“I don’t really think of myself as an outlier.”

It’s a Friday afternoon in mid-October, one month before his new book about incredibly successful people like Bill Gates and the Beatles and Mozart—the people whom he calls outliers—arrives in bookstores, and Malcolm Gladwell is insisting that, honestly, he doesn’t have anything at all in common with his subjects. “At the end of the day,” he says, “I’m just a journalist.”

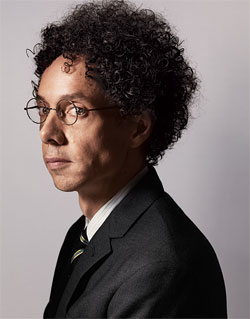

Gladwell is offering this modest self-assessment while seated at the kitchen table of the apartment he rents in a stately West Village townhouse. He’s wearing jeans and one of those wickable running shirts, which fits snugly over his thin frame. His hazel eyes are red-rimmed. His trademark Afro, which he had cut about a month ago, is at frizz-level yellow. He looks, in short, like a caricature of Malcolm Gladwell. He is a well-known figure around his neighborhood, fond of tapping away on his laptop in coffee shops and cafés. His writer’s life is part anachronistic, part futuristic. His Lexus IS—a car, he concedes, he rarely drives—is parked down the street in the space he pays a small fortune to lease. A couple of miles north in Times Square are Gladwell’s editors at The New Yorker, who don’t see him in the office very often—owing to his self-professed “aversion to midtown”—but who grant him a license to write about whatever he chooses and accommodate him with couriers to pick up his fact-checking materials, lest he be forced to overcome that aversion. Not far from The New Yorker are the offices of Little, Brown—the publisher of Gladwell’s two best-selling books, The Tipping Point and Blink—which paid him a rumored $4 million for Outliers. (“The hardcover of Blink sold three times what the hardcover of Tipping Point did,” says Geoff Shandler, Little, Brown’s editor-in-chief, “so his audience has grown and grown.”) Across the river in New Jersey is the Leigh Bureau, which fields Gladwell’s speaking requests and negotiates his stratospheric fees. (“He was by far the most expensive speaker we ever contracted,” says Charles Cohen, the president of a dental-supply company, whose trade group paid Gladwell $80,000 to address its annual meeting. “There wasn’t one person afterwards who said he wasn’t worth the money.”) And then, in New York and New Jersey and all over the United States, there are the booksellers, who are hoping that, amid fears of a global recession, Outliers will prompt their customers to do that thing that’s become a rarity these days—plunk down $28—and thus offer a slim reed of hope to the sagging publishing industry. (“I don’t care that it’s Little, Brown’s book,” says one rival publishing executive. “We all desperately need some good news.”)

And yet, back in Gladwell’s kitchen, as he sits amid the Miele appliances and sips from a cup of water, he maintains the pose of humble scrivener. He professes discomfort, even a bit of guilt, about the fame and fortune he has attained, and his new book, a more self-consciously serious work than his previous two, is, in some ways, an attempt to address these conflicted feelings. But if in print he traffics in big ideas and confident declarations, in person he is a master of gentle self-deprecation and understatement. “I spend my time talking to people who tell me things, and then I write them down,” he says. “I’m necessarily parasitic in a way.” He pauses, as if to consider whether he’s protesting too much. “I have done well as a parasite,” he goes on. “But I’m still a parasite.”

Of course, no amount of self-deprecation can mask Gladwell’s phenomenal success. Since the 2000 publication of The Tipping Point, he has been less a journalist than, as Fast Company once deemed him, “a rock star, a spiritual leader, a stud.” Business executives seek him out for his insights, adoring fans stop him on the street to shake his hand, and other writers strive to emulate the genre he essentially pioneered—the idea-driven narrative that upends the way we think about everything from cigarettes to ketchup. “We get scores of proposals each year promising a Gladwellian take on the world,” says Shandler. “I don’t know any other author who has spawned that kind of adjective in nonfiction.” One Condé Nast editor, struggling to come up with another writer who has occupied as singular a place on the media landscape as Gladwell currently does, finally offers, “It’s kind of Norman Maileresque, isn’t it?” Forty years ago, all the sad young literary men were trying to find their own armies of the night to mythologize; now they search for their own hipster footwear trend to deconstruct.

Gladwell’s modesty isn’t entirely a pose. As he’s the first to acknowledge, his writing largely consists of taking the work of academics and translating it in a way that makes it understandable—and entertaining—to a lay audience. His job, as he describes it, “is to be this intermediary between the academic world and the public.” That has led some critics to dub him not so much a parasite as a pilferer. The Nobel-laureate economist Thomas Schelling, who developed the “tipping point” model some three decades before Gladwell made it part of our everyday vocabulary, has complained, “I think what he leaves people with is not that scientists are doing some interesting work but that Malcolm Gladwell has a couple of good ideas.” Schelling’s, however, seems to be a minority opinion. Most academics whose work Gladwell uses are just grateful for the recognition. In the last couple of years, both the American Psychological Association and the American Sociological Association have given him awards.

The bigger criticism of Gladwell is not that he’s unoriginal but that he’s unserious—that he takes substantive academic work and applies it to frivolous things (epidemiology and Hush Puppies, anyone?). While such an approach may endear him to business elites, it often infuriates cultural and political ones. Leon Wieseltier, the literary editor of The New Republic, has said, “What Gladwell is marketing is nothing but marketing—the marketer’s view of the world. But that view of the world is, I’m afraid, idiotic.” The judge and legal scholar Richard Posner, in a scathing review of Blink for TNR, complained that it was “written like a book intended for people who do not read books.” Meanwhile, Carlin Romano, the influential literary critic for the Philadelphia Inquirer, used his review of Blink to give its author a hazing and an ultimatum: “Gladwell, one fears, has come to his own tipping point, or—to be fuddy-duddy—fork in the road. This way, guru. That way, serious writer.”

Gladwell tends to dismiss this line of attack. (“It was a sending a man to do a boy’s work,” he says of Posner’s review. “The guy’s like this legal Einstein, and he’s slumming it with Blink?”) But when he talks about his previous books, he sometimes sounds as if he agrees with his critics. “When I read Tipping Point now, it does seem more like a product of a lighter time,” he concedes. “I was really interested in marketing at the time, and that’s not that weighty an issue.” Blink, he says, “is very kind of distant. It’s, ‘This is a lot of cool stuff! Do with it as you will!’ ”

For all of his pop sensibility, Gladwell sees himself as something of a fuddy-duddy. If, as Michael Kinsley once observed, Al Gore was an old person’s idea of a young person, then Gladwell is a young person’s idea of an old person’s idea of a young person. Beneath the crazy hair, the slobby-chic clothes, and the buzzword-filled vocabulary is an old-fashioned guy who grew up among Mennonites in rural Ontario, didn’t have a TV until he was 23, and still prefers to do most of his research at the NYU library. Google is something of a personal hobbyhorse: “Google is the answer to the problem we didn’t have. It doesn’t tell you what’s interesting or what’s important. There’s still more in the library than there is on Google.”

Gladwell’s friends insist that he doesn’t court fame, or enjoy it. “I think he tries to insulate himself in such a way that his life is as normal as possible,” says Jacob Weisberg, the editor-in-chief of the Slate Group. Once a regular at New York media parties, the 45-year-old Gladwell does most of his socializing these days in more intimate settings, including a regular biweekly “boys’ night out” dinner he has with Weisberg and a handful of other close friends, including comedy writer Steve Sherrill and Columbia law professor Tadi Farhadian (the only regular woman). “It’s weird to be recognized by someone you don’t know,” Gladwell says. “The asymmetry of it is unsettling.”

What’s a put-upon guru to do? Gladwell isn’t about to give back his advances or stop speaking at business conferences, but he is trying to take his writing in a more meaningful direction. Where he once focused on cool-hunting and T-shirts in his New Yorker articles, now it’s IQ tests and pension systems. “There is a kind of underlying social vision in a lot of his pieces,” says Henry Finder, his editor at the magazine. “The basic vision says how we fare in life isn’t just determined by ourselves and our character, it’s determined by a lot of other things that are beyond our control.” Gladwell has expanded that social vision into a book that he describes as “more political” and “a little angrier” than his previous efforts. “The interesting part of this now is trying to figure out what you do with the idea,” he says, explaining the new approach he took with Outliers, “as opposed to before, where the interesting part was just explaining the idea.” Bruce Headlam, a childhood friend of Gladwell’s who’s now an editor at the New York Times, calls Outliers “the book that’s closest to Malcolm’s heart.”

“When I wrote Tipping Point, my expectation was it would be read by my mom and that was it,” Gladwell says. “I had no notion I was creating a kind of public document. Now I realize I have a bit of a podium, so it seems silly to put the podium to waste.” Which raises the question: With his new book that purports to tell “the story of success,” has Gladwell finally found an idea substantial enough to justify his own?

Outliers is at once Gladwell’s least and most ambitious book. Unlike The Tipping Point and Blink, which took their counterintuitiveness to extremes, the conventional wisdom Gladwell seeks to demolish in Outliers isn’t even really CW anymore. Is there anyone who still believes that “success is exclusively a matter of individual merit,” which is how Gladwell describes his straw man? And yet, as Gladwell examines all the things other than individual merit—the “hidden advantages and extraordinary opportunities and cultural legacies”—that produce hockey stars and software billionaires and math geniuses, he builds a brief for a massive reorganization of social structures and institutions that will give people who don’t have those advantages and opportunities and legacies an equal shot at success.

Consider, for instance, those hockey stars. Relying on the work of a Canadian psychologist who noticed that a disproportionate number of elite hockey players in his country were born in the first half of the year, Gladwell explains what academics call the relative-age effect, by which an initial advantage attributable to age gets turned into a more profound advantage over time. Because Canada’s eligibility cutoff for junior hockey is January 1, Gladwell writes, “a boy who turns 10 on January 2, then, could be playing alongside someone who doesn’t turn 10 until the end of the year.” You can guess at that age, when the differences in physical maturity are so great, which one of those kids is going to make the league all-star team. Once on that all-star team, the January 2 kid starts practicing more, getting better coaching, and playing against tougher competition—so much so that by the time he’s, say, 14, he’s not just older than the kid with the December 30 birthday, he’s better. The solution? Double the number of junior hockey leagues—some for kids born in the first half of the year, others for kids born in the second half. Or, to apply the principle to something a bit more consequential (to non-Canadians, at least), Gladwell suggests that elementary and middle schools put students with January through April birthdays in one class, the May through August birthdays in another, and those with September through December in a third, in order “to level the playing field for those who—through no fault of their own—have been dealt a big disadvantage.”

“The book’s saying, ‘Great people aren’t so great,’ ” Gladwell says. “Their own greatness is not the salient fact about them.”

Or take the case of Bill Gates. Gladwell cites a body of research finding that the “magic number for true expertise” is 10,000 hours of practice. “Practice isn’t the thing you do once you’re good,” Gladwell writes. “It’s the thing you do that makes you good.” Gladwell shows how Gates accumulated his 10,000 hours while in middle and high school in Seattle thanks to a series of nine incredibly fortunate opportunities—ranging from the fact that his private school had a computer club with access to (and money for) a sophisticated computer, to his childhood home’s proximity to the University of Washington, where he had access to an even more sophisticated computer. “By the time Gates dropped out of Harvard after his sophomore year to try his hand at his own computer software company,” Gladwell writes, “he’d been programming practically nonstop for seven consecutive years. He was way past 10,000 hours.” Yes, Gates is obviously brilliant, Gladwell concludes, but without the lucky breaks he had as a kid, he never could have had the opportunity to fulfill the true potential of that brilliance. How many similarly brilliant people never get that opportunity?

And then there are the math geniuses who, as anyone can’t help noticing, are disproportionately Asian. Citing the work of an educational researcher at the University of Pennsylvania, Gladwell attributes this phenomenon not to some innate mathematical ability that Asians possess but to the fact that children in Asian countries are willing to work longer and harder than their Western counterparts. That willingness, Gladwell continues, is due to a cultural legacy of hard work that stems from the cultivation of rice. Turning to a historian who studies ancient Chinese peasant proverbs, Gladwell marvels at what Chinese rice farmers used to tell one another: “No one who can rise before dawn 360 days a year fails to make his family rich.” Contrast that legacy with the one derived from Western agriculture—which holds that some fields be left fallow rather than be cultivated 360 days a year and which, by extension, led to the creation of an education system that allowed students to be left fallow for periods, like summer vacation. For American students from wealthy homes, summer vacation isn’t a problem; but, citing the research of a Johns Hopkins sociologist, Gladwell shows that it’s a profound handicap for students from poor homes, who actually outlearn their rich counterparts during the school year but then fall behind them when school lets out. “For its poorest students, America doesn’t have a school problem,” Gladwell concludes. “It has a summer-vacation problem.” So how to close the gap between rich and poor students? Get rid of summer vacation in inner-city schools.

Outliers is filled with those sorts of diagnoses and prescriptions. It’s a book that celebrates the great man, then, as politely as possible, cuts him down to size. “I’m one of those people who started watching golf, even though I’ve never picked up a golf ball in my life, when Tiger Woods started winning, because he’s just so extraordinarily compelling,” Gladwell says. “There is something inherently interesting about exploring a topic through the lens of these people, these outlier types, who are off the charts. The book’s saying, ‘Great people aren’t so great. Their own greatness is not the salient fact about them. It’s the kind of fortunate mix of opportunities they’ve been given.’ So I feel like, yeah, we know that, but we don’t act on it, so that’s why I think it’s worth repeating, because it’s one of those little truths that kind of dribbles away when it comes time for action.”

As for determining that action, Outliers moves away from the animating spirit of Gladwell’s previous books that led the New York Times to call him the “Dale Carnegie … of the iPod generation.” Gone, for the most part, are the cutesy buzzwords—there’s no place for “mavens” and “connectors” and “salesmen” in Gladwell’s story of success, and no amount of “thin-slicing” will help someone overcome relative-age disadvantage. “This is very specifically not a self-help book,” Gladwell says. “It’s a book that’s very much about collective and social organized change. I am explicitly turning my back on, I think, these kind of empty models that say, you know, you can be whatever you want to be. Well, actually, you can’t be whatever you want to be. The world decides what you can and can’t be. And the appropriate place to provide opportunities is at the world level, not the individual level.” With his last book, Gladwell sought to eliminate the focus group; with this one, he wants to eradicate poverty.

How does Gladwell explain his own success? He offers a preface of sorts to it in the final chapter of Outliers when he tells the story of his mother, Joyce, a psychotherapist who—through hard work and the relative privilege of her light skin and her own parents’ sacrifice and, finally, sheer luck—made it from a tiny village in Jamaica to an Anglican boarding school to University College in London, where she met the Englishman named Graham Gladwell who became her husband.

Malcolm grew up in a tiny Ontario farm town called Elmira, because his father, a math professor at the University of Waterloo, wanted to live in the countryside. “We get three or four sheep every spring, and they keep the grass down among the fields,” Graham says, “and they then get brought to the butcher in the fall.” At home, Gladwell’s parents, both Presbyterian, made Malcolm and his two older brothers do Bible study each night and then read them books like A Tale of Two Cities. (One brother is now an elementary-school principal in London, Ontario; the other works for a chicken-processing company in Kitchener.) At his small country school, which was made up mostly of farm kids, Gladwell made two similarly precocious friends, Bruce Headlam and Terry Martin, who is now a professor of Russian history at Harvard. “It was curious good fortune,” Gladwell says of finding Headlam and Martin, sort of like Gates’s going to a school that had a computer club. “Without those two, I wouldn’t be here today.”

In high school and then at the University of Toronto, Gladwell immersed himself in conservative politics, putting a Reagan poster on his wall and naming his plant Buckley (as in William F.). After failing to get a job in advertising, he landed at the right-wing American Spectator, which eventually led to a reporter position at the Washington Post in 1987. “That’s where I got my 10,000 hours,” he says of the ten years he spent at the paper covering business, science, and eventually New York. “People today write a lot, they write these blogs and things, but in all that research on 10,000 hours, they talk about deliberate practice. And the thing about a newspaper is, you have an editor … who’s saying ‘No, this doesn’t work, go back and do this.’ If I’d come up today”—when newspapers are doing more firing than hiring—“it’s very doubtful I would have been in such a supportive learning environment.” In 1996, with his 10,000 hours under his belt, he was hired by The New Yorker as a staff writer, which Gladwell says was his biggest break. “The great transition in my life was not writing Tipping Point. It was moving to The New Yorker. Once you’re at The New Yorker, that’s what opens the doors.”

Ever faithful to his big new idea, Gladwell continues to attribute his success to everything and everyone but himself. “As gifted as he is,” says New Yorker editor David Remnick, “I think he knows that there is a dimension to his success of a man catching lightning in a bottle, of crazy fortune.” More than luck, though, Gladwell credits the academics whose work he bases his own on. A couple years ago, a business professor took to the pages of the Journal of Management Inquiry to urge his fellow academics to do more popular writing and thus “put Malcolm Gladwell out of business”—which didn’t trouble Gladwell in the least: “If that was the condition under which I would be put out of business, I’d be delighted.” Indeed, sometimes Gladwell almost sounds tortured about his success, since it does seem to come at the expense of those whom he credits for making it possible. “If the spotlight should be anywhere, it should be on the originator of the idea,” he says. “I try to give credit whenever I can. And sometimes you fail, sometimes you fail because of your own sloppiness, and sometimes you fail because people don’t pick up on the credit … because necessarily, the figurehead-y person with the crazy hair giving the talk, even if he tries to give credit, it doesn’t stick. And I worry about that. In fact, that’s not fair. But there’s nothing—no, there isn’t nothing—but there’s a limited amount I can do. It’s a function of the way people receive knowledge.”

Of course, Gladwell’s description of himself as a parasite serves as a handy defense when his work comes under fire. Two years ago, after the economics blogger Megan McArdle criticized Gladwell for attributing in a New Yorker article Ireland’s success as the “Celtic Tiger” to declining birthrates, he responded on his blog that McArdle had the wrong guy—and did it, rather strangely, in the third person. “ ‘Gladwell’ does not attribute Irish success to falling birthrates,” he groused. “David Bloom and David Canning do. Gladwell is a journalist. Bloom and Canning are two exceedingly prestigious economists at Harvard, who are considered world experts in the field of demography and economics.”

“When I wrote ‘Tipping Point,’ my expectation was it would be read by my mom and that was it. Now I realize I have a bit of a podium, so it seems silly to put it to waste.”

When Gladwell’s critics themselves are world experts—as was the case when New York Times business writer Joe Nocera went after Gladwell for “conflat[ing] fraud with overvaluation” in a New Yorker article that argued that Enron’s misdeeds were hidden in plain sight—Gladwell retreats to the defense that his writing is merely meant to be provocative. “I don’t think it’s proper for someone in my position to be a definitive voice,” he says. “These books and New Yorker articles are conversation starters.”

Henry Finder charitably says of the instances in which Gladwell has been wrong: “There’s a great line of Wallace Stevens: ‘Sometimes you must go too far to see what would suffice.’ ”

Gladwell describes much of his writing as “playful, intellectual explorations” of ideas. But these explorations often result in Gladwell being decidedly agnostic about the ideas he’s propagating. His willingness to quickly concede error—“Much the mensch,” the Slate media critic Jack Shafer wrote of Gladwell after he admitted being wrong about the subject of women and estrogen—can also be read as a lack of conviction. If ideas are just an occasion for fun, Gladwell seems to be saying, who needs to believe in them? Which is the biggest reason why Outliers is such a break from Gladwell’s earlier work: In Outliers, Gladwell’s finally writing about ideas that, as he puts it, represent his “very bedrock beliefs.”

The other way Gladwell explains his success is more succinct: “People are experience rich and theory poor. My role has been to give people ways of organizing experience.” That’s only part of it, though. Gladwell’s real innovation is providing theories that organize experience in a deeply reassuring way. Gladwell isn’t just selling theories; he’s selling peace of mind. Much of this is achieved through skillful storytelling. Gladwell’s theories come packaged in nifty little tales, like Paul Revere’s midnight ride (Revere, you see, was both a maven and a connector) or the thin-slicing psychologist who, after a mere fifteen minutes of observation, can predict with 90 percent accuracy whether a pair of newlyweds will still be married in fifteen years. As an admiring reviewer in Time once put it, Gladwell is “like an omniscient, many-armed Hindu god of anecdotes.”

But the ultimate secret of Gladwell’s success is that his stories almost invariably have happy endings. As he readily admits, he is “congenitally incapable of glooming and dooming.” Even his account of Amadou Diallo’s shooting at the hands of four New York City police officers, which occupies a chapter of Blink, delivers the reassuring message that the cops weren’t racists acting with evil intent but, rather, simply poor mind readers who misunderstood Diallo’s actions. Thus, the way to prevent future police shootings, according to Gladwell, is not to undertake the impossible task of purifying people’s hearts but simply to train cops to “extract an enormous amount of meaningful information from the very thinnest slice of experience.”

Ever the optimist, Gladwell’s theories assume the good intentions of everyone involved. Today, as he watches the world’s financial systems collapse and people’s life savings go kaput, he radiates calm. Rather than joining the mobs seeking to hang villainous CEOs from the nearest lamppost, Gladwell counsels his followers to step back, take a deep breath, and find the procedural flaw in the system that can be fixed. “I don’t think anybody was being venal or corrupt. It’s not a scandal as we normally understand scandals,” he says. “It’s a case of the system being, the risk models being broken, the system not functioning as it should, regulation not being appropriate to what people were doing.” Tinker with the risk models, increase the regulatory structure, Gladwell says, and the problem is solved. That may not be as emotionally satisfying as punching out a CEO on a treadmill, but it’s a lot more comforting.

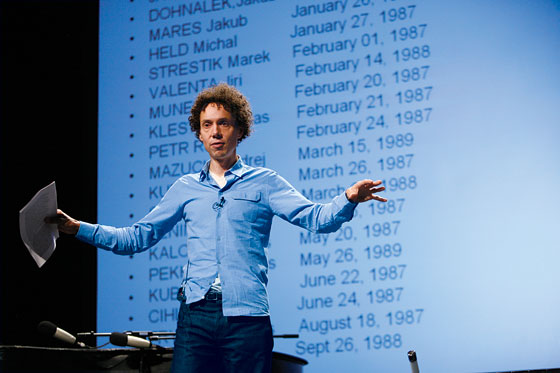

On a late October morning, Gladwell is standing on the stage of a nineteenth-century opera house in the ritzy village of Camden, Maine. He’s there to deliver some knowledge to the 600 or so “thought leaders”—primarily corporate and venture-capital types with a smattering of artists and activists—who paid $3,500 a head to hear Gladwell and other gurus like Chris Anderson and George Lakoff hold forth on the topic of scarcity and abundance at a Pop!Tech conference. As Gladwell paces the stage in a button-down shirt haphazardly tucked into some jeans and makes a few PowerPoint jokes that have his audience tittering, he’s clearly in his element.

For a guy who’s invariably described by his friends as shy, it’s striking how much Gladwell loves to perform. As a teenager, Gladwell was renowned for his skits; as an adult, he’s frequently tapped to give toasts at his friends’ weddings—toasts that, with their music and dance numbers, sometimes resemble community-theater productions. With his public speaking, he’s found a way to monetize these skills. Gladwell first went on the speaking circuit when he was working to promote Tipping Point. “He spent a year giving speeches before someone said, you know, you can get paid for this,” recalls Headlam. Now Gladwell does about 30 speeches a year—most for tens of thousands of dollars, some for free. He says he honestly doesn’t know what he makes from this lucrative second career. “I never deal with any of the money-negotiation part … It just goes into my account, so it’s like I’m not even aware.”

In fact, the entire topic of his money, which is a topic of great fascination to his admirers and detractors—the Atlantic Monthly writer Jeffrey Goldberg, who was introduced to his future wife by Gladwell, quips, “I have two thoughts: one, great for Malcolm, and two, since he is indirectly responsible for the existence of my three children, he really needs to give a little back to the community”—is one he does his best to ignore. “I have a financial adviser whom I told early, early on that I was uninterested in taking any risks,” he says. “I wasn’t interested in the upside, and I wasn’t interested in the downside, and she should act accordingly. I’m sure it’s under a mattress somewhere. If you want to make intelligent decisions or take chances with your money, you have to be interested in it. I’m just not.”

As for his talk at Pop!Tech, for which he was not paid, Gladwell seems to view the occasion more as an opportunity to preach than to entertain. When he addressed the same conference a few years ago, he talked about the differences between Coke and Pepsi, which he now concedes “may have been the most frivolous presentation ever in the history of Pop!Tech.” This time, he’s talking about a very serious academic concept, devised by the psychologist James Flynn (“One of my heroes,” Gladwell says, swooning), called the human capitalization rate, or “cap rate,” which, Gladwell explains, “refers to the rate at which a given community capitalizes on the human potential of those in its midst.” In the United States, Gladwell is sad to report, “cap rates are really low” owing to poverty, stupidity, and culture. He tells the story of an inner-city neighborhood in Los Angeles where the boys must cross gang lines to go to high school, so none of them go to high school. “We have a cap rate for that community in Los Angeles, one of the richest cities in the world, that is zero,” Gladwell says, disgust creeping into his normally tranquil voice, “because if you don’t go to high school, you basically can’t achieve anything in our particular society.” For about eighteen minutes, Gladwell goes on in this vein, thoroughly depressing an audience that was already feeling pretty glum after the stock market had taken another nosedive.

But then, with a light flashing yellow to let him know his allotted twenty minutes are almost up, he suddenly pivots. It’s time to let the gloom and doom give way to some Gladwellian optimism. “We have a scarcity of achievement in this country, not because we have a scarcity of talent,” Gladwell says, his voice taking on an urgent tone. “We have a scarcity of achievement because we’re squandering that talent. And that’s not bad news, that’s good news, because it says this scarcity is not something we have to live with. It’s something we can do something about.” Gladwell’s new idea may not be profound, it may not even be big, but it’s certainly welcome.

Why Success Is More Circumstantial Than Personal

In Outliers, Malcolm Gladwell posits alternative theories for how successful people got to where they are.

Bill Gates

As a kid growing up in Seattle in the late sixties and seventies, Gates had extensive access to a state-of-the-art computer lab, the likes of which very few in his generation would know anything about until years later.

The Beatles

In the early years, when they took up residency in the clubs of Hamburg, Germany, they had to play very long sets, in a wide variety of styles, forcing them to be creative and excel at experimenting.

Chinese Students

They work much harder at their studies and exhibit greater patience in problem-solving than their American counterparts thanks to their cultural legacy of long days toiling in rice paddies.

Youth Hockey Players

Kids born in the early months of a year are put in the same league as kids born later in the year, a slight edge in physical maturity that gets compounded over the years into a decisive advantage in skill.