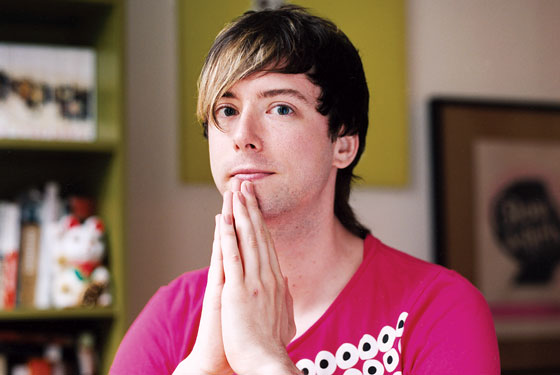

JOSHUA WILLIAMS

21, from Andover, Massachusetts

Williams, a Princeton senior (and Harry Potter junkie), made his first trip to Africa in 2005, when he worked to advance AIDS education through Swahili street theater. Returning to Kenya in 2006, he did research for his creative-writing thesis, whose protagonist is a pharmacist because, says Williams, it felt “like maybe a more liminal figure than a doctor would be.” An excerpt from that work is below.

In His Teacher’s Words

“From the first, I recognized Josh as a fellow writer,” says Joyce Carol Oates. “And while I oversaw his work closely, I had few opportunities to ‘correct’ him in any way.”

From “The Window House”

Turner drifts in and out of a doze. He didn’t sleep much on either the Newark-London or the London-Nairobi flight—and that in intermittent, shallow unconsciousnesses—and now his body is straining for release. He thinks of his pills, in the zippered inner pocket of his shoulder bag—but it’s down under his feet and now the children are draped heavy across his knees, so there’s nothing for it. So he sits and waits and watches, drifting in and out of dreams: the long silver fuselage of the bus, oncoming headlights like star-points, like bright low stars—the scattering of lights in the fields—Bird’s looking-glass eyes—mother, Africa—the rattle and stomp of potholes, dancing, sex, down oh down—that pervert baby soon—what do you care what do you care—hot sick balloon reach of doubt, change, little towns flash—reaching—oh please oh reach—

Dawn wakes him. He rubs his eyes, shifts against the ache that’s gathered in his neck and the knobs of his joints. They are edging along a narrow, sandy road riddled with potholes and lined with ramshackle chop shops, fruit vendors, barbers and bars. Here and there: handfuls of tall, ungainly palms. Mottled yellow light falls through.The road doubles back on itself now, to skirt a little hill, and Turner sees they are midway back in a line of mud-caked trucks trundling across a causeway bridge. Off to the right—down over the lip of the bluff, dotted mangroves, the sudden turquoise sea—there’s what looks to him like a shipyard or a small oil refinery. A nest of bones built black against the rising sky. And then Mombasa Island itself, straight in front of him down the tunnel of the bus: trees and coral rock and low, sad, building-block buildings, the spindly green and grime-white minaret of an unseen mosque, the rabble of traffic. For some reason he feels he should be surprised that this is what it is—but then he doesn’t know why, since he doesn’t know what he expected or even if he had expectations at all.By the time they arrive at the depot—a waiting square, an office, berths and berths of sleeping buses—it is all-the-way morning. Shopkeepers are out sweeping their patches of sidewalk with hand-brooms like wooden whisks. Men in red and blue aprons dot corners, hawking newspapers. Taxi drivers and family men jockey round the bus as soon as it stops, reaching up to tap on the windows with pink circle fingertips, calling out names. At this, the others in the bus wake, stir. The women on either side of Turner start and smile and shake their heads and lift their still sleep-heavy, limp-limbed children off his lap. He imagines grim, silent Emmanuels out there waiting for them, taking them in their swift, lean arms.The taxi driver that spots Turner first as he descends from the bus claims him as his own, leads him by the wrist over to his car and tells him wait with little flutters of his hands. Turner leans back against the car in the sea-heat, watches the driver dodge through the crowd. His mind wavers—the exhaustion, maybe. Everything around him seems strange and bright and weightless. Where are you going where have you been.The driver returns after a minute or two, bumping Turner’s suitcase out behind. “Go go go go,” he says, and prods Turner into the car. “We go where?” Turner shows him Dr. Al’s dogged and wrinkled index card.“Okay okay okay,” he says.They drive slowly through the clogged and bleating streets. Now it’s practically rush hour, and vans in garish racing colors (with slogans like THE TERMINATOR or 50 CENTS air-brush stenciled across the back) stop and go and spit out clots of men and women. Blue suits and ties and flowered blouses and long white robes and saris and tourist tan and backpacks, black purdah with only eyes showing, move like a current. Turner’s driver threads his way through, looping back around into what Turner guesses is Old Town, the Muslim Quarter: older houses with carved wooden doors, the rattle of paving stones, souvenir stands.They come to a stop at the far end of a quiet, cobbled square with a red Coke-a-Cola umbrella listing against the cistern and the smell of the sea. The driver gets out and points Turner around the corner to a shabby, anonymous shop with a lettered sign that says Curios in script. There is a toy cannon on the ground by the open door. Turner pays the driver, who smiles and flashes him the peace sign and disappears.The inside of the shop is warm and dark and mothball. It takes Turner a minute for his eyes to adjust. The flat black rounds into indistinct gray outlines, then colors, then stacks of books, a dining room chair, tribal masks and carvings, an enormous metal elephant, two gramophones, standing bolts of indigo cloth, boxing gloves, bicycles, Indian gods, records, oars, seashells, shoes. “Hello?” Turner says, struck.“Karibu ndani.” Turner starts. An old man sitting in a chair off to one side is watching him. His enormous glasses fishbowl his eyes. Leather sandals, ankle-long white robe, salted black goatee, Arab skin, round embroidered yellow hat.

MAAZA MENGISTE

36, from Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Mengiste left Ethiopia at 4, during the communist revolution—a period that’s become the backdrop to her novel-in-progress, excerpted here. As a child, she lived with a host family. And before attending NYU’s graduate program, she says, “I had never written anything about Ethiopia at all. That blank page is scary.” Now represented by an agent, she finds it no less daunting. “I can’t write in public anymore, because I still get emotional.”

In Her Teacher’s Words

“She has a poetic sensibility in the best sense,” says Irini Spanidou. “You feel the immediacy of her thought.”

From Untitled Novel

The human heart, Hailu knew, can stop for many reasons. It is a fragile, hollow muscle the size of a fist, shaped like a cone, divided into four chambers that are separated by a wall. Each chamber has a valve, each valve has a set of flaps as delicate and frail as wings. They open and close, open and close, steady and organized, fluttering against currents of blood. The heart is merely a hand that has closed around empty space, contracting and expanding. What keeps a heart going is the constant, unending act of being pushed, and the relentless, anticipated response of pushing back. Pressure is the life force. Hailu understood that a change in the heart can stall a beat, it can flood arteries with too much blood and violently throw its owner into pain. A sudden jerk can shift and topple one beat onto another. The heart can attack, it can pound relentlessly on the walls of the sternum, swell and squeeze roughly against lungs until it cripples its owner. He was aware of the power and frailty of this thing he felt thumping now against his chest, loud and fast in his empty living room. A beat, the first push and nudge of pressure in a heart, he knew, was generated by an electrical impulse in a small bundle of cells tucked into one side of the organ. But the pace of the syncopated beats is affected by feeling, and no one, least of all he, could comprehend the impulsive, sudden, lingering control that emotions played on the heart. He had once seen a young patient die from what his mother insisted was a crumbling heart that had finally collapsed on itself. A missing beat can fell a man. A healthy heart can be stilled by nearly anything: hope, anguish, fear, love. A woman’s heart is smaller, even more fragile, than a man’s.It wouldn’t be so surprising then, that the girl had died. Hailu would simply point to her heart. It’d be enough to explain everything.

He’d been alone in the room, the soldiers smoking under a large streetlamp outside. He could see their long shadows lengthening over the bare and brittle lawn as the sun swung low, then lower, then finally sank under the weight of night. It was easy to imagine that the dark blanket behind him had also swept into the hospital room, even though the lights were on. It was the stillness, the absolute absence of movement, which convinced him they, too, this girl and he, were just an extension of the heaviness that lay beyond the window. She’d been getting progressively better, had begun to wake for hours at a time and gaze, terrified, at the two soldiers sitting across from her. The soldiers had watched her recovery with relief, then confusion, and eventually, guilt. Hailu could see their shame sitting on their shoulders, keeping them hunched over monotonous card games and continually leaving for smoking breaks.It hadn’t been so difficult to get the cyanide. He’d simply walked into the supply office behind the pharmacy counter, waved at the bored pharmacist and pulled the cyanide from a drawer that housed a dwindling supply of penicillin. Back in the room, Hailu prayed over the girl and crossed her. Then he opened her mouth and slipped the tiny capsule between her teeth. What happened next happened without the intrusion of words, without the clash of meaning and language. The girl flexed her jaw and tugged at his hand so he was forced to meet her stare. Terror had made a home in this girl and this moment was no exception. She shivered though the night was warm and the room, hotter. Then she pushed her jaw shut and Hailu heard the crisp snap of the capsule and the girl’s muffled groan. The smell of almonds, sticky and sweet, rose from her mouth. She gasped for air, but Hailu knew she was already suffocating from the poison; she was choking from lack of oxygen. She took his hand and moved it to her heart and pressed it down. He wanted to think that last look before she closed her eyes was gratitude.

It was only his nurse, Almaz, who’d recognized the vivid flush of the girl’s face, the hint of bitter almonds, and known what had happened. She’d walked in just as Hailu was explaining to the soldiers how electric shocks had damaged her heart. “Oh,” Almaz said. “Yes,” she collected herself. “It was too much for her.”The soldiers had been agitated. “We reported she’d be back in a few days. People are expecting her,” one said. “I’ll explain it all in the death certificate,” Hailu reassured them.But Hailu had been summoned to jail, only one day after filing the report. His presence was requested in writing, delivered to his office by a skinny soldier with firm steps.“Arrive by dawn,” the soldier said. “The Colonel starts early.”“What’s this about?” Hailu looked at the inked signature at the bottom of the letter and tried to imagine the type of man whose hand moved across the page with such jagged sweeps of the pen.The soldier stared at him and Hailu felt a shiver crawl up his spine. His light brown eyes were crisscrossed with red veins. “It’s just to talk.” Hailu tried not to think about the fact that no one ever returned from a summons to jail. “Should I pack a suitcase?” Most prisoners were ordered to bring a suitcase under pretext that they’d be released. “It’s unnecessary,” the soldier said. “Tomorrow,” he added before leaving.Now, Hailu stared into the dark in his living room, his back straight as a tree, and waited, though for what, he wasn’t sure.

MARK EDMUND DOTEN

28, from Cottage Grove, Minnesota

Doten is a product of the blogosphere. He fed his interest in politics as an associate editor at The Huffington Post and his passion for fiction by submitting work to novelist Dennis Cooper. Now he will be included in Cooper’s collection Userlands: New Fiction Writers From the Blogging Underground and is working on a novel with a premise just odd enough to fly. Green Zone Kidz will consist of linked short stories in the voices of Bush officials, vets, and, in the case of the excerpt below, Osama bin Laden in his cave.

In His Teacher’s Words

Two novelists at Columbia have taught Doten—Sam Lipsyte and the chair of the M.F.A. program, Ben Marcus. “We haven’t seen anyone like him,” says Marcus. “His stories are crazed monologues that grow progressively menacing as you read them. They’re political in a kind of way that’s very hard to pin down.”

From “Waziristan”

They found the Jewboy picking his way through the boulders near the cave system. He smashed a lizard with a rock, scuttled up to the next boulder and smashed another lizard. The Jewboy smiled vaguely, head lolling, as he pounded out a third lizard’s guts, my lieutenants tell me.“The heat! Who smiles in such heat?” they ask. Through the long afternoon the sun blasts our mountain, the fiery air jams itself into the furthest recesses of the cave system, or as deep as we’ve yet managed to venture. There may be deeper passages, cooler passages. For this I have no evidence, only suspicions and the occasional chill.“We thought of killing him,” the first lieutenant says, throwing the smiling Jew to the floor.“But we brought him to you instead,” says the second lieutenant.The third and the fourth lieutenant, cleaning their rifles in the corner, turn and nod. “Yes. Yes. Zionist pig.”The pig smiles. I raise him up by the hair and gaze into his liquid eyes. No reflection there, just black oil.I tell them that whenever you look at a Jew, you are in fact looking at a smiling Jew. The Jews are obscene clowns, I say. And drop him.

A dozen lamps spill light and shadow across the floor, after the boys tend to my blood each morning they tend to the lamps, topping up the oil. I don’t think it’s mere fancy to say that for my birds this is the most pleasurable time of day. A dozen cages hang at the perimeter of the chamber, the red-footed falcon, the purple gallinule, corncrakes and bullion crakes, as well as an Indian nightjar, a quantity of jack snipe and the oldest birds, a pair of ring-necked parrots with their incompetent, bovine faces. When the lamps are refilled a warmer light spills through the chamber and my birds lift their heads to call to one another, black eyes flashing, as though the darkness had been banished through their own agency. All but the snipe, who flap away from the light, batting demented at the slender sycamore bars, crying for a night they think they’ve lostOf course, there’s no night in our cave system, properly speaking, only heat and chills. The lieutenants and boys venture outside, and thus they remain in touch with—let us even say trapped by—the illusion of day and night. In fact there’s no such thing, no day, no night, only a rotation of bodies, only a machine to clean the blood and swarms of beetles where once there were none, even a child knows this, but to learn a life without night and day, without the idea of night—to internalize such a way of living—is a very different question, and one that has gripped me for years. It comes to me as I study the pig that the Zionists have always in all their dealings kept an eye to the not-night, and our little Jewboy, whose head is now rolling in my direction, this Jew turning from the wall to face me, watches not only, or even primarily, me. He holds an eye to the not-night.But here perhaps I go too far. It seems unlikely that The Jew at large is privileged to understand this—every day, every dusk, every night, all of it not-night—and certainly not this mute and smiling fool. Nevertheless: how to explain the persistent survival of the Jewish Race, how to explain the Jewboy, still alive on the floor of the central chamber, knees to chest, hands rubbing his snake-oil eyes before vanishing again under the blanket?I mastered my disgust soon after his arrival. This was primarily, I believe, a disgust at such a face: the outsized eyes, the womanish, exotic features. God grants us disgust, praise his wisdom, so that we correctly learn the world for all its poisons. But He offers us as well the ability to master our disgust, in order that we might better rid ourselves of these poisons. And so, by the grace of God, it has become my mission to replace, or rather augment, my current understandings of The Jew—instinctive, scriptural and so forth—with something else, let us call it, for lack of a better term, a scientific and contemplative understanding. For instance, that first night I did not allow him a blanket. The next I relented. Call it an experiment, the basis of a parable: The Jewboy and the Blanket. I am interested, too, in his reaction to the central chamber. I hold in my head a complex understanding of the chamber: of my own love for it, of the aversion of the lieutenants, the fealty of the boys tending the generator and the elevator, boys periodically pausing to stare in wonder overhead. The Jewboy’s reaction could well be the missing piece, the one that makes it all come clear. For instance: am I the only one who feels these drafts that shake you to the bone? Every hour or two I’m struck with chills, but I can’t ask them, I won’t. Last night, however, I saw the Jewboy assiduously tucking the blanket under himself, tucking it under for hours. I would like to quiz him on his feeling about the chamber, on this tucking-under, to find out how he sees this place, how his vision differs from the objective reality: a chamber roughly square, each side close to 40 feet, the floor nearly flat, as though made by man, or by God for man. On the east wall, an elevator, a boy keeping watch over the elevator. Opposite this, the chamber’s mouth, opening onto what you might call the cave system’s ante-chamber, which snakes off in a dozen different directions, to deadfalls and blank stops, new caverns and even a pair of phosphorescent vaults that only the youngest of the boys can reach, crawling on knees and elbows through slender worming tunnels. Against the south wall of the central chamber—the broadest by several yards—I sit on my pillows, staring across to north side of the room, the Zionist there, a 3 foot chain running from the cave wall to that bare slender ankle. The roof of the chamber towers high above, lost in darkness, and when the Jewboy turns over the chain’s rattle echoes down on our heads like money.

MARTIN HYATT

36, from Covington, Louisiana

Hyatt spent his childhood surrounded by storytellers. His aunts told of seeing Jesus, and his Pentecostal preacher spoke in tongues, while he found himself lost in the lyrics of Merle Haggard. A 2004 graduate of the New School’s creative-writing program, he’s now crafting a new form of southern lyricism with gay characters and plotlines.

In His Teacher’s Words

“He’s a poet in the style of Carson McCullers,” says the New School’s Jackson Taylor. “It’s musical. You know how dogs hear a whistle and their ears perk up? The sound is so good.”

From His Novel, “Grit, My Love”

They say towns like this don’t exist anymore, but I know that they do because I live here. Noxington is one of those towns where the big stores that sell everything and stay open all night have yet to be built. And it doesn’t have those places where people sit at tiny computers drinking complicated coffees and eating strange muffins. It doesn’t have those restaurants where everyone dresses like they spend a lot of money on clothes. There are places like that in towns thirty, forty or fifty miles away, in Mandeville and Slidell and, of course, New Orleans. But here we don’t have that stuff, and sometimes when I can’t sleep or when I’m bored I want those things, that coffee, those computers, those clothes. But I stay here. I stay because Granddad needs me and because in the past when I’ve tried to leave I get sick. I get dizzy, and it’s like I’m going to throw up, pass out or die or something. I am not a good traveler. But one of these days, I’ll leave. I’ll relocate to a place where there are more people and more things. But for now I stay. Those of us in towns like this stay put. Besides it’s the only thing I know how to do well. I am excellent at staying.But now I am turning thirty in this town where nothing ever happens. It can be said that the fire twenty-five years ago was really something, certainly the biggest event in my life. But if you push something like the fire far enough back, it becomes less your personal history and simply general history. Something you can refer to the way you refer to a history book. People still talk about the fire much more than me, so it is like it is their event, something they have to carry around instead of me.I am spending the morning of this birthday sitting in the window of the diner where I work. Birthdays are the sort of thing I like to keep a secret. And not only because I am getting old, but because I don’t want anyone to feel sorry for me or to be sad about what I have not become. They blame what I have not achieved much more on the fire than I do. On this thirtieth birthday, I don’t want to think about my classmates whose photographs I always see in the morning papers; heading civic organizations, running for public office. They are doctors now, lawyers. And it seems as if they are all married. I see them smiling with one another in those black and white newspaper photographs. When viewed at just the right time on the right day, the normalcy of marriage seems right. It makes sense to be them.There are no customers in the place. People get a late start on Sunday mornings. Not even my granddad, the owner, is around. He always goes fishing on Sundays. Jose, the cook, and G., the dishwasher, are out back smoking a number, so I take control of the jukebox and put on some George Strait …I look around the diner, which caters mostly to construction and road crew workers, hopped-up truck drivers, and to people who work at the courthouse about three miles up the road. And occasionally, to people on the highway looking for a place to get a quick bite to eat as they travel to exotic places where it snows or places that smell green. This world, my world, is muggy, smells like grease and ketchup. It is a world of run down-jukeboxes and shaky folding tables where people grow old in a most expected way.When your parents are dead, I guess you don’t worry so much about becoming them. Instead, you spend your life wondering who it is you are supposed to be. In a town like Noxington, becoming yourself is never an option.“Hey Boz, you want some of this?” G. yells from out back.“No. Go ahead,” I say, knowing that smoking pot will just make me more bored. G. and Jose smoke to make washing dishes and frying eggs less dull. By smoking, they turn the diner into a dream. But I have the natural ability to do this, to see everything as a dream. I also know from that fiery night I spent in the truck that you always wake up from dreams.I can see them in the kitchen, wrestling with each other like two overgrown kids. They fight with affection, like two lovers in a movie, tussling before a kiss. Sometimes they call each other names, but I know they love each other because I often see them in the kitchen, looking around curiously, making sure the other one is still there.

ELLIOTT HOLT

33, from Washington, D.C.

Holt’s mother told her that she began telling stories as a toddler. By 7, she was already dreaming of the writing life in New York—the practical version, where she wrote ad copy for a living and fiction in her spare time (which is exactly what happened). Holt, who’s lived in Moscow, London, and Amsterdam, is writing a novel that draws on the expat life, but the story excerpted here was inspired by a more private experience—the death of her mother from cancer.

In Her Teacher’s Words

Holt’s “prose crackles,” says Michael Cunningham, who runs the fiction section of Brooklyn College’s M.F.A. writing program, which she is graduating from this spring. “She understands that, in fiction, the sounds of words matter as much as their meanings.”

From “Evacuation Instructions”

They are getting ready to spend a weekend in the country, in the wilds of Connecticut. There will be swimming and she’s trying to find a particular bathing suit.“That brown one, she says, that makes me feel like I’m in St. Bart’s.” She is bending over, probing corners of her closet that she rarely enters. “What time are they expecting us?” she says.“Lunchtime,” he says. “They’re having a big lunch in the garden. Sheila’s usual approximation of Tuscany.”He is looking at their picture in Vogue. In the photograph he is in profile, looking at her. The light has caught his bald spot.“My God,” he says. “I’m old.”“You’re not old,” she says from the closet. “You look very dashing.”“I’m forty-four,” he says.“Ah-ha!” She stands triumphantly, holding the Lycra suit aloft like an Olympic medal. “I’ll drive,” he says.His wife usually likes to be behind the wheel. But today she takes the passenger seat without complaint. She fastens her seatbelt. It’s a perfect July day. Cloudless, the sky is an empty promise.When they pull into the driveway of the house, they can hear the dogs barking. Every time they see Sheila, she seems to have more dogs. He carries the bags inside—he likes these opportunities for chivalry—and his wife follows. He pushes open the screen door and then four dogs—two black ones, poised and alert; one fat and golden, with drool slipping out of its mouth; the last small and quivering and a mottled white—come bounding down a long hallway, pushing worn rugs out of place in their enthusiasm. There are few things more comforting than other people’s chaos.They spend the night in the guest room. And as they fall asleep with one of Sheila’s black dogs sandwiched between them his wife takes his hand, and sighs. It’s a long, wistful exhalation. It’s a sigh that causes the dog to shift position, so that there are suddenly canine toenails pressing into his stomach. “Sweets?” he says, but she is already asleep.He awakes to the sound of the dog licking. The dog gulps when he swallows; his licking is greedy and vaguely sexual. He opens his eyes and sees that the dog is licking his wife’s face. Licking up the blood as if he was hired to do it.He shakes her, watches her sit up, sees the blood roll down her chin, faster now, and the dog sits up, leans closer to her, tilts his head, extends his slimy pink tongue. The dog is scruffy, of a breed he can’t identify. It has no business here. His wife looks at it, for a moment, as if pleading for mercy.He breaks the speed limit on the way back to the city, heads straight to the hospital and then lets her off before he goes to park. Alone in the garage, he wends his way through the dark rows of cars, and suddenly feels like he can’t breathe. If he has a heart attack, here in this forsaken place, would they find him? Would an ER nurse wander out here for a smoke break and perform mouth-to-mouth resuscitation on his crumpled body? He finds his breath again, shallow and heaving at first, but then he’s moving into the light outside the garage and crossing the concrete toward the hospital entrance. You just have to make it inside, he thinks. Then you’re in good hands.

“How can it be malignant?” she says.He can’t believe it either. His wife’s body is rife with tumors. The oncologists say she will be lucky to live six months. The first tumor was in her nasal passages but there have been many tumors discovered since. The doctors announce their detection as if shopping for fruit. This one the size of a grapefruit, this one a plum. He devotes hours of every day to research. He trolls the Internet for information about clinical trials for which she might be eligible. Their options are limited; she’s already Stage IV and most trials are only open to patients in whom the disease has not advanced so far. Applying to clinical trials is like trying to get into college. They discover a meritocracy based on immune systems, in which certain patients are valued for the unique way in which their bodies respond to the challenge. His wife’s doctors present case studies of patients for whom various treatments worked, and it brings out his wife’s competitive streak.“I can handle this one,” she says to her oncologist one day.They are trying to persuade him to recommend her to the team running a particularly compelling clinical trial. “I don’t know,” the doctor says, sucking in air to punctuate his doubt.“I want to try it,” she says, as if they are talking about scuba diving or hang gliding, instead of a toxic cocktail that will be administered into the bloodstream via IV.They have read the literature; the treatment has been effective in a mere five percent of patients. But his wife is used to being a success story.“We’ll see,” says the doctor. “We’ll see.”He imagines making his case to the doctor leading the trial. Exhibit A: the X-ray with the original tumor. Exhibit B: a CAT scan that reports metastases as if they are geological formations. He’d put his wife on the stand to display her incredible endurance. He reads turgid medical journals, clipping any articles he finds relevant. There are drugs that sound like the stuff of science fiction: Interleukin II, Gemzar. There are various immuno-therapies described in militaristic prose. Targeted attacks on rebel cells. It reminds him of his wife’s reports from Kinshasa. He dedicates a file box to the case and labels folders for insurance claims, prescription information, records of radiation sessions. When she is finally admitted to the trial, he considers it his victory.

DAVID ROGERS

33, from Peekskill, New York

Growing up, Rogers spent a few years in special-ed classes. “I don’t think they knew what to make of me,” he says, “until I started writing stories and they could see that I had a brain, possibly an imagination.” Now an editor at Picador, he’s writing a novel about researchers studying an invented hoofed animal, and he knows he’ll find an agent in his own good time. “To me, the pace at which a writer is created is glacial. I knew that right off the bat, and I was okay with that.” The excerpt below is from one of his short stories.

In His Teacher’s Words

“David can build his own parachute, construct the weirdest emotional landscapes, go beyond what he has any right to know,” says Peter Carey, director of Hunter College’s M.F.A. creative-writing program, which Rogers attended part-time from 2002 to 2006.

From “The Tie-Down”

You have to work fast on the phone. Say hello, tell them where you’re calling from, then go right into it. You‘ve got about ten seconds to hook them. If in those ten seconds my bullshit isn’t working, naturally the customer hangs up. Many of them did this before I could say a word, two words, or they had silently done it while I was talking and I didn’t hear them. There are things you’re supposed to say to keep them on the phone, tie-downs. Just as you’re about to hang up, just as you think your mind is made-up, you’re pulling the phone away from your ear, and then you hear my voice through the phone say something presumptuous, a little provocative, a little personal, a few words that get the phone back up to your sweaty ear. Sometimes I’d throw out a bogus crime statistic, sometimes I would say there was a free trial period. You want to know what was my favorite tie-down?“But sir, isn’t the safety of your family important to you?”That one made me uncomfortable at first, it just seemed like such a judgmental thing to say, like I was making the customer feel bad. And that’s why it worked every single time. I expected someone to say “How dare you, how dare you, say that I don’t care about my family?” Never happened. Not once. They always said things like “of course, of course, and I think my house is pretty secure, why would I need … ” and the longer they talked to me, the more they found things to worry about in the world.I’m not in the home security business anymore. It’s strange to think that I talked all of these people into buying this thing, really made them think it was worth their money, but could never convince myself of the same. Personally, I don’t think any of those tie-downs would have worked on me. I would have hung up on myself. I should have gone to work for Medico. Thwick!I was eating in a crowded deli in the Flatiron District the other day, when a man a little older than myself asked if he could sit at my table. There was no place else for him to sit down, so I gestured at the chair with my head. The guy was a couple inches taller than me, his face was tanned, like he just got back from Florida or something. I imagined that this guy must be an actor, maybe even a famous actor, because his face had those large features that make you think of people in show business. The man carefully unwound the tan herringbone scarf from around his neck and pulled off his trench coat, draping them over the back of the chair. He wore a gray wool sport coat and pressed white shirt. The tanned skin of his neck was radiant against the open collar. Before he sat down, I caught another look at the scarf, and thought I’d ask him where he got it after I’d finished half my sandwich.The man sat down and played with the toothpicks in his turkey club for a minute, and although I didn’t look up at him, I’m pretty sure he was staring at me, waiting to catch my attention.“You look like a theatre-lover,” he said, his voice a rich baritone.“Not in years,” I replied, trying to think of the last play I had seen. It was something called “Waiting for Lefty.” Crummy.“Well, my name is Roderick Lansing, and I have written and produced an epic play at the Stella Adler Theatre. It is a large scale staging of the stand-off between the Jewish Zealots and the Romans at Masada, an exciting piece of theatre that has been playing to sold out houses since the beginning of its run.”“Good for you,” I said.“A block of tickets has just been made available to me, and I would very much like for you to see my play.”“So you’re giving away some tickets?”“Who would you bring with you to see it?”“I don’t know. My wife, I supposed. Maybe I would double date with my buddy.”“So, four total? In that case, I can release these tickets to you for only five dollars apiece.” “I thought you were giving them away.”“An evening of epic theatre for only five dollars, I don‘t think you‘ll find a better deal than that.”“No thank you,” I said. I always feel awkward saying no to a salesman. The man sighed and settled into his chair. I did not look up at him, but could sense the forlorn breathing of failure across the table. Then I looked at his hands, and he carefully removed the toothpick from one half of his turkey club. He held down the piece of whole wheat toast with his finger, waiting to eat. “Never thought, at my age, I’d still be still be a street fighter,” he said.Most of the salesmen I know don‘t like to talk about the rejection. We convince ourselves, both customer and salesman a like, that losing the sale is nothing personal. For every thirty hang-ups or no-thank-yous, I got someone to buy an alarm system. That ratio of rejection is a bit staggering, and I’ll admit that the hang-ups got to me; sometimes it rolled off and I didn‘t care, but other times, if a pitch suddenly went sour half-way through, or if a customer just got prickly and rude, then it really hurt. I‘ll admit that it hurt. “Tell me the first scene,” I said. “If I like it, I’ll come see the rest.”