Although with regard to the past, when this is reported correctly what is brought out from the memory is not the events themselves (these are already past) but words conceived from the images of those events, which, in passing through the senses, have left as it were their footprints stamped upon the mind. My boyhood, for instance, which no longer exists, exists in time past, which no longer exists. But when I recollect the image of my boyhood and tell others about it, I am looking at this image in time present, because it still exists in my memory.

—St. Augustine of Hippo, Confessions, 398

Memory is the same as imagination.

—Giambattista Vico, New Science, 1725

NOTE: This profile of the allegedly fake memoirist Augusten Burroughs is based on real events. Dialogue has been compressed, and chronology has been changed for dramatic effect.

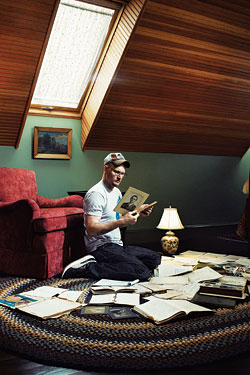

Augusten Burroughs travels between Amherst, Massachusetts, where he lives, and New York, where he keeps an apartment, in a hired black Town Car, so he can sit in the back and chew nicotine gum and watch Trauma: Life in the ER on his iPod. He has come down, this April afternoon, to walk me around his old neighborhood while I dredge his apparently superhuman memory in an effort to determine whether he is, as millions of readers seem to believe, one of the most honest men on the planet—someone willing to share unvarnished true-life details of his childhood statutory rape and the time he murdered a rat in cold blood in his bathtub—or whether, as others have alleged (some of them in a court of law), he is actually a gigantic liar. I know that his memory is superhuman because he told me so, last week, over lunch. “I can remember being 8 months old in my high chair,” he said, chewing nicotine gum between bites of a goat-cheese omelette. “I can remember learning to walk. I can remember the exact sound the wooden spoon made on the aluminum pot on the stove. I can remember that the lid of the pot had a little knob, putting it in my mouth like a nipple. I can remember my high chair’s tray: The metal was textured, it had peak-valley, peak-valley, peak-valley, a small design element, a striation.” Tomorrow he leaves for San Diego to give a speech to someone about something or other. He doesn’t remember. “I just show up and talk,” he says.

He does, indeed, show up and talk. In person, Burroughs has a focused analytical intelligence that doesn’t always come through in his writing, which tends to be emotional and therapeutic and often is written from the perspective of a child. In our first conversation, he gives me speeches about the neglected genius of middlebrow novelist Elizabeth Berg (“If she had a penis, she’d be John Updike”), the origins of southern manners among Belle Époque New York millionaires, and the ecstasy of quantum physics. (He’s particularly jazzed about a phenomenon called “entanglement,” in which photons at opposite ends of space seem to communicate instantaneously.) He says he can differentiate between the major brands of carbonated water (“Perrier has sharp, broken-glass bubbles; Calistoga’s are smaller”), as well as between real homeless people and college kids pretending to be homeless. “There’s that look you can’t replicate with eye shadow,” he says. He is, in person, almost the opposite of his textual persona: tall, athletic, and intense. In an effort not to look “pregnant” for the book tour for his new memoir, he’s been working out every day and recently broke his addiction to midnight bags of M&Ms. He is wearing, today, his publicity-tour uniform: jeans, black leather jacket, a blue T-shirt with some kind of Victorian woodcut on it, and a brown mesh trucker hat featuring an artsy cow. The biggest surprise, to me, is that he radiates trustworthiness: He seems open, unrushed, self-deprecating, and willing to discuss any subject with piercingly direct eye contact. He asks questions about my childhood, listens carefully to the answers, and follows up with more questions. He is unfailingly kind to waiters. His voice is dry, higher-pitched than I’d expected, and a little twangy, the product of growing up under highly educated southern parents in western Massachusetts. He puts an especially heavy accent on the word was: It comes out sounding like “wahz” or “waaaahz”—as if, even phonetically, the past requires disproportionate emphasis.

I find myself trusting Burroughs far more in person than I ever have in print—and yet I recognize in this trust yet another reason to doubt. Our meeting, after all, is just the first phase of a global marketing campaign whose success depends entirely on the spectacle of his honesty. Trust is the product for sale.

Burroughs and I are sitting looking out the big rectangular plate-glass window of an Equinox fitness center on the corner of Greenwich and 12th. The window is giant and perfectly clean and creates the illusion of containing the entirety of West Village foot traffic like fish in an aquarium. Although Burroughs no longer drinks, he collects lesser compulsions like little girls collect seashells, and he has been drawn to this spot by the lure of two converging addictions, one minor, one major. The minor addiction is Red Bull; they didn’t have it, so he settled for a Diet Coke. The major addiction is, as usual, Burroughs’s Big One, the master dependency around which all his minor dependencies (M&Ms, the Internet, French bulldogs, nicotine) seem to rotate in twitchy, continuous orbit—the source of pretty much all his wealth and fame and controversy: namely, his allegedly vivid, restless, overstuffed memory. He is giving it a light workout, here at the window, excavating some details mostly for my benefit. This, he says, is an ideal spot for reminiscence, “a very nutrient-dense area.” The gym is on the corner of Burroughs’s old street, which he hasn’t returned to in over ten years. He lived here in the West Village eighteen years ago, when he was 24. “All these little details come back when I’m here,” he says. “It’s like there’s a whole other time layered over this one. And the people that lived here still live here for me, still walk the streets.” He says he remembers, for instance, watching a painter—“navy shirt, white pants, brown belt, black boots”—painting a door across from his old apartment. “White drop cloth spread out over the stone steps,” he says. “The way the light hit him.”

My internal polygraph begins to twitch here, subtly, because what sort of freakishly bloated cortex retains, for eighteen years, the color of a random workman’s belt? This is exactly the kind of improbably authenticating detail Burroughs has been accused of inventing in his books—not a big deal on its own, perhaps, but patch enough of them together and your life story is suddenly more imagined than remembered. “The way the light hit him”? Seriously?

Burroughs says that, back when he was busy drinking himself to the brink of death in his apartment halfway down the block, this fitness center with its big glass window was an old movie theater called the Art Greenwich. He used to hang out in front of it with a crowd of homeless people, in a kind of informal apprenticeship. “I wasn’t doing it to be cool and have homeless friends,” he says. “I was doing it to see, How hard can this be? I thought it was inevitable I would become one of them.” They got to be such pals they’d do him favors. “They would see me going down to the subway, and all of a sudden there’d be this filthy hand slapping right in front of me, putting a token in.” (My polygraph spasms again: a bit Dickensian.) Burroughs fires up his synapses and describes, in detail, the look of the old theater’s lobby: its threadbare red carpeting, the off-kilter angle of its back corner, its glass door.

I ask him what movies he saw here.

“Lots,” he says, but he can’t come up with any names, just something about Robert De Niro as a pedophile on a boat with Juliette Lewis.

Village girls drift past the window in complicated boots. Burroughs points across the street to the diner where he used to have fat-soaked hangover breakfasts to try to absorb some of the alcohol before it reached his swollen liver. He tells me about miserable nights at a now-defunct gay bar called Uncle Charlie’s, a place “just exactly as loathsome as the name implies.” He remembers, vividly, the embarrassment of trying to sneak Hefty bags full of wine bottles down the stairs of his old building in the middle of the night. But he can’t remember which apartment he lived in.

“Something D, maybe?” he says.

At this, my polygraph sketches a quick profile of the Alps. Who can remember the color of a stranger’s belt, and the precise angle of the back corner of an old movie theater’s lobby, but not the number of his own apartment, or any of the movies he saw? What kind of memory is that?

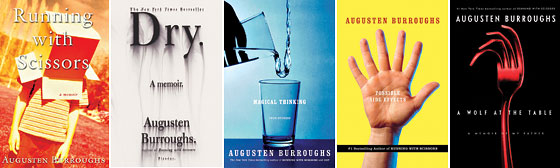

To describe Burroughs’s semi-mythic and exhaustively self-documented life is, at this point, deeply redundant. Over the last six years—as America reached and then passed the red-hot climax of its sadomasochistic affair with memoir—Burroughs has seemed determined to surpass all reasonable human limits of public self-disclosure. In that span, he has published five autobiographical books, and he supplements these with a blog, a MySpace page, and an elaborate promotional Website complete with emotive folk songs about his childhood and video of him kissing his dog. We know the names of not only his current pets (Bentley and the Cow) but also his childhood dogs (Cream, Brutus, Grover) and his dead guinea pig (Ernie). Burroughs’s new book, A Wolf at the Table, is being promoted as “his first memoir in five years”—a gem of self-canceling hype roughly equivalent to “her first wedding since last fall” or “his ninth bar mitzvah since he was 13.”

And yet somehow here we are. Burroughs was born Chris Robison in 1965, into legendarily unpromising circumstances. His mother was a suicidal bad poet, his father a sadistic, alcoholic philosophy professor. When the marriage flamed out, after years of enthusiastic mutual abuse, Burroughs commenced his world-famous adolescence, as described in his ubiquitous 2002 debut memoir, Running With Scissors: His mother abandoned him to her eccentric psychiatrist, a Santa Claus look-alike who searched for hidden messages in his own feces, excused himself during therapy sessions to visit his “masturbatorium,” and allowed Burroughs to have a sexual relationship with a 34-year-old man. (According, at least, to Scissors.) After escaping this madhouse in his late teens, Burroughs reinvented himself: He went to computer school, changed his name (Burroughs after a defunct computer, the Burroughs tabulator; Augusten because it “sounded classic—but then, when you looked at it twice, absolutely unfamiliar”), and commenced the second, only mildly less world-famous phase of his life, described in his second memoir, Dry (2003): He landed a high-paying job in advertising, moved to New York, blew his money and health on alcohol and drugs, went to rehab, and lost his best friend, Pighead, to AIDS. After all of this tragedy, Burroughs discovered the circular salvation of the memoir. He was rescued from homelessness, alcoholism, crack, and abuse—in short, from everything depicted in his books—by the books themselves.

Today, Burroughs is the last of the big-game memoirists, targeted but still on his feet, still profitably working the cud of his dysfunctional youth, still memoiring, against all odds, under the vengeful glare of Oprah and her increasingly skeptical public. As the culture of memoir has imploded over the last few years—as JT LeRoy dissolved into some kind of conceptual-art project about Truth in Media, as James Frey suffered the most visible public flogging in the long history of global torture, as Margaret “Gangland” Seltzer was outed by her own sister as a pampered suburbanite, as Misha Defonseca admitted that she was neither a Holocaust survivor nor raised by wolves—Burroughs sat at his laptop, undeterred, furiously masticating his chemical gum, and claimed, with a perfectly straight face, to be faithfully transcribing the honest-to-God events of his past.

When Burroughs writes, he tells me, he drifts into a kind of shamanistic memory trance that allows him to travel freely through time. He never stops to look at what he’s typing, which he says would only distract him. Instead, his eyes glaze over, and he stares absently at the small aluminum strip between his laptop’s keyboard and screen. “When I am writing,” he says, “I am there. I’m there. I never, ever, in any of my books, ever, have thought, ‘Now, how would I have talked?’ That is not how I write. It feels like I just go back and I’m there. It’s like a movie. It’s extremely vivid. I’m a monkey at a typewriter, writing about the time it got M&Ms, and the time a blue M&M came out instead of a red one.” Like Proust, he works in bed, propped up on some pillows. He feels terror, excitement, and sadness; he cries. It’s more like a séance than a job.

Burroughs’s publicist has set us up for dinner at an unlikely venue, a tiny West Village cave with tastefully arranged paparazzi outside that also happens to be owned (and frequented) by Graydon Carter, whose magazine, Vanity Fair, published a long article about the Running With Scissors lawsuit—the biggest dent yet in Burroughs’s public credibility. In 2005, the family depicted in Scissors sued Burroughs for libel; the case settled last summer, when Burroughs and his publisher agreed to publish the book with a disclaimer recognizing that the family had a different perspective of the events described. (Burroughs called it “a victory for all memoirists.”) When I mention the Vanity Fair connection, he shrugs. He’s still wearing his book-publicity uniform, except this time his hat has a pig on it instead of a cow, and his T-shirt is a lighter shade of blue. When we sit down, he takes off his leather jacket to reveal a pair of tattoos running up each forearm: on his left arm, a mess of winding filigree, on his right, the phrase CICATRIX MANET—Latin for “The scar remains.” (He says he also has a spiral tattooed on the back of his shoulder, to remind him not to drink.) He has a way of shrinking already-small New York restaurants. His voice, as it locks into one of his speeches, tends to rise in volume to match the intensity of his thought, and to find its way into distant corners. The dignified elderly couple at the next table leaves not long after we sit down.

Burroughs says he never read the Vanity Fair article—in general, he avoids reading his press—but that it doesn’t bother him. “It didn’t have the impact they thought it would,” he says. “No one mentioned it to me. Only reporters. It didn’t build. It was like a nothing. There was nothing there.” I ask if he’d mind, given that we’re at Vanity Fair’s unofficial headquarters, responding to the article’s main points. He agrees.

I run through the accusations one by one: that Burroughs fudged the book’s timeline; that he never saw a 6-year-old nicknamed “Poo Bear” poop under the family piano; that there was no masturbatorium; that a shock-therapy machine the kids played with was actually an old vacuum cleaner missing a wheel; that Burroughs and one of the children did not tear down the kitchen ceiling. He responds, vehemently, to every charge.

“Well, no, that’s not true at all,” he says. “God no, I lived with them far longer. A year and a half, they said that? That’s weird. … It was not an old vac—I know a shock-therapy machine from an old vacuum cleaner, for God’s sake! That’s weird, that’s just a weird comment … Why would they deny that he has a masturbatorium? How does that harm them? If he were alive, he’d be the first person to tell you where it was. He’d sit right here and say of course it was my masturbatorium. So it’s just weird to me … Wow. Wow! I’m flabbergasted. Wow.”

His voice begins to fill the little restaurant.

As I watch Burroughs react, my polygraph needle begins to tremble again. Outraged denial is, of course, a reasonable response for an honest writer accused of lying. But is it even remotely possible that, after a well-publicized two-year trial in which his career and reputation hung in the balance, these allegations would come as a surprise to him? Can he possibly be “flabbergasted” by anything I’ve said?

I ask him if these accusations came up in court. He says he doesn’t remember. A minute later he says he thinks they probably did.

Soon he is borderline shouting about how ridiculous it would be for a writer seeking mainstream fame to describe not only a gay sexual relationship between a man and a young boy but “anal penetration!”

The new diners at the table next to us, a pair of quiet young gentlemen in nice sweaters, pause momentarily from their conversation about a Paris Review party.

I ask Burroughs if all of this makes him angry.

“It doesn’t make me angry,” he says. “It makes me feel incredulous. It’s a very arbitrary list of things. They’re reaching, grasping at straws. What it comes down to is they’re trying to portray me as a liar and say, ‘No, it wasn’t sunny that day, it was rainy. He lied. We want our money.’ ”

Does it ever make him doubt, even for a second, his account of things—or wonder if he might have just misunderstood as a kid?

“Oh, God, no,” he says. “How can I explain this? It’s not like writing about high school and talking about what yard line the cheerleaders stood at. High school for the most part is unexceptional. These were absolutely extraordinary circumstances. I mean, the terror of my mother going psychotic the way she did, being unable to raise me, and then the wildness of living in this house—it burns into your brain. If you had been on the Titanic when it sank, I promise you, I bet you every penny I have, you would know exactly what you were wearing, exactly who was standing next to you, what they were wearing, exactly what people were saying. You would know precisely which side of the lifeboat you climbed into, you would remember if you took your life jacket off or if you left it on, you would remember exactly how that ship sank. You just would. But if you took the Titanic and it didn’t sink, how much would you really remember? So it doesn’t make me second-guess my recollection of it. I don’t see how I could be wrong. It isn’t. It isn’t. I bet my life on it. I bet my life on it.”

The maître d’ comes over and asks him to lower his voice.

“I did not sit down and cleverly think of a story that I thought would be gripping and make me lots of money and famous,” he continues. “I sit down and I go back and I write the stories from my life. It is that simple. All the rest of it I leave to other people to talk about and debate.”

We do not order dessert.

The tension between “actual” memory and our translation of that memory into words is not, despite the public’s perennially fresh outrage, a new problem, nor one that has an easy answer. Every memoir depends on a loose cognitive partnership between notoriously sketchy processes: the subjectivity of memory itself, the spotty and biased power of recall, the translation of images into language. Memory is chaotic, nonsequential, and spotty; marketable narrative is easy, clean, and quick. You might say, in fact, that a certain low-grade lying basically defines the genre, and always has, all the way back to the very first memoirist: Saint Augustine, the fourth-century bishop of Hippo, who confessed, in his Confessions, that he was recording “not the events themselves … but words conceived from the images of those events.” (When I asked Burroughs if he got his first name from the memoiring saint, he said that if he had he “should be taken out back and shot in the fucking head. That would just be so horribly pretentious.”)

All of this is, by now, a very familiar can of worms to Augusten Burroughs. “We’re a binge culture,” he says. “The media will get on one topic and stay on that topic forever. I’m going to be asked about the veracity of my memoirs and the state of memoir when I’m 65. It will never, ever stop.” Still, he’s happy to make his position clear. He insists that Running With Scissors preceded the memoir boom—and that now, after a publishing craze brought on largely by his own success, the genre has spun out of control. “It’s just exactly like fucking puppy-mill puppies,” he says. “All of a sudden a dog will win Westminster and it will become the ‘It’ dog and you’ll see it in New York everywhere and it’ll be in all the pet stores, and what happens is you start off with a really solid, good breed—poodle is a perfect example. Very stable dogs, very good with children, very smart, the smartest breed. Very loyal. And then they get bred, and they get inbred, and they get inbred, and the genetics become weaker and weaker and you get hip dysplasia. Until what you end up with can’t even be called a poodle. That’s kind of what’s happened with memoir.”

“It doesn’t make me angry. It makes me feel incredulous. They’re reaching, grasping at straws. What it comes down to is they’re trying to portray me as a liar and say, ‘No, it wasn’t sunny that day, it was rainy. He lied. We want our money.’ ”

Burroughs says he rarely reads other memoirs, but when he does he expects the truth. “I find the privileged white girl writing about gangland morally corrupt,” he says. “I have a problem with that. I would feel manipulated. JT LeRoy? I would feel really violated. People sort of think now, not ‘Do I have a story to tell?’ but ‘Can I think of a story I could write and call a memoir?’ And it’s unfortunate because it becomes the focus in the media, and as a result I think there are a lot of incredible stories that may get overlooked because of the big memoir scandals. I mean, how would Bastard Out of Carolina do today, you know?”

(Bastard Out of Carolina, just for the record, is a novel.)

Burroughs responds to charges of fakery with a denial so bulletproof it almost feels suspicious in itself—it suggests either supreme heroic conviction or a deep, possibly even unconscious, self-deception. He insists, always, that he’s telling the absolute truth, even about the details of events that happened 30 years ago. And the bedrock of this defense is always his bionic memory, in which he seems to have total faith.

“I guess it’s unusual,” he says. “My brother thinks it’s because I have a little Asperger’s like him, and it’s an Aspergian trait. It’s an incredible benefit when I’m writing about my past. But it’s also a disadvantage in that it’s incredibly vivid.”

At the center of the skepticism about Burroughs’s credibility, even among his admirers, is his work’s relentlessly scenic quality. He never recounts dialogue in general terms or describes incidents vaguely. Even the most banal exchanges are quoted verbatim. In the new book, instead of summarizing a 30-year-old conversation with his mother, Burroughs re-creates it, word by word, gesture by gesture, to a degree that seems humanly impossible.

When I ask him how this works, he is open and adamant.

“Did I get every syllable right?” he says. “No, probably not. But that’s the gist of it. That’s how she spoke. Those are her inflections. And if it’s not exactly word for word, it’s certainly nobody else, and it’s certainly not my words in her mouth. Was there sun streaming in that day, the actual day that she told me about her marriage? Was the sun at a 47-degree angle? How the fuck would I know? But that’s my memory of that period with my mother painting, when the sun was low in the sky like that. I took a sky from one of hundreds of days that were all the same. But that’s the painting. I have it downstairs in my house. That’s the smell, that turpentine smell. If it wasn’t Tosca on the stereo it was La Traviata.

“The thing with memoir is that it’s not court stenography, and it shouldn’t be. We have video for that. We have YouTube for that. And I don’t understand the criticism. This is not a trial, where I’m recounting a murder and every action must be photographed and documented and measured with a tape measure. It’s a life.

“It’s a very peculiar fixation. It’s like asking the orange: ‘Why? Why do you have the pits? Why aren’t you smooth like the apple? Why? Why do you have to have the little indentations? No one licks the indentations, no one hides anything in the indentations, it’s not like those little indentations are useful. Why do you have them?’ ”

Burroughs, it should be said, does seem to have an uncanny knack for voices. I notice that, whenever he tells a story about his father, he drops into an impromptu little Dad impression: a slow, low, doltish voice with a southern accent. (“Wul, son, y’know, long time ago. Dudn’t matter.”) When I ask him if this is really what his father sounded like, instead of answering normally, he breaks eye contact, and his gaze drifts into some kind of wormhole several light-years behind my left ear, and he answers my question by channeling his father himself:

“Uh, uh, a better … impression, uh, of my father,” he says, in a halting, flat voice. “Wou-would, would, would be—like I say, uh, a better, impression, of my fa—if I were to try, if I were to attempt an impression of my father.” He keeps staring blankly at the wall of the restaurant. “What I would do, first, primarily, is, A, I would try to—attempt—the cadence, with which he spoke. And then further if I was, again, engaging in this impression of my father, B, I would try—and though I may fail, like I say, I would try, but I may fail, to imitate: the tone, of his voice.”

His eyes click back over to mine. “That’s my father,” he says.

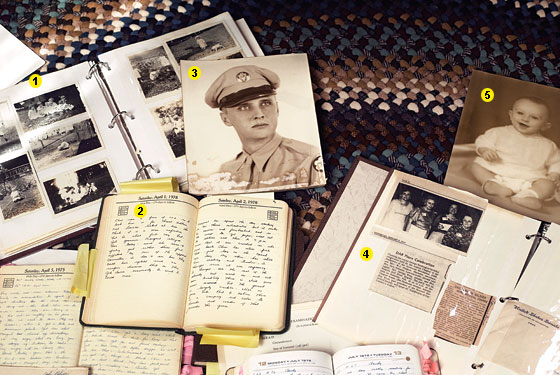

A Wolf at the Table is essentially the prequel to Running With Scissors, although it’s significantly more painful and probably two-thirds less funny. It tells the story of the young Augusten’s suffering at the hands of his sadistic father, a dry-lipped, black-toothed, lesion-plagued professor of logic and ethics. (He died three years ago.) The book swings between scenes of pathos and terror. Preadolescent Augusten, desperate for affection, stuffs his father’s old clothes with pillows and cuddles with them at night; Dad murders Augusten’s guinea pig, magically retrains the family dog to be vicious, and tries to kill his son in a car accident. Burroughs often describes his writing in therapeutic terms, as “venting,” or “swatting branches out of the way in a dense forest”; often, his books begin as journal entries (Dry was harvested from an 1,800-page computer file called “mess, collected”), and they tend to have the strengths and weaknesses of a diary: They can be artless, repetitive, meandering, and mawkish, but also immediate, heartfelt, connective, and sympathetic.

I talk to Burroughs’s older brother, John Elder Robison, about his brother’s version of events. Although he and Burroughs grew up largely apart, they are now neighbors in Amherst. Robison tells me, in a voice that sounds 100 percent identical to Burroughs’s impression of it, that he and his brother are opposites. Owing to his Asperger’s, he tends to be “flat and logical,” while Burroughs is “entirely governed by emotion.” (As Burroughs later puts it, “My brother has the emotion of an IBM laptop computer.”) Because of this, they often experience the same events in radically different ways. Still, Robison insists that his brother is honest.

“I really feel strongly that people are critical of my brother because he’s so emotional. But that absolutely does not mean it’s made up. Just because somebody dramatizes the emotional content of something in their mind does not make it false.”

Burroughs’s mother has said that she, too, remembers some things differently. She’s currently working on her own memoir. Robison published his, Look Me in the Eye, last year.

After dinner, Burroughs and I walk in continuous disorienting loops around the Village while he extracts more baubles from his memory-hoard. We pass his favorite independent bookstore, which is now a Chase bank. He tells me about the time he met Academy Award winner Linda Hunt while holding a fresh handful of dog feces. (“And I’m thinking, ‘Okay, so what are the chances of just an average guy meeting any Academy Award winner in his life? And what are the chances further of meeting that Academy Award winner while holding dog shit? And what are the chances that they would be the only dwarf Academy Award winner?’ It just seemed spectacular.”) We pass a real-estate agency that used to be a corner store with an oddly distinctive smell—like “sour milk and earth,” he says, “but somehow neither.” I ask Burroughs what memoir he’s going to write next. Growing up with his brother? Nursing his bulldog back from a spinal injury? Overcoming his addiction to M&Ms?

He says he might be done. He wants to go back to fiction, which he says always feels like an adventure. (His first book was the novel Sellevision, which he wrote in seven days.) “I’ll always write about myself. I just don’t know if I’ll always publish what I write.”

I ask what this novel might be about.

“I should write about the son of a Connecticut senator who writes about a dysfunctional childhood living with a psychiatrist,” he says. “It would be very postmodern.”

Five days after our last meeting, I send Burroughs an e-mail thanking him for his time and warning that I might have some follow-up questions. He responds, quickly, to say that he enjoyed it, then adds, apparently as an afterthought: “what’s that little white dot on your front left tooth? a filling?” I’m impressed: The bottom half of that tooth is fake, a mutual gift from my older brother and the concrete edge of our apartment complex’s swimming pool when I was 8. One little spot stands out. I haven’t noticed or thought about it in years. I write back and tell him so. As I wait for a response, I start to wonder about his motives. Was he actually curious, or was this just some kind of guerrilla-marketing campaign to tout his astounding powers of observation and recall? Again, he writes back quickly, recommending that I see his dentist: “of course, it’s not like you have some glaring tooth problem. it’s a tiny thing. most people wouldn’t even notice. just like most people might notice your glasses? but not that they say Nautica along the temple.” I take off my glasses: It’s true. This is also impressive, but a little flagrantly calculated for my taste. I begin to doubt his powers altogether. For all I know, he’s just memorized a couple of trivial details in order to unleash them on me at exactly this kind of strategic moment.

Now that he’s being brazen, I decide to test him: What else does he remember?

He responds with a detailed 1,200-word recap of our time together: exact phrases we spoke at specific intersections and the cars that passed as we said them; which hand I’d used to straighten my notes at the table; the names of my children; the design of my watch face and wedding ring (“either white gold or platinum … two ridges, or channels—one on top, one on the bottom”). Having been there myself, and having just relived the entire experience via five hours of recorded conversation, I find his account (although he gets a word or two wrong) very persuasive.

He even remembers a story I told him about fainting from dehydration in a grocery store in the middle of Queens. He admits that, as I was telling it, he was doubting some of its details, wondering if I’d allowed myself to embellish the story over the years, eventually even revising my memory to match the more dramatic version. And he was right: I had.