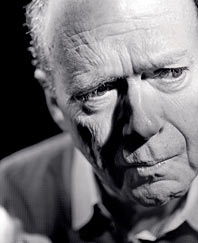

If Modigliani had painted Gerald Ford, the result might look a little like Frederick Seidel. The man is sumptuous. He hangs on the edge of a red-leather banquette behind his regular corner table at Cafe Luxembourg, cradling a second espresso, and his ash-colored suit—made to measure by Richard Anderson of 13 Savile Row—fits so perfectly that it looks like it was dusted onto his slender frame with a box of confectioners’ sugar. More excellent still is Seidel’s voice. When he says “past” it comes out “pahst.” His friend Diane Von Furstenberg had it right when she told me “Fred is a very luxury man.”

You might guess that Seidel, who’s 70 but looks younger, is a well-heeled psychoanalyst or maybe the CEO of a Belgian firm that manufactures missile cones. In fact, according to a great many influential people, he is among the two or three finest poets writing in English. He’s titled his new book Ooga-Booga, something any number of writers must have been dying to do for years, and it is both brilliant and deeply weird.

Don’t feel bad if you haven’t heard of Frederick Seidel. If each of his collections has become something of a beloved cult item, it is in part because he doesn’t participate in organized literary activity—Seidel doesn’t give readings, judge contests, teach, or, as far as I can tell, care to fraternize with other poets. Then there are the poems themselves. Preoccupied with politics, sex, and mortality—as well as the picturesque and expensive ways of staving it off—they haven’t always pleased reviewers. When the critic Richard Poirier put forward Seidel’s name while serving on a literary-prize committee, he remembers being surprised by the reactions of some of the members: “They found the poetry unpleasant, thought Fred sounded like a snob, and were put off by his descriptions of women.” The likely reason is that the poems are both ruthlessly honest—in the words of Seidel’s editor, Jonathan Galassi, “uncompromising to the point of cruelty”—and unflinching about the serious business of pleasure.

For one, there’s the sex. The new book contains a hymn to the tyranny of the penis, jauntily titled “Dick and Fred”; another, “Climbing Everest,” opens with a love scene involving a much younger woman—“It’s almost incest when it gets to this,” Seidel writes—and closes with the following observation: “A naked woman my age is just a total nightmare.” Then there’s the money, and there can be little doubt that Seidel takes immense pleasure in spending it. How else to make sense of the line “I am a boulevard of elegance in my well-known restaurants” from the poem “On Being Debonair”? Add to this Seidel’s close friends, who include Bernardo Bertolucci, Bob Kerrey, Jamaica Kincaid, Charlotte Rampling, Joseph Lelyveld, and David Salle. Many of them, particularly the women, populate Seidel’s poems in odd and intimate ways. A passage in “Nectar” revels in what reads like an unabashedly romantic interlude in Paris with Von Furstenberg: “At her old apartment at 12, Rue de Seine/We lived like hummingbirds on nectar and oxygen.”

Finally, there’s Ducati. Seidel not only writes poetry about the Italian motorcycles but owns four of them, and he will describe the bored-out, street-illegal, uncomfortable pro racers that reach 210 mph in minute detail. He rides them along out-of-the-way roads near his house in Sag Harbor and sometimes on Montauk Highway, occasionally hitting 150. His new ride, the six-figure 999FO5 factory Superbike racer, one of only eight made every year, was built for him in Bologna by hand. “When the mechanics found out they were assembling the bike for Seidel, the American poet,” he tells me, “they dubbed it Moto Poeta.” His voice purrs when he says this.

Still, the luxe, randy celebutante of the poems doesn’t jibe with the appealingly shy, gracious, and almost painfully discreet man who meets me. Invariably, those close to Seidel bring up his loyalty and generosity, particularly in the face of friends’ misfortunes. “When I was ill with cancer, Fred was the only person I spoke to every day,” says Von Furstenberg. “People have no idea how to read him,” argues Poirier. “Fred’s created a character named Frederick Seidel that has little to do with who he really is.” Seidel is having none of it. “Everything in the poems is true,” he insists. “You should take them at face value.” Problem is, Seidel dislikes talking about the poems, which he believes should stand on their own, almost as much as he does about his life. “What you’re struggling with,” he finally offers, “is that the man in the poems is the real man, while the man behind the poems just wants his privacy.”

Born in St. Louis to a Jewish family—his father owned a West Virginia mine as part of a coal-and-coke business—Seidel showed up at Harvard fully formed. “Fred was ahead of us all,” says his college roommate Charles Sifton, now a federal judge. “He was already writing and designing his own clothes, putting lapels on vests.” Lelyveld, another classmate, concurs: “He had an elegance particularly striking in a Harvard junior.” As a freshman, Seidel met the comfortably incarcerated Ezra Pound, who, in turn, arranged an introduction to T.S. Eliot, another St. Louis refugee.

In 1962, Robert Lowell, Louise Bogan, and Stanley Kunitz selected Seidel’s first collection, Final Solutions, for the 92nd Street Y’s inaugural Helen Burlin Memorial Award, which included a book deal with Atheneum Press. When Seidel, all of 26, was asked to make changes to several poems—the Y claimed they libeled Mamie Eisenhower, among others—he refused. The sponsor withdrew the prize, and the judges resigned in protest. The Times covered the flap, and Jason Epstein at Random House published the book.

The follow-up didn’t come for seventeen years. Shortly after Final Solutions, Seidel stopped writing. “Though I had written a lot, I had not found how to write a poem,” he says. “I simply had nothing to say.” In the interim, he inaugurated the scene at Elaine’s and became a father, certain that the authentic voice he was waiting for would come. He describes Sunrise, published in 1980, as “a push of a tomb door.”

“At her old apartment at 12, Rue de Seine/We lived like hummingbirds on nectar and oxygen.”

Ten books have followed, each, according to Poirier, “better than the one before.” The poems in Ooga-Booga are the richest yet and read like no one else’s: They’re surreal without being especially difficult, and utterly unpretentious, suffused with the peculiar American loneliness of Raymond Chandler. Even when writing about sex, Seidel sounds incurably alone. And the charges of elitism and starfucking fall apart as soon as one actually reads the poems—a lunchtime glass of Haut-Brion at Montrachet becomes a self-dissection, and Seidel is toughest on himself: “I’m sucking on the barrel of a crystal pistol / To get a bullet to my brain.”

Throughout there are passages of startling lyricism. In “Broadway Melody,” he watches an infirm couple leaving a diner, “spreading their wings in order to be more beautiful and more terrible.” “Barbados,” a nightmarish Diego Rivera mural of a poem, is the loveliest Seidel has written to date, and he’s perfected the subtle rhythms and rhymes that rocket the stanzas forward like his Ducati 916 SPS. While I can think of a more likable book of poems, I can scarcely imagine a better one.

The last poem, “Death of the Shah,” describes a recent trip to Ghana. Seidel’s wanderlust has taken him to remote places—when the American Museum of Natural History commissioned him to write a series of poems on the subject of the cosmos, to celebrate a new planetarium, he says he even lobbied Bob Kerrey to have NASA send him to space. When Seidel catches the incredulous look on my face, he adds, “I’m in terrific shape,” looking a little crestfallen. Later, he asks a favor: “Would you write about something more than just the beautiful women, fast motorcycles, and great clothes?” I promise I will try.