It must be the mosquitoes!”

All day long, the baronessa has been racking her mind, trying to figure out what went wrong. As she wanders the sprawling grounds of Santa Maddalena, her writers’ retreat in Tuscany—past the rosebushes and the cook’s quarters—she keeps asking herself the same question: What caused young Benjamin to cut his stay short? Benjamin is Benjamin Kunkel, author of the novel Indecision, which the baronessa was informed was the book last season in New York. Some fawned, others were predictably vitriolic—which made Kunkel just the sort of writer the baronessa courts to her compound: happening, benignly controversial, established. Calls were made, a note written, and three weeks ago he arrived, toting an entire suitcase of Beckett and Sam Shepard, set on finishing his first play. “It’s about … flies,” was all he would say, precisely the kind of deliciously cryptic, writerly comment the baronessa relishes.

But now he is leaving—for London. Something involving his father, family friends, a birthday; the baronessa was unconcerned with the details. What was important was that Benjamin was breaking the code that defines the artist-patron relationship: The artist is to be charming until excused. And in the case of Baronessa Beatrice Monti della Corte von Rezzori—an impatient, charismatic, preternaturally controlling woman—this leave-taking is also intensely personal. Santa Maddalena is her home, converted into a retreat after the death of her husband, the novelist Gregor von Rezzori, in 1998, and the baronessa, a widow with no children of her own, imagines herself both mother and muse to her “fellows.” Michael Cunningham understood this, as did Zadie Smith. Like Kunkel, they were given the compound’s choicest work space, in the Tower: four stories high, with a view of the valley and a Miró above the antique wooden desk. They came, they flourished, they saw through the long string of intimate, on-the-clock lunches and dinners, regaling Beatrice with their wit. They wrote lovely thank-you notes and referenced the baronessa in their acknowledgments. They asked to be invited back. They most certainly did not make an abrupt exit.

What makes Kunkel’s premature departure particularly troubling is the fact that, at 80, the baronessa is determined to spin her creative Utopia into her legacy, a gift to literature not to be taken lightly. She’s wealthy, but she’s not rich; Santa Maddalena has no endowment, and though a university might swoop in, its future is uncertain. And so the idea that one of her progeny might be perfectly happy to get on with other matters in his life has her piqued. There must be some face-saving way to account for his change of plans. Yes—in a Kafkaesque turn, actual bugs have gotten in the way of Kunkel’s metaphoric ones. “Benjamin comes with one red dot, and he says, ‘What is it?’ And I say, ‘I don’t know—the bite of a mosquito!’ He is charming. I like him. Very intelligent. But for a young man like that, he has”—a bemused shake of the head—“a mania.”

In the world of publishing, Beatrice (pronounced in the Italian manner) stands out as one of the last true eccentrics, a relic of a pre–Da Vinci Code age in which personalities rather than focus groups shaped literature. Her selection process is loose and informal, played out over numerous lunches and social events when she comes to New York to stay at her Upper East Side apartment. While in town she consults with a cadre of advisers that includes Jonathan Galassi (editor of Farrar, Straus & Giroux) and Bob Silvers (editor of The New York Review of Books), who offer tips as to who should be among those fortunate enough to be invited to Tuscany. “It is very strange,” says Andrew Sean Greer, author of The Confessions of Max Tivoli. “Jonathan Galassi said, ‘You’re going to get a call from this woman Beatrice. She’s a baronessa, and you should go.’ ” This year her plan is to arrive in New York a few weeks before Christmas and check in with some of her publishing friends—agent Andrew Wylie, Joan Didion’s editor Shelley Wanger, and “Sonny and Graydon.” And soon the next round of writers will receive their nods.

Apart from Kunkel, the latest group includes the Spanish novelist Marcos Giralt Torrente, whose books have been translated into six languages (none of them English), and the British writer Marina Lewycka, whose debut, A Short History of Tractors in Ukrainian, was up for a Booker. As the bell rings for lunch, all three descend from their respective studios and join the baronessa and her pug, Alice, on the poolside patio. Hostess to a breed not exactly known for their extroversion, Beatrice is fond of turning meals with writers into impromptu seminars on etiquette. “Vendela Vida told me she learned seven new things here each day,” she says of the novelist and editor of The Believer. “When she arrived, she was cutting her spaghetti with a knife!” And of Gary Shteyngart, author of Absurdistan, she explains, “He learned to take a bath here.” (Of his Tuscan transformation, Shteyngart was inspired to write in the guest book, “I came barely knowing the difference between a horse and a cow. I leave a coffee-making, salad-serving Man of Nature.”) And now, as dessert is served, Beatrice turns to Kunkel, who, it appears, is unversed in the consumption of fresh ricotta. “You must use the brown sugar,” she instructs, waving a small silver spoon. “This is the way it is eaten.”

“Oh, thank you, Beatrice,” he says.

At Santa Maddalena, the provenance of most objects is bound up in Beatrice’s own history: a wooden objet from a safari in Africa, works by Fontana, Tàpies, and Hockney from the days when she ran a gallery in Milan. And the predominant aesthetic is what the baronessa calls “Oriental,” the inspiration for which is revealed during a tour of her private rooms upstairs. She points out a small black-and-white photograph of a striking young woman with dark curls, a portrait of her Istanbul-born Armenian mother, who fled the massacre to live in Rome. There she married an Italian aristocrat and gave birth to a daughter—only to die of typhus at 25. As Bruce Chatwin once wrote, it was her mother who “gave Beatrice an idea to which she has clung all her life: that glamour—real glamour, not the fake Western substitute—is a product of the Ottoman world.”

Trailed by the ever-present Alice, whose collar of silver beads spells BOW WOW, Beatrice heads into the bedroom, modest quarters if you happen to miss the drawings by Claes Oldenburg and Giacometti. More opulent is the bathroom, with two tubs sunken into the floor side by side, arranged to face each other—her husband’s idea. “Well, it’s a bit sad now,” she says, looking down at the porcelain couple, “as the other tub is never used.”

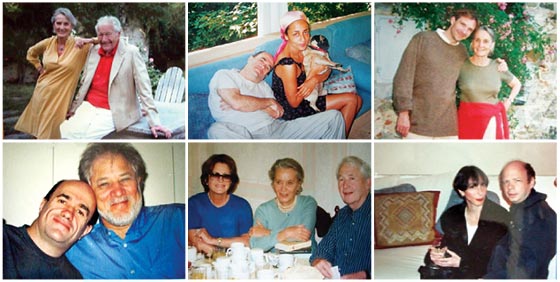

The baronessa’s photo albums give the impression of two very well-matched partners. There is the picture of the nearly naked pair in bed together, snapped by Beatrice in a mirrored ceiling. And there is Von Rezzori in a fine suit and ascot, downing oysters at a bar in Vienna. The caption in French reads, “Souvenir of the time my wife was in the hospital.” “We were traveling, and I hurt my leg and needed surgery,” Beatrice explains. “He left me and continued on to Austria—ha!” The writer Deborah Eisenberg, who knew the couple well, says, “I think when people think ‘the baronessa,’ they’re imagining somebody who’s saying, ‘Oh, I’m sick of peacock’s eggs, take them away!’ But she’s the least jaded person I’ve ever met.”

Of George Plimpton, she declares, “I did not like his social manner.” But then there’s Ralph Fiennes.

“I find my life very boring,” Beatrice likes to say. After her mother’s death, when she was 6, she moved to the north of Italy to live with her grandfather, a French governess, and several dogs, her existence that of a prewar Eloise left to wander the 30-room family mansion. Later, when her father was remarried to a “not nice woman” in Capri, Beatrice found her way into a circle of artistes, becoming the preteen pet of Max Ernst, Alberto Moravia, and Curzio Malaparte. “When people ask me how I know so many people,” she explains, “I say it’s because of Capri. I was the pretty girl of Capri, and I met all these writers, artists, homosexuals—and they would take me around, much like the pug.”

At 25, after World War II dealt a financial blow to her family, Beatrice founded one of the first European galleries to show new American art, Galleria dell’Ariete, where she exhibited works by Cy Twombly and “that beautiful, brilliant couple,” Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns. (“That was a time when there were no women in the field, and she and I were up against the boys like Leo Castelli,” says New York gallerist Paula Cooper.) When she met Von Rezzori, she’d already become an anomaly: a successful Italian woman in her late thirties, insistently single. Von Rezzori, or Grisha as he was known, was a writer nearly twenty years her senior, and with cinematic good looks that had led to bit parts in Louis Malle movies. Alex Liberman threw them a wedding party with Marlene Dietrich and Salvador Dalí in attendance, and so began Beatrice’s final incarnation, as literary patron.

Over the course of three decades at the villa, Von Rezzori wrote many books (including the classic Memoirs of an Anti-Semite, about World War II and its aftermath), and their home attracted various writers, artists, and filmmakers, who occasionally stayed as long as two years. When Grisha was dying, Beatrice told him she planned to convert it into a writers’ residency. He was indifferent to the specifics, more concerned that his impatient, intensely energetic wife have a project to keep her active. “Do not become a lugubrious widow,” he insisted.

But it’s unlikely that Von Rezzori believed Santa Maddalena would have any significant impact on contemporary literature. The notion that, since art is romantic, the process of making art must also be romantic—this was Beatrice’s fantasy. In reality, nothing could be further from the truth: Writing is sedentary, repetitive, often boring, and can be done in such aesthetically imperfect locales as a studio apartment in Brooklyn. Von Rezzori understood this. In his memoir, Anecdotage, he wrote of a guest at Santa Maddalena, “Doesn’t he too get the feeling that the whole thing has been staged so as to create the illusion of a form of existence unconnected to any truth?”

Talk to enough writers about their experience at Santa Maddalena, and a handful will complain—off the record, of course, presumably hoping for another stay marked by ricotta and afternoon swims. One attractive young novelist never recovered from being compared with the baronessa’s pug, and one fellow suggested that some guests were too class-conscious to enjoy their stay. “They iron your underwear for you!” says Andrew Sean Greer, still astonished. “That’s hard to take. You have to kind of decide that it’s fantastic, and there were a lot of writers who found it to be too much.”

The baronessa is generous with her social network; she introduced Gary Shteyngart to his Italian publisher and is campaigning for Deborah Eisenberg to have a run in France. But there is also a certain, mostly forgivable vanity behind her various projects. She intends, for instance, to preserve Santa Maddalena for the ages by having a handful of her fellows, some of them Pulitzer Prize winners, compose odes to particular rooms on the grounds. Shteyngart recently completed a piece on the Tower’s bathroom.

After her first stay, Zadie Smith wrote to her hostess, “When I arrived in Italy, I was all washed up. I hadn’t written properly for a year … I really thought I was all done.” She left with the first 121 pages of her second novel, The Autograph Man, in which a character is inspired by Beatrice (“I’m the older actress, the eccentric one”), and soon bought a pug of her own. She’s now looking for a place in Rome, and plans to study Italian. Specimen Days, the final third of which Michael Cunningham wrote in Tuscany, features a sci-fi lizard woman inspired by a reptile that refused to leave the Tower, and Greer’s next novel features a pair of twins named after Beatrice and her dog. “For me, it’s an intense pleasure,” says the baronessa. “Because what else do I get out of it?”

At dinnertime, everyone gathers around the stone table on the piazza behind the main house for a meal of fried zucchini, risotto, and Beatrice’s fearless name-dropping. Against a shrill chorus of frogs and the strange sounds of mating deer, we hear of “Isabella,” meaning Rossellini, who “goes into Central Park at night to rescue the birds that have fallen out of the trees.” And how John Malkovich once came for New Year’s dinner, “and I’d set up the table quite nicely, with beautiful plates and candelabras, and he put down his baby and changed her right there!” Beatrice’s deadpan delivery can make it hard to tell when she’s being serious or merely trying to spark conversation that meets the standard of her ideal salon. Of Salman Rushdie, she declares, “He has done nothing of importance since Midnight’s Children”; George Plimpton, “I did not like his social manner”; and Juliette Binoche, “like a spoiled French actress, not friendly at all, and so we did not become friends.” On the other end of the spectrum are those like Michael Ondaatje. “Michael is absolutely adorable. He has eyes like water, not blue, more complex. He exudes charm from every part of him!” And then there is Ralph Fiennes, a repeat visitor and one of the few who, bearing a vague resemblance to Von Rezzori, can bring out Beatrice’s girlish side. “He is really very, very handsome,” she says. “We went upstairs to watch Teorema, which is a Pasolini film Ralph had not seen, and he was reclining on the couch just so, like the Scarlet Pimpernel, and he has these incredibly long blond eyelashes … ”

“She is driving me crazy!” the novelist Torrente exclaims after dinner, in a moment of clandestine frustration. “She asks you a question, and then she changes the subject!” But he misses the point entirely: The novelist is here as a companion to this final chapter in the baronessa’s life. Besides, has he played tennis with Pedro Almodóvar or seen Joe Pulitzer in a toga? The young man should listen—this may be his last chance to hear her stories.

By the end of the meal, once the sky has grown dark, Beatrice may have a second wind and lead her group, wine and cigarettes in hand, to watch the fireflies by the rosebushes, where she once coaxed Zadie Smith into an impromptu performance of “Stormy Weather.” But on this night, as is the case more and more these days, the baronessa is exhausted and must bow out of the evening’s big plan: night swimming. “I think that would be great fun,” she tells her writers, “but I must say goodnight. I do wish I were not so tired.”