I t couldn’t happen today, not in such an expensive and security-conscious city. But in the early seventies, Gordon Matta-Clark made transformative, transgressive art out of New York’s desolate corners. Without permits or any official support, the former Cornell architecture student hacked into the walls and floors of derelict buildings (of which there were many), turning shadowy wrecks into light-filled sculptures. “I don’t like the way most art needs to be looked at in galleries,” Matta-Clark once said, “any more than the way empty halls make people look.” He made art out of parts of the city nobody else wanted—literally, as when he bought up many of those leftover slivers of real estate that can exist between lots. You couldn’t acquire much of his work; it was clandestine public art, of a sort you might not notice if you weren’t looking.

It was nearly all ephemeral. His most important works survive only in photos and on film, with the odd remnant poking out here and there. In fact, not just the buildings but the entire neighborhoods where he worked—Soho, the meatpacking district, even the South Bronx—are vastly different places today. (Matta-Clark himself vanished early, too, dying at 35 in 1978.) But though his work is largely invisible, he is not: The Whitney’s Matta-Clark retrospective opens February 22, and we looked at what’s left (and what isn’t) of several of the artist’s projects, from an utterly transformed Soho storefront to a lot in Queens that looks as drab as ever.

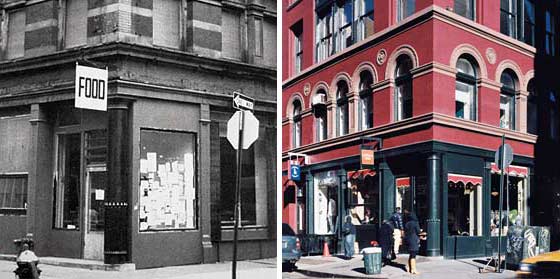

Food (1971)

You can’t have an artists’ enclave without an artists’ hangout, so Matta-Clark co-founded this restaurant, at Prince and Wooster Streets, with artists, students, and dancers Carol Goodden, Tina Girouard, Suzanne Harris, and Rachel Lew. There, he blurred the line between restaurant and performance space, composing memorable menus (one dinner consisted entirely of bones) and inviting artists such as Donald Judd and Mark di Suvero to serve as guest chefs. A film chronicles a day in the life of the restaurant, from an early-morning trip to the Fulton Fish Market to the baking of the next day’s bread. Food survived into the eighties; today, those boarded-up windows on the second floor inspire mostly real-estate longing.

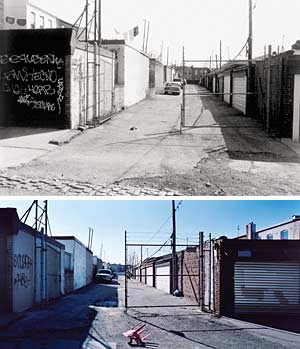

“Fake Estates” (1973–1974)

At a public auction, Matta-Clark purchased tiny orphaned bits of land created by surveying and zoning irregularities, some as small as one square foot. The Ridgewood plot pictured here—the work is called Reality Properties: Fake Estates–“Long Alley” Block 3398, Lot 116—measures 32 inches by 350 feet, runs down this alley, and cost him $25. “The description of them that always excited me the most was ‘inaccessible,’ ” the artist said. Matta-Clark died before doing anything beyond the paperwork stage; after his death, the city reclaimed all the land. In 2005, Cabinet magazine organized “Odd Lots,” a show at the Queens Museum and White Columns that allowed visitors to take a bus tour of the “estates.”

…Plus Three That Are Gone.

Splitting (1974)

Matta-Clark may be best known for his “building cuts,” in which he sliced structures like loaves of bread. This house in Englewood, New Jersey, was split in two, over four months of jacking and tilting. Manfred Hecht, who helped out, said, “It was always exciting working with Gordon—there was always a good chance of getting killed.” The house’s corners are now in the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, but the rest is gone— it had been chosen because it was slated for demolition anyhow.

Day’s End (1975)

Matta-Clark cut five openings into the decrepit shed of Pier 52, calling it a “basilica” with a “rose window” (a bean-shaped hole facing the sunset) and illuminating a spot known for seedy nocturnal misbehavior. It was all done illegally—he later said, “I had no faith in any kind of permission … there has never, in New York City’s history, with maybe one or two minor exceptions, ever been any permission granted to an artist on a large scale”—and once the city got wind of the project, Matta-Clark ended up leaving the country to avoid arrest. (The pier today is a flat slab, with no superstructure.)

Jacks (1971)

In a performance organized by Alanna Heiss (who now runs P.S. 1), Matta-Clark and other artists took over the arches under the Brooklyn Bridge, sharing turf with homeless men, gang members, and heaps of junk. For Jacks, Matta-Clark hoisted the wrecked cars that had been dumped there, creating makeshift shelters that looked to have been dropped by a vacationing Kansas tornado. At the finale, he roasted a pig on a spit and handed out free pork sandwiches.