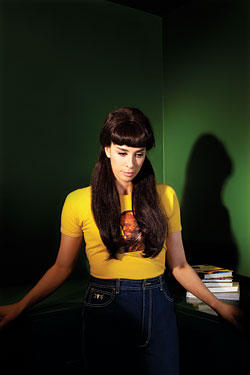

Sarah Silverman lives in a very small apartment—possibly the smallest of anyone who has ever had her name in the title of a TV show. Her compact one-bedroom is halfway up a high-rise building in West Hollywood. The living room has a dandy view of the Sunset Strip, a big TV, and a couch. That’s it. Her bathroom has wires hanging from the ceiling. Décor consists of family photos taped to the wall. There are tiny dog hairs everywhere. (Her elderly Chihuahua, Duck, plays himself on Comedy Central’s The Sarah Silverman Program.) “I almost own the apartment,” she says cheerfully. “I have no plans to move. This is perfect for me. I own my Saab. I don’t have big dreams of anything or want for anything. Money to me has never been a reason to compromise. You’re very free if you don’t love money.”

Silverman gets compared a lot to Lenny Bruce because she talks dirty and makes jokes that are provocative, or offensive, depending on whether you find her funny or not. But in her new book, The Bedwetter: Stories of Courage, Redemption, and Pee, she writes that her greatest influence was not Bruce but Garry Shandling, who cast her on The Larry Sanders Show when she was 27. And she is more like Shandling—absurdist rather than confrontational, and only accidentally political. She also shares an interest in meta-comedy, creating a persona version of herself. It’s the reason she now refuses roles that she can’t control, like the one she played in the film School of Rock—what she calls the “Suze”: a female whose only purpose is to serve as the straight man to her male counterpart. She’s happiest working on The Sarah Silverman Program, where she always gets her way, for better or, debatably, worse. In a recent episode, a supporting character attempts to exact revenge on a pigeon by excreting on it. “The writer’s room is just so animalistic,” says Silverman. “It’s like there’s this safe haven with only six of us being animals, and I get joy from it. It’s absolute, total freedom.”

I mention to Silverman that, anecdotally, I find her fans to be mostly male. (That she’s a vocal pothead might be one reason; she proudly points out to me that her book’s release date, April 20, is Stoner Day.) She tells me that she has zero interest in a conversation that might turn into a Woman in a Man’s World discussion. “A lot of women comics got all upset by Christopher Hitchens’s [Vanity Fair, January 2007] article about why women aren’t funny. Or like when Jerry Lewis says women aren’t funny,” she says. “If you are truly offended by an 80-year-old man saying you’re not funny, then you’re probably not funny.”

She doesn’t say this with any attitude. Silverman is unfailingly sweet in person—like her stand-up act, minus the off-color jokes. The only time she slips into character is when I say, in an awkwardly phrased reference to recent backlash, “There’s been a concentration of attention on you.” “A concentration camp,” she responds, almost Tourettically.

I ask her how she thinks people perceive her and she explains her Vanna Theory. “Vanna White became a huge star because no one knew anything about her, other than that she was the pretty lady who turned letters. People took everything they wanted her to be and put it on her.” In Silverman’s case, the pretty lady is dressed like a little girl, with pigtails, or in an adolescent getup of jeans and a T-shirt. From the mouth of this construct come jokes like “I saw my father’s penis once. But it was okay because I was so young … and so drunk.” Or: “I don’t care if you think I’m a racist. I just want you to think I’m thin.” Audiences see Sarah Silverman and assume she’s a nice Jewish girl, but oy! The trash she talks! She is the joke. The confusion over whether she’s exploiting stereotypes or puncturing them is what gets her into trouble.

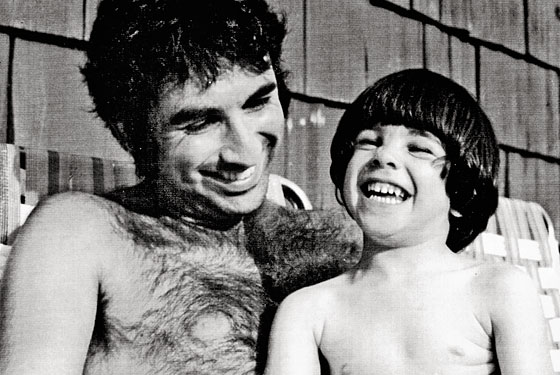

Silverman grew up in Bedford, New Hampshire, a state with the oddly appropriate motto Live Free or Die. Her father owned a discount-clothing store and her mother raised four girls (her parents are now divorced). Sarah, the youngest, seems to have sprung from the womb doing shtick. According to The Bedwetter, as early as the age of 2 she was making her affable father laugh by saying “fuck.” No one was ever offended by Silverman’s provocative humor, says eldest sister Susan, now a rabbi in Israel. “Sarah was always, and is still, adorable and adored.” Her sister Laura, who co-stars on The Sarah Silverman Program, says, “She always had this beautiful quality of seeing what she has and not brooding over what she doesn’t.”

The Bedwetter reveals a tenderness that is disarming; the first quarter is essentially a love letter to her sisters and parents. (In an unusual tribute to her mother, Silverman has papered the wall of a storage closet with a blown-up photo of her, partially visible on the previous page.) The book is not a Mackenzie Phillips–style tell-all, but Silverman had her share of anxiety (this is, after all, a story about comedy): a high-school depression so intense she dropped out of school for a year and took sixteen Xanax a day; the titular bed-wetting, which lasted until she was 16; and the death of a stillborn brother, which taught her that there are some things you absolutely cannot joke about with your parents. But while it can be revealing, it is curiously unreflective, much like Silverman’s stand-up. When I ask her about the absurd amounts of Xanax she was popping, she says, “It was a time when you didn’t question doctors.” She stonewalls further attempts to dig into her psyche, offering only that “everyone has sad stories.”

So why write the book? It wasn’t Silverman’s idea to do it, but once she agreed she didn’t want it to be a typical comedian’s riff on events, like Dennis Miller’s Rants. The odd, shambling, and funny result is as close to an explanation of Silverman and her comedy as we’re likely to get. It seems to be saying, Obviously I’m joking, but it’s also me up there.

At 39, Silverman has already spent over half her life performing professionally. She began doing stand-up after she dropped out of NYU at 19. She passed out comedy-club fliers for $10 an hour from 4 p.m. to 2 a.m., sharing the corner of West 3rd Street and Macdougal with a drug dealer named Sandy. At 22, she wrote for Saturday Night Live. At 26, she was on Seinfeld, followed a year later by the gig on Larry Sanders. Her breakout moment, she says, was her infamous 2001 appearance on Late Night With Conan O’Brien, when she made a joke about avoiding jury duty by writing “I love Chinks” on her questionnaire. Afterward, Guy Aoki, head of the Media Action Network for Asian-Americans, blasted her for the racial slur, then debated her on an episode of Politically Incorrect With Bill Maher. Silverman devotes a short chapter to the episode: “Guy Aoki: Heart in Right Place, Head Up Wrong Place.” In it she points out that men with jobs like Aoki’s “require a more nuanced perception of irony and context … not only are the progressive messages out there more refined and sense-of-irony dependent, but racist messages are more oblique too.”

“Money has never been a reason to compromise. You’re very free if you don’t love money.”

The publicity resulting from the dustup pushed Silverman from a slightly ribald comic to a First Amendment social satirist, a role she initially embraced (once telling The Believer that she likes “saying things that force people to have opinions”) but now finds oppressive. For Silverman, unlike Lenny Bruce, does not thrive on confrontation. In her new book, she relays a crack she made about Paris Hilton while hosting the 2007 MTV Movie Awards. Hilton was in the audience, with jail time imminent, and Silverman joked that to make her more comfortable, the bars on the cell would be painted like penises: “I just worry that she’s gonna break her teeth on those things.” Hilton was upset enough that Silverman wrote her a note of apology. “She was out there, probably terrified about going to jail, and everyone is laughing,” Silverman says now. “I never want to make a girl feel bad.”

Silverman’s reaction surprises people. That she is taken aback by her comedy’s effects is naïve but not ridiculous. Thanks to her 2008 viral hit, “I’m Fucking Matt Damon,” she moved quickly from being a comic’s comic, living primarily in a comedy-world bubble with a rabid cult following, to a mainstream entertainer. And being a player in this wider universe of popular culture has made her uncomfortable. Not everyone gets that her humor is essentially victimless; critics find her comedy disrespectful, juvenile, even mean. “Matt Damon” was directed at Silverman’s then-boyfriend Jimmy Kimmel (he responded with “I’m Fucking Ben Affleck”). The two were comedy’s high-profile golden couple until they broke up in March 2009, but he remains a big fan and defender. “The world of comedy is composed primarily of angry, envious people,” he says. “Sarah is one of few who genuinely roots for her colleagues and takes pleasure in their success. I’ve never heard her say a mean thing to anyone, in public or privately. Cruelty is never her intent.”

Chris Anderson thought otherwise. The curator of the TED (Technology, Entertainment, Design) Conference asked Silverman to speak at the annual event this past February. She was a logical choice. Her “The Great Schlep” video, asking Jews to fly to Florida to encourage their grandparents to vote for Obama, was a viral smash (Frank Rich jokingly credited her with handing Obama his victory). And though Anderson didn’t know it at the time, she’s a longtime TED fan. (“My mom and I used to send each other TED videos all the time,” says Silverman.) Still, she wondered if Anderson was familiar with her comedy. They had a conversation beforehand and she told him her onstage character was “sort of an Archie Bunker–Meathead thing.” Silverman got the sense Anderson didn’t like her. “I’m not into vibes, but it was a bad vibe.”

Still, she agreed to appear, and “I swear to God, I killed. I got a standing ovation.” She flew to Burbank directly afterward for a Haiti fund-raiser, and by morning, all hell had broken loose. Anderson started the next day’s conference by apologizing for Silverman, then tweeting, “I know I shouldn’t say this about my own speakers, but I thought Sarah Silverman was god-awful.” When she heard about it, she was stunned, responding with her own Twitter, “Kudos to @TEDChris for making TED an unsafe haven for all! You’re a barnacle of mediocrity on Bill Gates’s asshole.” Out of nowhere, AOL co-founder Steve Case sent Silverman an anti-tweet of his own: “Shame on you.”

If you want to watch Silverman’s TED routine, you can’t: It was never put online. So she tells me the joke. “The bit was tied into the theme of the conference, which was ‘What the World Needs Now.’ So I say I’d like to adopt a retarded baby because I don’t have this urge to have a little version of myself to get right this time.” She stops to explain her feelings about the word retard. “I don’t like it. I think it’s a negative bummer word. Retarded, however, technically means [mentally challenged].” She continues: “So I say I’m adopting a retarded baby and I’ll be worried about who will take care of my child when I’m gone. So, solution! I’m going to adopt one with a terminal illness. Now, you’re probably thinking, what kind of person looks to adopt a terminally ill retarded child? An amazing person! I don’t see those 9/11 firefighters adopting retarded children with terminal illnesses. I’m just saying. Of course, there’s going to be the uncomfortable, inevitable question in the adoption process: Are you sure there are absolutely no cures on the horizon?”

Funny or not, this is exactly the bit a Silverman fan would expect her to do at a TED conference devoted to “What the World Needs Now”: It’s theoretically offensive, it’s a new twist on a current issue (notably, what the word retarded really means), and it sends up liberal piety at a conference devoted to that very thing. As Times critic A. O. Scott once wrote in a review of her 2005 concert film, Sarah Silverman: Jesus Is Magic, “Her version of insult humor is actually flattering, both to herself and to those who find it funny … everything she says is delivered through enough layers of self-consciousness—air quotes wrapped in air quotes—to make anyone who finds it offensive look like a sucker.”

Silverman wanted to include Scott’s entire review in her book but ultimately it was cut for space. “I got what he said, and I thought it was cool,” she says. Her reaction to the review reveals her openness to analysis and criticism. Which doesn’t mean, however, she isn’t deeply hurt when her comedy is taken the wrong way. “What a bummer,” she says of the TED situation. “I came with my heart so open and so excited to be a part of this thing. I know I’m a grown woman, but it felt like these two grown-ups [were] attacking me. I had a benefit for Down syndrome that was booked before TED, and they got so nervous after that. ‘We want to make sure you won’t use the R-word.’ They were being so kind, and it was just so heartbreaking.”

In a clever conceit, The Bedwetter’s afterword is written in the voice of God, on the occasion of Silverman’s death in 2063 at age 93. He recaps her career (in 2018, she’s banned from show biz for being too old to be “cute”) and delivers an epitaph: “She loved dogs, New York, television, children, friendship, sex, laughing, heartbreaking songs, marijuana, farts, and cuddling.” The epitaph is premature, the recap less so. In December, Silverman will turn 40. She’s aware of the implications without being paralyzed by it. “I can’t be in my forties with pigtails and a football shirt,” she says. “It turns into something different then.” But she does recognize the need to evolve. She’s working on new stand-up material but finding it difficult. “My old stuff is old and done,” she says. “I’m starting over with people knowing who I am, so it’s an odd place.” Silverman claims to have no master career plan, but the “animalistic” joys of her TV show’s writers’ room are clearly more appealing to her right now than the controversy that has come with mainstream popularity. Curiously, she brings up Andrew Dice Clay a couple of times. Turns out her biggest fear is that her comedy will get stuck in a similar rut. “The road is how most comics make their living. There’s that quandary of stand-up,” she says. “The audience wants to see the Diceman. When the Diceman continues to be the Diceman twenty years later, he’s a caricature. He’s giving the audience what they’re paying for. I don’t want to be the comic who talks about race all the time. So I’m moving on to poop and pee.”