Samuel R. Delany’s Dhalgren is—like Moby-Dick, Naked Lunch, or “Chocolate Rain”—an essential monument both to, and of, American craziness. It doesn’t just document our craziness, it documents our craziness crazily: 800 epic pages of gorgeous, profound, clumsy, rambling, violent, randy, visionary, goofy, postapocalyptic sci-fi prose poetry. The book is set in Bellona, a middle-American city struggling in the aftermath of an unspecified cataclysm. Phones and TVs are out; electricity is spotty; money is obsolete. Riots and fires have cut the population down to a thousand. Gangsters roam the streets hidden inside menacing holograms of dragons and griffins and giant praying mantises. The paper arrives every morning bearing arbitrary dates: 1837, 1984, 2022. Buildings burn, then repair themselves, then burn again. The smoke clears, occasionally, to reveal celestial impossibilities: two moons, a giant swollen sun. To top it off, this craziness trickles down to us through the consciousness of a character who is, himself, very likely crazy: a disoriented outsider who arrives in Bellona with no memory of his name, wearing only one sandal, and who proceeds to spend most of his time either having graphic sex with fellow refugees or writing inscrutable poems in a notebook—a notebook that also happens to contain actual passages of Dhalgren itself. The book forms a Finnegans Wake–style loop—its opening and closing sentences feed into one another—so the whole thing just keeps going and going forever. It’s like Gertrude Stein: Beyond Thunderdome. It seems to have been written by an insane person in a tantric blurt of automatic writing.

When I mention this to Delany, he is pleased. It is, he says, exactly the effect he was going for. And yet, he tells me, the actual writing process was deliberate and precise. “I wrote out hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of sentences at the top of notebook pages,” he remembers. “Then I would work my way down the page, revising the sentence, again and again. When I got to the bottom I’d copy the sentence out to see if I wanted it. Then I’d put them back together again. It was a very long, slow process.” It took him five years—not long by epic-novel standards, but a lifetime for an author who once wrote a book in eleven days to fund a trip to Europe.

In the 35 years since its publication, Dhalgren has been adored and reviled with roughly equal vigor. It has been cited as the downfall of science fiction (Philip K. Dick once called it “the worst trash I’ve ever read”), turned into a rock opera, dropped by its publisher, and reissued by others. These days, it seems to have settled into the groove of a cult classic. In a foreword in the current edition, William Gibson describes the book as “a literary singularity” and Delany as “the most remarkable prose stylist to have emerged from the culture of American science fiction.” Jonathan Lethem called it “the secret masterpiece, the city-book-labyrinth that has swallowed astonished readers alive.”

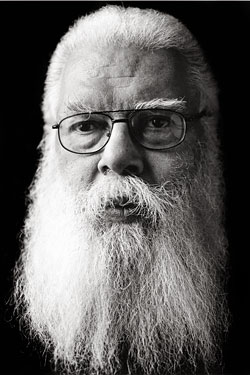

Delany, meanwhile, with his restless mind and his giant white cyberpunk-Santa beard, has become a science-fiction icon—a grandfatherly figure without any visible grandfatherly tendencies. He first emerged as a prodigy in the sixties, one of a loose band of young writers sometimes referred to as sci-fi’s “new wave,” whose work helped to push the tradition away from robots and spaceships toward deep questions about race, sexuality, and identity. His characters had explicit sex but also gave each other lectures on metalogic. By his mid-twenties, Delany had written a career’s worth of novels and won a career’s worth of major awards. He managed to fuse, unapologetically, qualities that few had ever thought to combine: He was pulpy, literary, lusty, academic, prolific, and meticulous. He was also, in a genre dominated by white guys writing heteronormative fantasies, African-American and openly gay. “From 1968 on,” he once told an interviewer, “I was pretty much the black gay SF writer.” (He was also married, for years, to lesbian poet Marilyn Hacker; they have a daughter.) Delany is a living refutation of the fixity of genre and identity boundaries. He has written memoir, film, historical fiction, pornography, theater, Wonder Woman comics, literary theory, and urban history—his Times Square Red, Times Square Blue is a classic account of what New York lost when it turned midtown into a shopping mall.

Among all of Delany’s many projects, Dhalgren is still his best known. At its core, it’s a meditation on the nature of cities: how they live and die, cohere and fracture, nurture and consume their citizens. Delany grew up in Harlem, where his father was a successful undertaker. He started writing Dhalgren in the East Village and finished it in London, stopping along the way in a smorgasbord of major and minor cities: New Orleans, Toronto, Seattle, Vancouver, East Lansing, and Middletown, among others. The result is a stew of different urban vibes. Not long after Dhalgren was published, someone wrote Delany a letter saying it seemed to have drawn its exteriors from New York and its interiors from San Francisco. “I thought that was a remarkably astute observation,” he says. “This was a woman who lived in Indianapolis.”

It seems appropriate that Dhalgren, or at least the latest mutation of it, will return this month to the city of its birth. On April 1—Delany’s 68th birthday—the Kitchen will begin staging an adaptation called Bellona, Destroyer of Cities. Its director and writer is Jay Scheib, an MIT professor and rising theater-world star who’s been obsessed with Dhalgren for years. He once devoted an MIT course to the book, and has even adapted it into a play in German.

“It took me roughly a year to read Dhalgren for the first time,” Scheib says. “I would read the same ten pages over and over and over again.” The loop structure impelled him to keep coming back. “You get the feeling that the story has been going on like a fugue for millennia,” he says. “The second time you read it, it’s thrilling. The third time, it makes you high. After that it’s like reading philosophy.” The play’s producer, Tanya Selvaratnam, took the opposite approach, reading the entire book in a day and a half; by the end, she says, she felt like she was hallucinating. One of the actors told Scheib that reading the novel was the hardest thing he did all year. (Delany hasn’t read the book in probably fifteen years and has little interest in doing so; his energy is focused on “futzing” with his next novel, Through the Valley of the Nest of Spiders, due in November.)

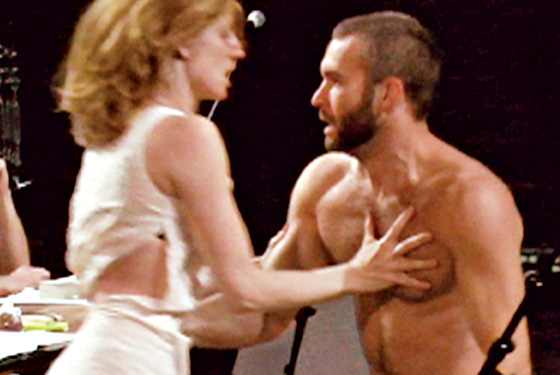

The notion of turning Dhalgren—this disorienting vortex of pure textuality—into a functional play seems, at first, like some kind of literary joke, the equivalent of turning the Tao Te Ching into a murder mystery. Scheib concedes that the task occasionally feels impossible. For the Kitchen show, however, he’s come up with a handful of innovative solutions. He describes the set as “buildings and rooms inside of buildings and rooms,” portions of which will be hidden from parts of the audience. Live cameras will provide glimpses into areas that can’t be seen directly, mimicking the novel’s shifting perspectives and layers of mediation. The way the actors move is designed to evoke Dhalgren’s strange prose rhythms. “We’ve tried to find a physically charged syntax that would stand up to the images and actions of the novel,” Scheib says. “We move through dance and extreme physical actions. Things that aspire to be a kind of poetry in space.”

The surprising thing is that it all seems to be working. When I sit in on a rehearsal, the feel of the novel is unmistakably present: the openness, the casual strangeness, the charmingly aggressive discomfort. Delany, who also sat in on a read-through, agrees. “All too often,” he says, “when creative people pick out someone else’s creative work as an inspiration, what they end up with is very, very far from the original. I was prepared for that. But this felt familiar to me.”

The Kitchen adaptation aims to be the next cycle of Dhalgren: It begins where the novel ends, with a new character—a woman instead of a man—entering Bellona. “In the novel,” Scheib says, “when the narrator shows up, he has sex with a woman who turns into a tree. And then he has sex with a guy, and then with a girl. Then another guy. Then a guy and a girl. So we try to keep that spirit alive.” Scheib points out that, 35 years later, Dhalgren remains improbably contemporary. “We still battle with race and identity and sexuality,” he says. “In the world of Bellona, people seem to have made peace with a lot of that stuff. There’s a different attitude: They talk openly about their problems and wear their prejudices on their sleeve, and it’s somehow okay. Difference produces meaning in a way that it doesn’t sometimes in life.” Which is almost as bizarre, in its way, as a pair of moons in the sky.

DhalgrenBy Samuel R. Delany.

Vintage books.

$18.95.

Bellona, Destroyer of Cities

The Kitchen.

April 1–10.