As I made my way through “On Line,” the austere, stridently dogmatic, sometimes revelatory exhibition “about line” at MoMA, I found myself thinking, Someone please wake me when the seventies are over! In the empire of curators, the sun never sets on the seventies. It is the undead decade.

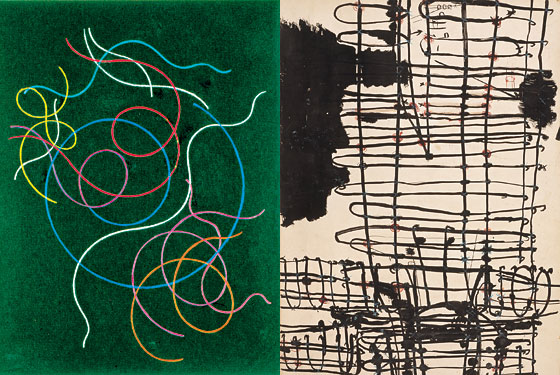

MoMA’s chief curator of drawings, Connie Butler, and guest curator Catherine de Zegher claim their show goes “beyond institutional definitions” of drawing and that it maps an alternative history. I wouldn’t go that far: “On Line” is well-traveled post-Minimalist territory, albeit with some wonderful loans and work from MoMA’s collection (naturally, it opens with Picasso; at MoMA, all modern art springs from the fountainhead of Pablo). The themes are familiar—ideas about grids, systems, performative procedures, and the like—which means that even the most recent pieces look as if they could have been made during the Nixon administration. The one nice thing about this purified retelling? We’re spared Surrealism.

“On Line” is worth it, though, for the women. Take the 1897–1899 film clip of pioneer modern dancer/burlesque performer Loie Fuller, whose whirling arabesques of fabric remind you how important dance and movement are to modernism. (Her undulations are infectious by association, turning the curvaceous lines in Frantisek Kupka’s nearby drawings into sexy round rear ends.) Nearly half the artists in the show are female, many of them usually relegated to the margins. The work of Atsuko Tanaka, Yvonne Rainer, Maria Helena Vieira da Silva, and especially Lyubov Popova looks so good I’m wondering why we’re not seeing solo shows. Sophie Taeuber-Arp’s crisp, colored drawings from the 1940s predict Agnes Martin and Ellsworth Kelly. And her husband Hans’s cord mixed-media works, hanging nearby, brought back to me his importance in championing chance, eccentric materials, and the monochrome.

I wish “On Line” had more of the unpredictable, shocking spice of life found in the unfinished charcoal by Piet Mondrian: You can see him looking for ways to move lines one fraction of a millimeter at a time. It made me wonder at the absence of Charles Ray, whose Ink Line has real life, or the visionary kingdoms in the drawings of Martin Ramírez, or Giacometti, who showed that putting a mark on paper is a way of not going gentle into anything. The curators have shunned narrative and cartoonier work that might have folded the line, freed it from the frame, or danced it in an uncanny direction. What we’re left with is its most rigid definition.

On Line: Drawing Through the Twentieth Century

Museum of Modern Art.

Through February 7.

E-mail: jerry_saltz@newyorkmag.com.