The amazingly lifelike doll pictured opposite arrives in a box, in a gauzy chemise, with her own set of genitalia, a tube of lubricant, and an engagement ring. For those who order her, there’s no question of how to exploit the various possibilities. For artist Laurie Simmons, it took a little longer. “That she was a sex doll was secondary to the fact that I had finally found a Tales of Hoffmann, life-size doll that I could work with,” says Simmons. “I don’t want to deny that it is used as a masturbation tool. I just chose not to address it. I am amazed that a doll made for this purpose could be rendered so exquisitely. The lines of the body are so refined; it’s a beautiful sculpture.”

Simmons began by dressing the doll in ordinary clothes—a bridal gown, swimsuit, down coat—then positioning her around her Connecticut home as an Everygirl, a kind contemporary sister of the Lonely Doll of Dare Wright’s fifties children’s book. The result is “The Love Doll: Days 1–30,” a series of large-scale, full-color photographs, which is the inaugural show at Jeanne Greenberg Rohatyn’s renovated gallery, Salon 94 Bowery. It also marks the first time Greenberg Rohatyn has represented Simmons. “I came to her studio and saw this body of work, and I said, ‘I have to show this—it’s so exciting and weird and profound and beautiful,’ ” says Greenberg Rohatyn, who will seduce viewers into her space with a traffic-stopping, ten-foot-wide video of the doll as a geisha.

Simmons—who is married to the painter Carroll Dunham and the mother of two daughters, including Lena Dunham (writer-director-star of Tiny Furniture, in which Simmons appears)—has always used props in her work: miniature figurines, male ventriloquist’s dummies, objects embellished with mannequins’ limbs. Her pieces are frequently given “a complicated feminist read,” which is not, according to Simmons, her primary intention. “My work is not a manifestation of a political thought. It is almost one hundred percent intuitive.”

The “Love Doll” series notably lacks the sense of nostalgia informing Simmons’s past work, which was due, in part, to the materials she used: quirky props often staged in retro-looking settings. The sex doll has, in effect, liberated her. “I have finally found a full-scale, articulated doll that isn’t really doll-like. I can shoot in the contemporary world and in the present moment,” she says. “This is definitely the closest I’ve skirted to realism. Even I’m confused [by the images] sometimes.”

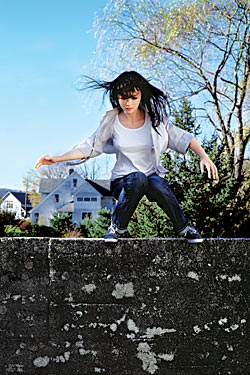

Day 25 (The Jump) is one of only two shots set outdoors. “For most of the pictures, the doll was placed around the house, and there was something essentially passive and feminine about it,” says Simmons. “It was really hard to figure out how to activate it.” To transform the doll into a “Ninja girl in sneakers,” the artist borrowed Keds from her assistant and clothes from her daughter Grace. “I went out with the idea of turning her into a tomboy, which is what I was when I was a kid.”

For both Simmons and Greenberg Rohatyn, the “Love Doll” images are an artistic leap forward. “Laurie has gone from using dolls as a kind of plaything to creating something that we have real empathy for—the doll is empowered, free. She has her own integrity,” says Greenberg Rohatyn. “The life-size scale changed everything. It isn’t child’s play anymore. Laurie has really breathed life into her.”

The Love Doll: Days 1–30

Laurie Simmons.

Salon 94 Bowery.

Through March 26.