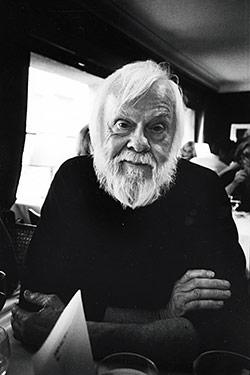

John Baldessari, the 79-year-old conceptualist, has spent more than four decades making laconic, ironic conceptual art-about-art, both good and bad. His style is familiar and recognizable, wry and dry: It usually incorporates a photo or grid of pictures, often black-and-white and grainy, with the vibe of a seventies issue of Artforum; text of some kind; a found object placed casually; a video or maybe a newspaper clipping or some other element taken from popular culture. The approach is hugely influential, setting the precedent for interesting artists like Cindy Sherman and David Salle. In a sense, Baldessari imagined a large circular room with a hundred entrances and exits. Thousands of artists could go through, and did. After a visit to the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s retrospective, you’ll see that Baldessari’s children have overrun Chelsea.

And that’s the problem. Even a former student like Salle admits that “at least three generations of artists” doing “dumb stuff … is largely John’s fault.” Baldessari’s interesting niche bewitched too many people, creating a hackneyed academy of smarty-pants work that addresses the same issues in the same ways, over and over, just the way Baldessari and others of his generation did 40 years ago. Baldessari has talked about how a painter called him “one of those ‘write-about’ artists,” and indeed he is: Critics and curators love to pick over his cerebral creations.

When he started out, in Southern California in the sixties, Johns, Rauschenberg, Cage, Pop, and minimalism ruled the roost, and that roost was in New York. Vito Acconci, Richard Serra, Joseph Kosuth, Mel Bochner, and Robert Smithson were beginning to make post-minimal and conceptual waves here. Painting was pronounced dead (again). So was art in general. Not much was allowed from outside this magic, mostly male circle, and things made in California seemed superfluous to this cliquish clan. But that coastal divide provided a canyon-size aesthetic opening, freeing up artists like Ed Ruscha, Bruce Nauman, Paul McCarthy, and Baldessari, all of whom developed styles vastly different from those in the East. Baldessari’s art was never as unnerving or revealing of secret psychic structures as Nauman’s. Nor was he as intelligent or as visually original as Ruscha, as darkly poetic as Acconci, or as relentless as Serra. Yet he marked out an infinitely inquisitive territory all his own.

That said, I don’t care for large chunks of his work. For me, it falls into two distinct eras. The early work, when he was unsystematically finding his way, lasts roughly from 1962 to 1980. I admire this period the most, sometimes a lot. But after 1980, when he went from small and uncertain to big, clunky, and fragmented, the results get formulaic and optically awkward. The multipart works, usually involving photographs, dots of color over faces, cutout shapes, and irregularly hung framed pictures, strike me as mannered. I consistently dislike this stuff, sometimes a lot, and it fills the last four or five galleries of the Met’s show.

Linger instead in the early rooms, which contain some mini-masterpieces. In these works you feel the sweet spirit of curiosity, the pleasure of things at the edges of art. Baldessari’s titles often tell you what you’re looking at; it’s his weird way of investigating the spaces between a work and its name while also attempting to reach wider audiences. The artist has said that he was “taking that information that’s already there in the culture and pushing it slightly askew.” Sometimes when he does this, a new light shines. I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art, a work every artist ought to be required to make once in his or her life, is a short video in which Baldessari repeatedly writes that sentence until he fills a piece of paper. This is pedagogy, punishment, and promise—the work of a prisoner and a preacher of art. (And it’s not boring.) Another video finds Baldessari singing in his flat voice, to melodies like “Yankee Doodle,” using the artist Sol LeWitt’s manifesto “Sentences on Conceptual Art” for lyrics. My mind did lovely loop-de-loops between thinking, listening, singing along, and puzzling; I also saw this as a direct bridge to Louise Lawler’s marvelous recording of bird calls using only the names of male artists.

A number of Baldessari’s text and image paintings tickle and titillate, particularly a series in which he commissioned other artists to make paintings that said things like a PAINTING BY ELMIRE BOURKE with a nondescript photo-realist rendition of a finger pointing at an object. Another work, in which he uses only text, simply says EVERYTHING IS PURGED FROM THIS PAINTING BUT ART, NO IDEAS HAVE ENTERED THIS WORK. I love experiencing the toggle point here between joke, philosophy, contradiction, and paradox.

There aren’t many paintings to see. That’s because, in 1970, in a state of artistic dissatisfaction, Baldessari took nearly all of them to a mortuary and had them burned. He poured some of the ashes into a book-shaped urn, titling the work Cremation Project, and it’s on view at the Met. Judging from the few canvases that remain, Baldessari had it in him to be a very good painter. You can see him studying Jasper Johns especially. In one work, he pulls off an incredibly rare act of aesthetic clairvoyance: God Nose, from 1965, is a stark blue image of a disembodied proboscis floating on a blue ground with a little white cloud. It looks almost exactly like a number of works involving disembodied, floating facial features that Johns started making in the late eighties.

There’s one Baldessari work I genuinely love and would like to own, maybe because of my midwestern roots and love of driving alone. The backs of all the trucks passed while driving from Los Angeles to Santa Barbara, California, Sunday, 20 January 1963 consists of a grid of 32 small color photographs depicting just what the title says. It was his version of a Dan Flavin: drop-dead simple, self-explanatory, and singular. In this wonderful piece I sense the openness of art, Baldessari’s receptivity, and the sight of an artist exercising what D. H. Lawrence once called “insatiable American curiosity.”

John Baldessari: Pure Beauty

Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Through January 9.

E-mail: jerry_saltz@newyorkmag.com.