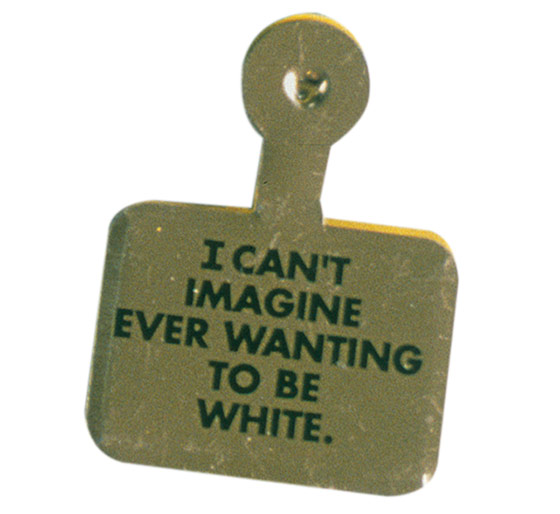

Twenty years ago, at the 1993 Whitney Biennial, fault lines opened up and the ground shifted. What was quickly labeled the “politically correct” or “multicultural” Biennial contained little painting, which had dominated the past few installments of the show. This time, the exhibition was full of installations (Charles Ray’s full-size replica of a bright-red toy fire engine; Coco Fusco in a cage in the courtyard, costumed as a Native American), site-specific sculpture, and video (Matthew Barney as a genital-less satyr). It was mostly art by unknowns, too: Setting aside the video-and-film program, about 30 of the 43 artists were in the museum for the first time. More than 40 percent of the participants were women, quite a few were nonwhite, and a generous amount of the work was about being openly gay. One of the exhibition’s admission buttons, designed by artist Daniel J. Martinez, read I CAN’T IMAGINE EVER WANTING TO BE WHITE.

People went batshit. Contempt was everywhere. Robert Hughes saw strains of Stalinism. Peter Plagens wrote that it had the “aroma of cultural reparations.” Referring to the Biennial’s one African-American curator, Hilton Kramer hissed, “There is a certain awful logic in having Ms. [Thelma] Golden on the curatorial team.” New York Times chief critic Michael Kimmelman wrote “I hate the show,” saying it made him feel “battered by condescension” and that it treated art “as if pleasure were a sin.” Oh, my. Joining the pleasure police was Peter Schjeldahl, whose Village Voice review was titled “Art + Politics = Biennial. Missing: The Pleasure Principle.” One notable exception was Roberta Smith, in the Times, who called it “a watershed.” She and I had been married eight months earlier.

And me? I wasn’t writing a regular column then—I was still making my living as a long-distance truck driver, writing on the side—and I didn’t review the Biennial. But I did, in a short Art & Auction story, say something like “The fact that everyone hates this show made me like it and know that it’s important.”

In retrospect, it’s amazing to see how hung up everyone was. These artists were against not beauty but complacency; they were for pleasure through meaning, personal meaning. They saw that the stakes had risen by 1993, and they were rising to meet them the best they could. Of the show’s 82 artists, about half still have significant careers. That’s an exceptionally high percentage, especially considering how many were unfamiliar figures before then. A few 1993ers—Janine Antoni, Pepon Osorio, and Fred Wilson—are now MacArthur winners. Robert Gober, Bill Viola, and Wilson have each represented the United States in the Venice Biennale. It’s fair to call the 1993 Biennial the moment in which today’s art world was born.

So what happened?

Generalizations are always faulty, but two stories dominated the eighties art scene. First, painting returned. Big paintings, about painting’s history, by men who wanted to enter art history. My wife called these guys “the barrel-chested painters” after seeing a book jacket picturing Julian Schnabel, Markus Lüpertz, and Jörg Immendorff with shirts off and pecs out. The second story was “Pictures Art”—a vogue for images, sometimes painting but usually photography, made mainly by women, much of it skeptically critiquing art history or commodity culture. It was probing and cerebral, but Pictures Art, too, talked primarily to insiders. It was more about the canon than about the larger world.

The art that emerged in the early nineties could not have been more different. It came from all over the globe, and it wasn’t as painting-centric or flashy. It was being formulated in small groups fed up with overcommercialization. Many of these artists were influenced by conceptualism, feminism, theory, and Pictures Art, but they turned away from making work about art, commodities, or pop culture. Initially their work got more intimate, eccentric, obdurate, pressing, and personal. Reviewing the show, Kimmelman described “one sensationalistic image after another of wounded bodies, heaving buttocks, plastic vomit, and genitalia.” That collective vomiting was a massive blast of new energy.

The artists who emerged in the generation that began here made work that was weirder, less hangable, and derived more from idiosyncratic impulses. Nan Goldin unveiled pictures of the people, dying and dead, whom we’d met in her previous decade of work. In 1993, Charles Ray showed one of the best sculptures of that decade or the next, Family Romance, an uncanny rendition of a family of four standing stark naked, all about chest height and the same size. It still shoots Freudian sparks. In these years (though not at the Biennial), Hanna Wilke showed her tremendous last-act images of herself dying of lymphoma: She was a gorgeous gorgon angel of death. Paul McCarthy, almost forgotten by 1993, exhibited a large animated mannequin of a man having sex with a goat; it was the first of many greater, grosser installations. Artists were capturing the ways that identity and the body, be they political, sexual, physical, psychological, or doomed, would become central themes of the decade. Central themes because they were necessary themes. Identity politics (or “political correctness,” if you didn’t like it) was becoming a dominant piece of the national conversation, as it still is twenty years later. The country was becoming more diverse—a place that could elect Barack Obama as its president—and some embraced that new reality in order to move forward; others reacted against it. The Biennial was on the side of the future, and still is.

It shames me to admit now how challenging and difficult I found some of this work at the time. To put it plainly, I was against it before I was for it. John Currin’s exaggerated realism and his twisted women kept me off balance, never knowing if they were sincere or ironic or some new emotion. Wolfgang Tillmans’s stunning large-scale pictures, being shown for the first time, were so offhand I failed to see them as art. I didn’t know what to make of Felix Gonzalez-Torres, either, and his work is key to the era. Poetic, formal, pensive, and subversive all at once, the sculptural stacks of paper that people were allowed to scavenge and piles of wrapped candies that visitors could eat were rife with allusions to temporariness, what it means to give things away for free, and art’s fragility and renewability and ability to transubstantiate.

Every movement that slays its gods creates new ones, of course. I loathe talk of the sixties and seventies being a “Greatest Generation” of artists, but if we’re going to use such idiotic appellations, let this one also be applied to the artists, curators, and gallerists who emerged in the first half of the nineties. They, too, changed art, for the better. Cady Noland’s sculptures and installations pushed my ideas about art as far as any in my lifetime. Noland is the crucial link between eighties appropriation art, like Richard Prince’s, and much that has followed. She arranged beer cans, chain-link fences, pierced pictures of assassins, and detritus willy-nilly into configurations that only later did I grasp as being as formally and politically powerful as, say, Gerhard Richter’s paintings of German statesmen. It pains me that she has more or less absented herself from the art world. And then there was Matthew Barney, with his wildly colored, highly complex proto-narrative videos, showing himself moving through space like some mythic enzyme through the collective body. From the beginning, I reveled in his work. (Currin, however, still freaks me out.)

That spring, Friedrich Petzel, then a director of Metro Pictures, told me he was about to open a gallery in his Soho loft-apartment. He said, “I have no idea how I will make any money.” He eventually figured it out, in Chelsea. So has Gavin Brown, then a director of 303, where he used to sit at his desk alternately sleeping and yelling at people. In 1993, Brown organized a show of the unknown painter Elizabeth Peyton in room 828 of the Hotel Chelsea. Maybe 90 people saw it, by Brown’s estimation. (One visitor later told me he had sex there.) It reminds me of that saying about the Velvet Underground’s first album—that only a few thousand people bought it, but every one started a band.

For the artistic class of 1993, smallness and being homemade were not problems. They were solutions. There wasn’t much money around—all we had was the ambition and desire to make something special happen, and it did. A new, more open art world came into being. Within a few years, money noticed, and over the past decade, some of these nineties dealers turned themselves into selling machines. Something special happened, but something else got lost along the way. Nineteen ninety-three matters because it looks like numbers of people are starting to pick up the pieces and put them together in new ways again. It’s time to pay attention.