yorkers will go to get the perfect apartment), asked the couple to think of building a place for him instead of doing another film. They’ve since designed four non-movie residences for the actor.

So they started a “buildings and interiors” firm called Roman and Williams (neither is a registered architect, though Alesch trained as one), named, with the same create-a-legacy ethic that has come to mark everything they do, after their maternal grandfathers. In 2004, in the midst of doing a Los Angeles house for Kate Hudson, they quit their rental in Silver Lake and moved back to the loft they owned in Noho.

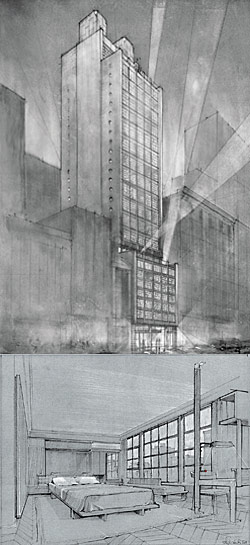

They got their big break that year when André Balazs hired them to work on the interiors at his meatpacking-district Standard Hotel, including the Boom Boom Room. After that was under way, they were hired to remake Philippe Starck’s haute-1988 lobby of the Royalton, followed in quick succession by a commission to design the interiors of New York’s Ace Hotel. As their careers took off, they moved on to entire buildings, including a new brick condominium on the corner of Elizabeth and Prince Streets so contextual it’s nearly impossible to notice, and a just-announced 30-story hotel on West 57th Street that breaks ground in January. They get fan mail from people who aren’t real-estate developers and sometimes, they say, they get recognized on the street. All the while, they’ve been steadily building a New York that many New Yorkers have always fantasized was the city they lived in. It’s heirloom design, prop houses for living. They’re not alone in this: Keith McNally and Taavo Somer have been creating prefabricated backstories for your dining pleasure for years, while architect Robert A. M. Stern has shown the profit and prestige to be had in faking the prewar in new condo buildings. But Standefer and Alesch are comfort-architecture stars.

“They create an environment where even though it’s new, it seems to have inherited a history to it, a preexisting world that goes on,” says Dunne.

“I don’t invent a lot,” Standefer, 46, says intently. She’s a careful, coiled talker, the sort who often repeats your name to make sure she’s holding your attention. “I like to draw from the familiar and find new ways to express them.” Alesch, 45, leaves her to do most of the conversational selling, while quietly pencil-hatching the corner of one of his meticulous sketches of the already-built ground-floor restaurant for the Standard (tucked under the High Line’s girders), carefully smudging it for the right effect. “The thing with Stephen and I, we don’t really like design that much. I want to say we’re almost anti-design. We think more about the narrative, more about the experience, and the spaces sort of accumulate out of that.”

This is how they work: She talks, he sketches; she’s a designer who loves structure, he’s an architect who loves minutiae. But on everything, they both have to agree. We’re sitting in Roman and Williams’ little conference room on Lafayette Street, a stack of matted photographs and plans between us. The wall behind Standefer is frosted safety glass, like from an old factory or a creepy state hospital, framed in iron, and the shelves to her right are filled with inspirational knickknacks: an aluminum office lamp, some glass vases, fossils. They recently signed a deal to make a line of furniture for that ultimate popularizer of the Mad Men look for the home, Design Within Reach. It won’t resemble something Charles Eames created to furnish a mid-century Utopia. They describe it as being inspired by “early modernism, before it became totally stripped down.”

“A lot of people misunderstand what they see as our nostalgic-ness,” says Alesch. “We love older things because they’re better made. But we’re not Luddites in the sense of, um, just filament bulbs or a big block of ice and a fan.”

“We love the unused,” says Standefer, pointing to a detail of a door in a photograph of the Elizabeth Street condo.

“It’s beautiful, right? It’s a beautiful flange,” agrees Alesch, referring to an interesting, but nonfunctional, metal lip.

“All the bricks are dead stock, too. No one’s used them since 1930,” says Standefer. “They were like, ‘You want to use those?’ And we were like, ‘Yes, please.’ ”

“Sourcing is a huge part of what we do.”

“Going to wood shops or factories, digging through back rooms.”

Theirs is a connoisseurship sensibility, a journey toward quality. And they see respect for the past as being something essentially moral. “We are trying to take a role in the growing-up phase of this country,” says Alesch. “You know, growing up in the seventies and eighties—fun moments, for sure, but a low point in the culture of the Earth, especially in construction.”

The couple can dig through the vast Brimfield Antique Show in Massachusetts to find, say, the perfect glass panels from a 100-year-old schoolhouse to use as the ceiling for the private dining room of Andrew Carmellini’s new restaurant, the Dutch. Or they can design, for Cole Haan, the office-shoe division of Nike, a new store in Soho that “has some level of authenticity” and can “help customers to understand the history” of the brand, says Standefer.

“It’s taken twenty years to kind of shake those dumb, hippie seventies things of ‘never look back, only forward’; ‘history is meaningless’; ‘no regrets,’ ” says Alesch, who apparently has some issues with Maoism that he’s taking out on the drafting table. “We kind of feel like we’re just this first group of people to say there’s nothing wrong with looking back and moving forward …”

“Some architects were like, ‘Where did you copy that from?’ Really juvenile statements.”

“Concurrently,” says Standefer.

“It’s not like if you look back, you’re going to be stuck in a top hat and driving a Model T,” Alesch continues (although when you look at the Dickensian barista costumes in the coffee bar at the Ace, you might wonder if that’s the case). “My love of traditional architecture came from growing up in places like Arizona, where there’s, like, 7-Elevens and gravel. There was nothing to rebel against—anything old had been bulldozed. Even in L.A., there’s all this rebellion but no background. And I always said I want to help build that background,” he says. “I love rebellious artists, nihilist artists. But I decided I’m going to help build the new background that they can kind of terrorize.”

He was born in 1965 and started his life outside Milwaukee. “But when I was 2, my mom bailed on the house and, with my brother and me, moved downtown and kind of teamed up with the Black Panther movement. It was pretty intense and scrappy there then. My brother and I were the only white kids in our entire school.” In 1973, he and his aunts moved to a New Age community in California. (“The blonde sisters in the station wagon with all the kids and the little black babies driving to California. I mean, you have to have the vision,” says Standefer.) One of his mother’s sisters married the guru, Torkom Saraydarian, and Alesch didn’t have to go to school, “and when I did go,” he says, “I was sent home because I was so filthy.” Then they moved to Sedona, “because of the vortexes,” in 1982.

“Things need something to react to,” says Standefer, who grew up on the hippie-era Upper West Side. “But suffice it to say that I was with my parents in 1969 when they were smoking hash with a rug dealer in Morocco. It sort of goes on. There were always parties and traveling and hanging out with musicians and people at the house— ”

“We had no punishment,” says Alesch.

“No punishment; it was just ‘free to be you and me,’ ” says Standefer. “My mother was a model, young, and then stopped working. My dad trained dogs. Nobody did much work.”

Alesch and Standefer, unsurprisingly, are workaholics, with a firm named after his grandfather Roman, a painter, and her grandfather William, a jeweler. “Hardworking guys, working class,” says Standefer. “Old school, money under the mattress.”

“And our parents were like, ‘You want to be like them? They’re the ones that kicked my ass,’” says Alesch.

After André Balazs “jump-started us” with the Standard job, says Standefer, “we just got swept up in the boom. Everybody was building, everybody dug us.” Today, even though not much else is getting built, they are so busy, they’re turning down work. Consequently, they’ve come to define the retro look of the Great Recession.

Standefer is on a mission to create the familiar, even if it comes at the expense of someone else’s heritage. When Roman and Williams overhauled the famously abstract and hard-edged Starck lobby in the Royalton, they turned it into something groovy and comfortable, but not necessarily startling. “I hate to say it, but if you remember walking into that lobby before we redid it,” says Standefer, “it was terrible. From a pure physical point of view. I’m not talking about stylistically; it just ached, terribly.” (Starck wasn’t happy, complaining to the Times: “I think if you are lucky enough to own an icon, you shouldn’t kill the icon.”)

They had little use for the ache of the new. “I don’t want to be tabula rasa,” she says. At the same time, they don’t want to be known for a particular style either: Roman and Williams will do whatever they’re hired to do, whatever makes sense for the film the client sees himself (and his future customers) in.

This collaborative ethic is why Balazs hired them to work on the interiors of the Standard—that retro-monument to the exemplar of tabula-rasa modernity, Brasilia. It was itself designed, by the Polshek Partnership, to look like it had been atop the High Line for decades. Balazs’s friend Griffin Dunne recommended them. “We don’t look to designers to provide creative direction,” says Balazs. “What was so nice about Roman and Williams when I met them: They had no style then. They’d basically done a kitchen or two and, other than that, a film set.”

Which isn’t exactly accurate, but then Balazs is a bit annoyed at Standefer and Alesch for writing an open letter to the website Curbed.com arguing about who gets to claim credit for the Standard’s interiors—Balazs’s longtime collaborator Shawn Hausman or Roman and Williams. (“Shawn dropped in on only a few meetings over the five-year design process, never visited our offices or met with us privately, never put pen to paper on this project and never approved or corrected any sketch or working drawing,” they wrote. “Therefore, he should not be given credit for the design.”) Balazs dismisses this, saying loftily that “the hallmark of a good collaborative team is that you almost forget who originated the idea.”

The most successful of the interiors is the Boom Boom Room, the Standard’s penthouse party chamber. The mood there is very Nude for Satan, according Alesch, referring to the 1974 Italian B-movie. Balazs, they say, wanted it to look like the inside of a Bentley. Ultimately, its visual ethos was grounded in the groovy corporate glamour of Warren Platner (“White turtlenecks and gold necklaces,” says Alesch), who designed the interiors of Windows on the World, which also opened in the early seventies. And the Boom Boom experience, especially looking south to the harbor, is not unlike the old Windows. Balazs says it was supposed to evoke the Rainbow Room.

Even as the Standard was going up, Balazs’s former business partner, Andrew Zobler, had bought an old SRO with partners on 29th and Broadway with the idea of turning it into a hotel. He wanted to bring in the people behind the Ace hotels in Seattle and Portland to run it and had asked the Ace team whom they’d hire to be the architect. Alex Calderwood, one of the Ace’s founders, called Serge Becker, one of the people behind the restaurant La Esquina, who told him to call Roman and Williams. As it turns out, among the pictures the Ace founders had on their “inspiration wall” was a photograph from a magazine of Alesch and Standefer’s bedroom.

Unsurprisingly, Calderwood shares Roman and Williams’s quasi-academic mystical design language. “Narrative is a very, very important word both for us and them. We like to explore and celebrate a narrative in terms of an item or object,” he says. “We share a mutual interest in kind of manufacturing techniques and materiality and an appreciation for a sense of history but not being slavish to an absolute re-creation. It hopefully feels like it was collected and curated over time, has a sort of residual feeling.”

Zobler is just happy that, even if it’s an accident, the Ace is the lobby du jour. “I think their style fits perfectly into the post-recession reality,” he says. “Comfortable and inclusive. It’s not cold or like a nightclub. It’s inviting.”

Which isn’t to say Roman and Williams always gets respect from their peers. One prominent city architect allowed that they were “contextual” but refused to say more, not wanting to “resort to a string of verbal abuse.” Another, Enrico Bonetti, whose firm, Bonetti/Kozerski, works in the minimalist style that was until recently popular for luxury projects, notes that “it’s not strange that in times of depression, people look back to the past.” Still, “I’m a little jealous that now they’re everywhere.”

Of all their projects, the one that is most completely theirs—an idealized back lot New York to live in—is 211 Elizabeth Street, in Nolita. It was conceived during the height of the boom, when “there were a lot of glass towers going up,” Standefer says dismissively.

“They’re all caulk, those glass buildings,” says Alesch.

“A house of caulk. And we said, ‘We want to do a building that’s all masonry, that’s got big black wood windows.’ ”

The developers were like, “ ‘That’s boring,’ ” says Alesch. But the couple persevered, arguing for the city as it’s always been—only more rigorously so.

“This is what we do all day: design and convince,” says Standefer. “And it ends well. The world changed; there was this huge crash and burn and then all of a sudden Elizabeth Street was like this beacon of quality amidst the condo boom … the developers actually got fan mail. ‘Thank you for not building a piece of crap.’ ”

“There are some architects and some sort of unthoughtful people that were like, ‘Well, where did you copy that from?’ Really juvenile statements,” says Alesch. “It’s like, ‘No, it wasn’t cut-and-pasted any more than any building in New York City.’ It’s the highly trained architects who have the least ability to see the difference between buildings in New York and tend to generalize that they all look the same.”

“We were happy to see it almost disappear,” says Standefer. “We had a fantastic meeting the other day, a big corporate meeting, and the people were like, ‘Wasn’t that always there?’ Which we consider a great compliment.”

See Also:

The Fall 2010

Home Design Issue