I am a Marshian, from Bacchus Marsh, Australia, a place where the commonly accepted rules of alternate-side parking and literary publishing have never applied. As a 64-year-old New Yorker, I still carry the Marshian world inside my head, a world where you never expected to be published outside your own backyard, where $10 was what you were paid for a story in a magazine. Melbourne was just 33 miles away. Of this splendid city, Ava Gardner is reputed to have said, “If the world needed an enema, Melbourne would be the place to give it.” Many of us who came to live in Melbourne thought she maybe had a point.

We were wrong, of course. Melbourne was ideal—there was something almost pure in writing literature in a time and place where you never expected to make a dime, something glorious and futile in attempting to make Australian literature when, as everybody in London knew, Australian literature did not exist. Writing after work at the kitchen table, I was risking nothing except my sentences. No one knew I was there. There was no one to network with or suck up to. There were not 567 agents and 5,345 editors who imagined, rightly or wrongly, that their lives depended on discovering my unknown self, running me to ground at my Olivetti Lettera 24, breaking me through, publishing me too early, and losing interest when my second book did not fulfill the quirky promise of the first.

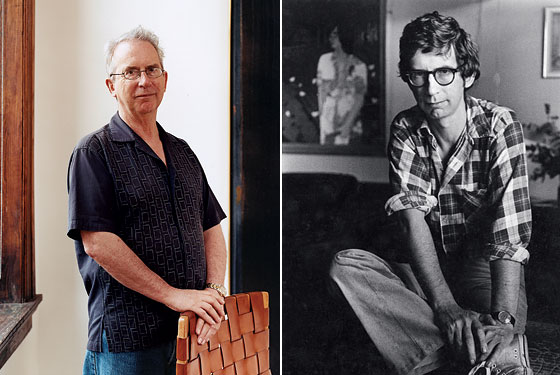

There was just one literary agency in Australia in 1962, but I didn’t know what a literary agent was. As for an M.F.A. in creative writing, I’d never heard of such a thing. Denied these distractions, all I could do was write. So by the time I came to Manhattan in 1990, I had turned myself into a freak who lived by writing literature. It had taken almost 40 years, but I arrived in the Village as if by C-section, having escaped the long birth trauma, already knowing that Binky Urban was my agent and Sonny Mehta my publisher. I had won the Booker Prize. I had no experience of being a young, ambitious writer in New York.

However, every Tuesday night I sit in a room at Hunter College with twelve students, and we talk about their work, or the sentences of Bruno Schulz or Henry James, and we try to figure out how it all works, not the business of the business, but the business of this sentence, this story, in language I do not doubt I would have once judged pretentious. And in doing this I am part of a strange New York fantasy that all or some of these twelve people will one day, perhaps next week, perhaps in twenty years, be freaks like me. At the same time, we all know it cannot be everybody who will live from making literature. And we are incapable of guessing—me as much as anyone—who that will be. One can never anticipate who will bob up on the front page of the Book Review and how long it will take to get there. The elegant, inventive Darin Strauss? My God, he was my student years ago.

At the same time, sitting in the windowless neon-lit enclosure of room 1243, I am thinking that there is no worse place than New York to be a young writer. In my secret heart I believe they should not be here at all, but in Melbourne in 1961 when the bars closed at 6 p.m., there were three channels on TV, and the gas stations shut on Sunday. Who needed Yaddo or MacDowell? This was a perfect place to write.

I look around the familiar faces in room 1243 and imagine I can see the toll it takes to be a young unpublished writer in this town. How hard it is to make a living, pay the rent, have a relationship, write a book.

However, New York is the great white way, the red-hot center, the blue light on the deck that draws the talent in from Great Forks, North Dakota. You come to make your name. You go home to your fifth-floor walk-up, fall asleep over your own story, which is due in class tomorrow, try to change your shift at Starbucks when you know the manager is an asshole who will punish you till death.

It is not all bad: You get a sliver of the Chrysler Building from your bathroom window, and you know that Toni Morrison is out there somewhere, and Salman Rushdie. You think you spotted Don DeLillo at a reading, but how could you speak to him and what would you say? “I’m a writer. Please help me”? You ask Kathryn Harrison to sign your book and you would have talked to her if that huge, asthmatic book collector hadn’t shoved his ass right in your face. Is that really you, eating Doritos and watching that limo waiting for Julian Barnes outside the 92nd Street Y?

And also, most of all, are you even talented? Obviously not. You have spent a whole semester rewriting twenty pages of a thing you have come to hate.

My Hunter students do not ask when the agents will visit. They are there, I tell them, to be writers. Everything else will follow. But who can say they won’t get the fabled six-figure advance in the end?

And who would dare suggest they divide this number by the three or four or five years it took to earn it?

And would it stop them anyway?

And here is what seems most insane—young and not-so-young writers take out student loans to get M.F.A.’s in creative writing. This does not add up. I once taught in the M.F.A. program at Columbia, and so I know the extraordinary gifts that student debt can confer. But the Marshian in me says it’s impossible to start a life committed to literary fiction when you are $60,000 in debt. The very size of the loan assumes there is a market, a business to go into, a living to make. But the hard truth is that only a sucker writes literature with the intention of making money. This was so obvious in Australia in 1961, you never needed to say it. Today, when people seem to be breaking through all around you, it might be good to bear in mind that the only reward you can rely on is in the work itself. And, of course, they do know that. A while ago, I went down to Strand with my then 13-year-old son and we were, of course, selling books and we watched the buyer separating the sheep from the goats, without understanding which was which. When the judgment was made, he pushed back at us a pile of really good novels. These, it turned out, were the goats. I said, “But surely you can sell Rohinton Mistry.” And he said, “We don’t need fiction.” And I thought, Where am I?

And I thought, quoting Beckett to myself, Imagination Dead Imagine.

But those twelve students sitting round the table have to forget way bigger things than money. In particular, they must forget that they’re walking out onto the same field as Proust, Joyce, Woolf, Conrad, Austen. This should be enough to stop anyone. Of course, it never has been.

And I, for some insane reason, have ended up caring about their lives. Frankly, I should be worrying about my own book, and yet here I am fretting about how I can make it worth their while to be in New York.

So that student over there, the one who arrived from San Francisco, is now working as a research assistant with Jonathan Franzen. He’s the recipient of a Hertog Fellowship, and he’s by no means the only one. Indeed, there will be eight this year.

And there is A. working for Toni Morrison, and V. working with Salman Rushdie. And C. who went to work with Richard Price and found him a psychic and a haunted house on the Lower East Side. E. researched for Siri Hustvedt. G. worked with Patrick McGrath and collected information on spinal injuries for the book he is now just finishing. The list of mentors goes on and on. I forgot Nathan Englander. Jonathan Safran Foer. Colum McCann too, although he has since come to join the faculty.

Of all the things I do at Hunter, this seems to me almost the most important, to close that huge, lonely gap between the kitchen table and the world of literature.

But when we’ve done all that, although the Hertog Fellows now know, say, how a great writer uses research, or what A.M. Homes’s apartment is like, they’re still those anonymous people you see on the 6 train, reading Bruno Schulz. You’ve seen my students. You’ve thought, Is this a teacher, a barman with a taste for literature? One day you’ll be reading their book, maybe, but for now, as the train does that violent chiropractic jerk between Grand Central and 33rd, the only thing that is clear is that these young writers are unstoppable. No one reads fiction anymore? Says who? We are living in the middle of a roar of literature. The national newspapers are performing the surgical removal of their book-review pages like slick lobotomies, but the fiction writers continue like so many thousands of song-and-dance Rasputins who refuse to die. They’ll be there when we wake from this dark time and realize what all those “true stories” have really been. Imagination Dead Imagine.