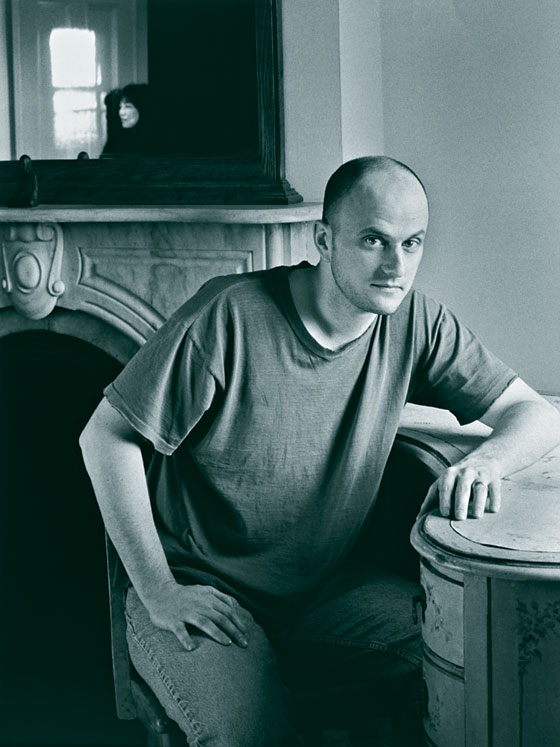

When Jeffrey Eugenides moved to New York, he was 28 years old and things were not looking good. After graduating from Brown in 1983, he and Rick Moody, a college friend, had driven out to San Francisco with no real plan other than making a go of it as writers, and lived together awhile on Haight Street, listening to the sound of the electric typewriter coming from the other room. Eugenides stayed in the city for five years and didn’t publish a thing. He calls these “the lost years” now. “My life just didn’t seem to go forward.” In 1988, Eugenides moved into a cheap place with roommates on St. Johns Place in pre-gentrified Prospect Heights, Brooklyn, when muggers freely worked the area. A $75 payout on a scratch-off lotto card was a bright spot of that summer. Eugenides would look out over the darkening rooftops at the Manhattan skyline and think, How can my writing take me from here to there?

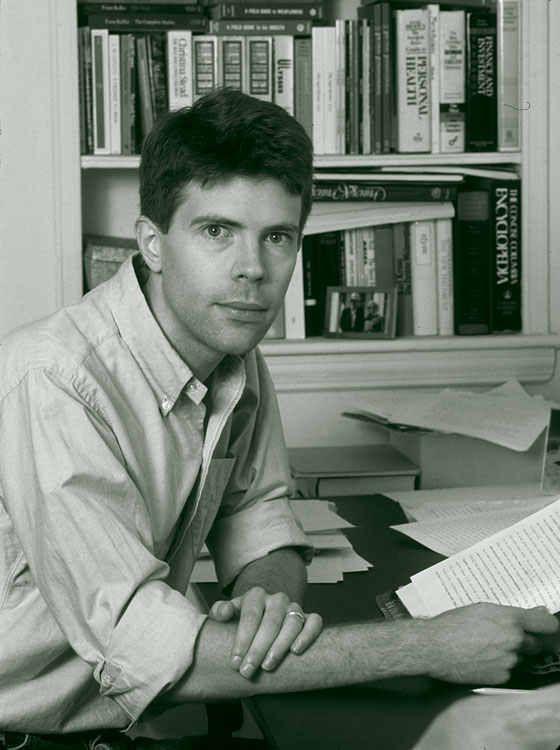

That same summer, Jonathan Franzen, also 28, was living in Jackson Heights, Queens, and feeling “totally, totally isolated.” The neighborhood was an immigrant jumble, and Franzen was a solemn, intellectual guy from St. Louis without much occasion to leave the house. He had gotten some attention and money for his debut novel, The Twenty-Seventh City, but the axis of the planet had not obediently shifted. He was frustrated with living in “shared monastic seclusion” with his then-wife, he says, when he got a fan letter from a writer he knew of but had never read. David Foster Wallace, then 26, was having dire troubles of his own and wrote to praise what Franzen had done in a “freaking first novel.” It was the first time Franzen had ever heard from a peer, he says. “And I was desperate for friends.”

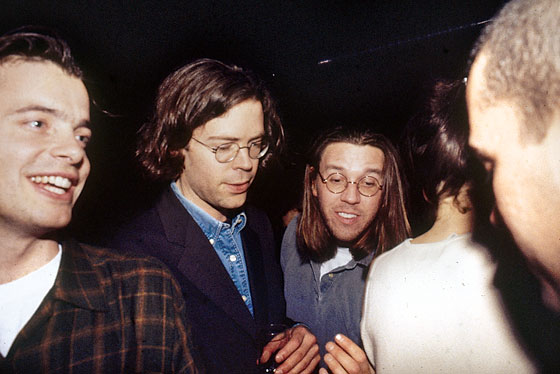

Gradually, he found some: first Wallace, then William T. Vollmann, David Means. Through Wallace, who also knew Vollmann, he met Mary Karr and Mark Costello. Later Franzen would connect with Eugenides, Moody, and their other college friend Donald Antrim. A scene was taking shape and growing. Some had published work when they met, but many hadn’t; some were closer than others, some more competitive. The crowd was overwhelmingly male, very close in age, largely from the Midwest, and engaged in a kind of generational struggle to make sense of the postmodern literary legacy—of Thomas Pynchon, John Barth, and others—that they found both consuming and unsatisfactory, especially as a guide to writing about the new, weird America of the eighties and nineties.

Those writers seem even more a distinct literary cohort now in the wake of Wallace’s suicide in 2008; Wallace was the youngest of the bunch and the one most openly at war with himself over the way forward for fiction, and his death seems to have galvanized them all. Karr, who had a stormy relationship with Wallace in the early nineties, wrote him into her memoir-in-progress, Lit, though she used only his first name. Franzen sat down and channeled his anger over his close friend’s death into a fourteen-month sprint to write his sprawling 2010 novel, Freedom, which features a character with a likeness to Wallace. He also published a raw and searching New Yorker essay on their complicated friendship. “The depressed person then killed himself, in a way calculated to inflict maximum pain on those he loved most, and we who loved him were left feeling angry and betrayed,” Franzen wrote. “Betrayed not merely by the failure of our investment of love but by the way in which his suicide took the person away from us and made him into a very public legend.”

And when readers open Eugenides’s long-awaited and absorbing new novel, The Marriage Plot, published this week, they’ll find a character who looks very much like Wallace—bandanna, chewing tobacco, expertise in philosophy, struggle with mental illness. Another character looks a lot like Eugenides—a Greek-American from Detroit engaged in religious studies at Brown who takes a big trip abroad and ends up volunteering for Mother Teresa in India. In the book, the two are rivals, and while Eugenides insists the resemblance to Wallace is unintentional, The Marriage Plot is unmistakably a portrait of the author’s youth and of the loyalties and rivalries that so often arise among ambitious young friends. (Much of the early chatter surrounding the novel has been a who’s-who inside-baseball guessing game.) At once a love story, a campus novel, and a bildungsroman, The Marriage Plot is stocked with literary references and choreographed to provide the great page-turning pleasures of realistic fiction—very knowingly. It’s the latest salvo, that is, in the debate that has occupied Eugenides’s generation for 25 years, about what exactly fiction is for and how a crew of literary newcomers might revive the American novel, which seemed to many of them in danger of irrelevance. The Marriage Plot invites us back to that era when the author and his contemporaries were just starting to rewire their aspirations. What makes the backstory so intriguing is who this crowd was and who they came to be.

“I remember when The Broom of the System came out,” Eugenides says, referring to Wallace’s debut, published in 1987. Wallace was 24, and Eugenides remembers that too. “Like everyone else, when you first read any of Wallace, all the way through to Infinite Jest, what you felt was that he’d caught the sound of the times and the sound of his generation like no one else had.”

That kind of praise had given Wallace some stature but little real comfort by 1989. He was living with his closest friend, Mark Costello, an Amherst roommate who would go on to write, among other novels, Big If, a National Book Award finalist. They had a dumpy apartment with milk-crate furniture in “a sagging clapboard triple-decker,” Costello says, in Somerville, Massachusetts, in a neighborhood with “opera from the windows, tough guys in the street, Madonnas on the lawns.” Wallace looked less like a literary talent and more like a guy who’d given up high-level tennis for the parking lot at 7-Eleven. He’d soured on his own fiction, which seemed to him empty, and enrolled in a Harvard graduate program in philosophy that began that fall. But the academy and its politics didn’t hold the answer either, and Wallace was drinking heavily to try to dull an increasingly severe depression.

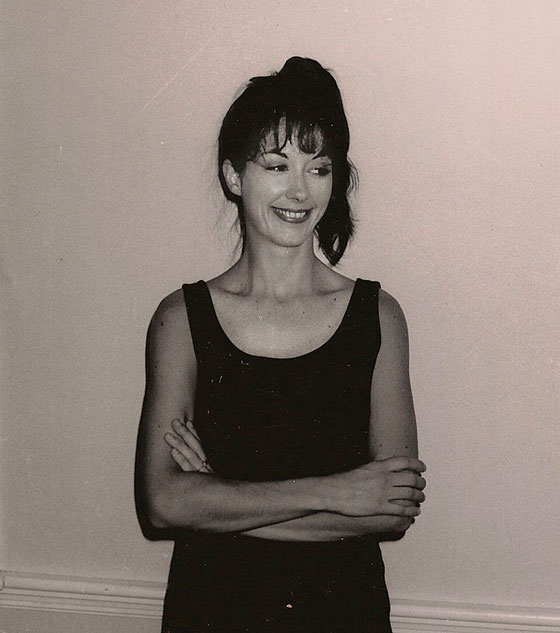

In November, Wallace told Harvard health authorities that he felt he was a threat to himself, and he was sent to a locked ward at McLean Hospital, the well-known psychiatric institution in Belmont, Massachusetts. The head of the Whiting Foundation heard the news and asked Mary Karr, who had recently won a Whiting Award for her poetry and was living nearby with her husband, if she would go see Wallace when he was in detox.

At first, she didn’t like him, she says; he was both pretentious and fawning. Just seven years older, she didn’t take to being called “Miss Karr.” She knew he was meant to be “some kind of genius,” but, she says, “I was over intellect.” Karr was not yet the author of her memoir The Liars’ Club, but she already had that voice, funny and bracing and blunt. Wallace was taken with her. Later that winter, he made Costello drive him the width of the city to “accidentally on purpose” catch a crowd leaving a basement meeting at a big stone church in Harvard Square. They stood in the snow, Costello recalls, and Wallace “pointed to a harried but beautiful woman in a sixties-type overcoat (knee-length, like Ethel Kennedy circa 1965) and said, ‘That’s Mary Karr.’ ”

Karr was battling to get sober herself. She and Wallace attended the same therapy groups, and she volunteered at the halfway house he lived in, Granada House. In Lit, she describes walking into the “shambling” building for the first time: “I expect to find tattooed thugs and strippers and former felons, which I do.” But there was a professor and an ex-lawyer too—a democracy of misery. Wallace was tutoring a former hooker trying to get her GED. Before romance became involved, he and Karr talked books. And Karr spoke her mind.

“I hated The Broom of the System,” Karr says. “I thought it was one of the worst books ever written.” She felt Wallace was “showing off,” writing fiction that pointed to all that he’d read rather than stirring feeling in the reader. And wasn’t that the point? If the literary bright white guys were going to follow in the line of the bright white guys of a generation before, she wasn’t interested.

Her tough talk didn’t dampen Wallace’s enthusiasm. The fact that she was “outside the amen circle of metafiction was interesting to him,” Costello says, and her lucid, personal prose captivated Wallace: Costello remembers Wallace later recounting, in detail, a traumatic episode in the childhood memoir Karr was just beginning to write. It was the kernel of The Liars’ Club, “the place where Mary found the famous voice of that book, part Flannery O’Connor and part Stop-Time.” Wallace heard her out when she tried to pry him from the clutches of the brainiacs who left her cold. That critique would echo.

“I was basically running the same line on him,” Franzen says. He thought Wallace was favoring the in-crowd at the expense of the broader audience, though some critics were saying the same of Franzen then. Their relationship was beginning to bear some resemblance to the competitive friendship at the center of Freedom, with Richard Katz in a Wallace-like role: “And the eternally tormenting question for Walter … was whether Richard was the little brother or the big brother, the fuckup or the hero, the beloved damaged friend or the dangerous rival.”

“In hindsight it was kind of a mean letter I wrote about Girl With Curious Hair,” Franzen says, referring to the Wallace story collection that got scant attention when it came out, three months before he was hospitalized. Franzen says he wrote Wallace that “ ‘there’s one story in here that has actual emotional content, as far as I can tell.’ And he said, ‘Oh my God, that’s the one story in that collection I hate.’ ” It was “a prickly correspondence,” Franzen says. “So much so that at one point he wrote, ‘You seem so mad at me. Why do you want to be my friend?’ ”

While Franzen and Wallace had books to show for themselves by their late twenties, Eugenides hadn’t even published a short story when he joined Moody and Antrim on the East Coast. Eugenides was starting to break free of the Brown campus fetish for literary theory (“Books aren’t about ‘real life,’ ” an in-the-know student says in The Marriage Plot, “books are about other books”), but he hadn’t figured out what would replace it. He got a job as an executive secretary at the Academy of American Poets, for $17,000 a year, and submitted a number of stories to James Linville at The Paris Review, a friend through his ex, trying out different styles—some light, others somber. No luck.

Eugenides says he’d always trusted Virginia Woolf’s advice not to publish a book before the age of 30, but now he was rounding that bend and he wasn’t close. “The shoe started pinching a bit,” he says. Antrim lived near Eugenides’s office, and the two would get lunch together to critique each other’s work. Moody was working as an editorial assistant at Farrar, Straus & Giroux, and he would meet up with Eugenides and bring him free books, including a debut novel he told Eugenides to read—The Twenty-Seventh City, by Jonathan Franzen.

Eugenides finally broke through with a piece of fiction in The Paris Review late in 1990. “It was like nothing else he’d done, like nothing else anyone had done,” says Linville. “It had that very unusual choral voice and was quietly insinuating.” It was the first chapter of what became The Virgin Suicides, a lyrical evocation of adolescent desire and the mystery of self-violence set in the Detroit suburbs of Eugenides’s youth—a sure step away from Brown but still a novel built from formal innovation. Pressing on with it in the ensuing years, Eugenides would write on the sly at work, typing out scenes on office letterhead below dummy first lines: “Dear John Ashbery.” He got fired for it. But that only helped him pick up the pace. The six months of unemployment checks were crucial.

“You seem somad at me,” Wallace told Franzen. “Why do you want to be my friend?”

Costello told me of Wallace’s reaction to the novel: “He liked The Virgin Suicides, and it ate him up.” He immediately made fun of the publicity photo and the typesetting (“too airy” to be serious), then started to “parody himself for doing so”—a typical Wallace switchback. He was “working himself into a small froth of self-loathing,” Costello says. “Jealous Dave was a dismal thing to be around, seeing those gifts put to that use. Of course, we’re all dismal when jealous. But Dave was brilliantly dismal.”

Franzen was feeling pretty dismal, too, corresponding with Wallace about “how irrelevant we were feeling to the culture” as novelists—a subject Franzen would later tackle in a much-discussed Harper’s essay that tried to crystallize the question hanging over all of them: Was fiction about mastering the sweep of the culture in an innovative way, or was it about telling a more intimate story and delivering reading pleasure?

Franzen had felt an immediate affinity when he first met Wallace in person: “I recognized an ambition in him and a talent in him that made me feel less alone.” But the notion of socializing with other authors gave Wallace some pause early on, according to Costello. “I think it’s important to remember,” he says, that “the idols of the generation were, in a sense, the allegedly monkish or hermetically sealed-off writers,” especially “Pynchon, who vanished.” Franzen had a different approach, Costello says. “I think Jon believed that ‘serious’ writers were basically an endangered, or at least threatened, species of warbler. Jon believed in forming common cause. It almost had the flavor of union organizing.”

“The key message that passed between them,” as Costello sees it, “was that every ambitious writer struggles.” He adds, “Failing to write wasn’t failure. Jon made it a credential. For Dave, who was naturally a solipsist and scalded by self-doubt, this was a salvific message as to which he needed hourly reassurance.”

Franzen needed a lot of reassurance himself after his second novel, Strong Motion, was published in January 1992 and got “just no response,” he says. Wallace kindly came to a Boston reading at a Waterstone’s in the teeth of winter. Some readings for the book were nearly empty, a “totally humiliating experience,” Franzen says, but this one “was worse than that.” He was sharing a stage with the Australian-born novelist Peter Carey, who had won the Booker Prize for Oscar and Lucinda. Franzen arrived in a college friend’s vintage Volvo in six-degree weather, with Wallace hitching a ride. “Carey arrived in a limousine from the Ritz.” The bookstore’s employees “had clearly never heard of me,” Franzen says. All of Carey’s books were on display, while a customer asking for Franzen’s previous novel was told to check the shelves under F.

Karr was teaching at Syracuse by this point, as she still does, and in Lit she describes Wallace’s coming there with “a pal” to scout out places to live in ’92. The pal was Franzen, who had taken a road trip up from Philadelphia with Wallace. They slept in Karr’s attic guest room in her house in the university ghetto. It was the last weekend of the NCAA basketball tournament, the year Christian Laettner hit the turnaround shot to beat Kentucky. Though his focus was clearly on Karr, Wallace was floating the idea that he and Franzen could both move to Syracuse. Franzen was open to it, but lost interest when it started snowing in April. They all went out for cheap Chinese and talked for hours, Karr writes, “till fortune-cookie slips confettied the linoleum booth top.” Karr’s marriage was on its last legs. They were three disheartened people.

Wallace did end up in Syracuse, in a small apartment very near Karr’s place. Karr had split with her husband, and Wallace came for her. Before they even kissed, Karr writes, he had her name tattooed on his arm. He proposed marriage and wrote her ardent letters from blocks away that barely fit in the envelopes. They rented videos like RoboCop from Blockbuster because they both “loved movies where shit blew up,” Karr says. “We laughed our asses off.”

But Wallace was volatile, Karr says, and she was sharp-tongued; their fights became frequent and virulent. Karr is a charismatic raconteur, and the portrait of Wallace that she painted in speaking with me was striking. In one fight, he threw her coffee table at her; in another, he stopped the car in a bad neighborhood and pushed her out, leaving her to walk home. Then he would try to win her back. He once climbed up on her balcony, she says, to “beat on the door like in the fucking Graduate.” This is not the familiar Wallace, wounded and ever sweet. Years later he wrote Karr a letter of apology, she says, for “being such a dick.”

While they were seeing each other, he also credited her for transforming him as he worked on Infinite Jest. He once wrote to her about the “long thing I want to do” and said that when he looked at material he’d written earlier, it wasn’t as “awful” as he feared, but it was “way too concerned with presenting itself as witty arty writing instead of effecting any kind of emotional communication with people. I feel like I have changed, learned so much about what good writing ought to be. Much of what I’ve learned I’ve learned from you, more from the example of your work and your feelings about your work than from any direct advice. You’re good about not giving advice; you just live, and let me watch.”

In April, the website The Awl published an article by Maria Bustillos about Wallace’s marginalia in self-help books held with his papers at the University of Texas’s Harry Ransom Center. Karr gave Wallace some of those books, and I told her that one of Wallace’s notes pertains to her—it uses her initials—and offered to read it to her. Karr has very good posture. At this moment it became even better.

Wallace remarks in the note that he seems better able to summon enthusiasm for something when it is secondary to something else in his life. He writes, “The key to ’92 is that MMK was most important; IJ was just a means to her end (as it were).”

“Who is IJ?” Karr said.

“Infinite Jest.”

“Oh!”

She did not seem flattered. I read the sentence again. “How is it a means—to capture me, is that it?” Karr said. “That’s crazy. That’s really insane.”

The writer Elizabeth Wurtzel got to know Franzen and Wallace in the mid-nineties. “Do you know how there’s some people that when it’s raining it doesn’t rain on them?” Wurtzel says. “On a sunny day it would be raining on Jon Franzen.” Wurtzel met Wallace at a reading in New York in 1995 when she was fresh from the phenomenal success of her memoir Prozac Nation, which rode a post-Nirvana wave. Wallace and Wurtzel struck up an intense extended flirtation, kicked off by a playful inscription in her copy of The Broom of the System (“Not my best thing,” he wrote) that complimented her candor and her nose stud. At the end of a letter to her about the conflict between altruism and commercialism in art, Wallace wrote, “PPS Call Jon Franzen and set him up with one of your comely friends—that would be altruism.”

In January of ’96, Franzen was due to give a joint reading with David Means as part of a series at the now-defunct Cafe Limbo. It had been four years since Franzen’s last novel was published, to poor sales, and he felt “utterly, utterly invisible.” “I’d been going through,” he says, pausing to sigh, “death of my father, collapse of my marriage, complete, yeah, just total—it had been a very bad year, a couple of years.” He was very thin at the time, with hair that hung below his ears.

Eugenides, Antrim, and Moody were all there at the Limbo, a colorfully decorated place with large windows giving out onto Avenue A. The crowd had spilled to the street the night Bret Easton Ellis read from American Psycho, and sometimes novels would sell on the basis of a reading there. Franzen had reason to be nervous.

“It was a terrific reading,” Eugenides says. “We didn’t know him very well then, and when he finished he came over and sat with us and said half-jokingly, ‘So, am I in the club?’ It’s very funny to remember that now. He read with tremendous authority, just as he reads now, but he was young, as we all were, and he wanted to be accepted. He wanted to be friends!” Franzen remembers that it meant a lot to him that the others told him, “You know, that was really good.”

Franzen’s initial encounter with Eugenides hadn’t gone so well: “The first meeting was a little bit awkward,” Eugenides says. “I had a girlfriend at the time, and I think he said she flirted with him.” But the two were soon getting together regularly for tennis in Central Park, where they laughed about Eugenides’s terrible serve—“the dying centurion,” they called it. While writing Middlesex, his Pulitzer-winning follow-up to The Virgin Suicides, Eugenides hit a sticking point and asked Franzen to read two chunks of about 150 pages each, representing two possible tacks for the novel. Franzen preferred the writing in one of them, Eugenides says, but in the end he went in another direction and was vindicated by the success of his multigenerational saga.

It was another novel-in-manuscript that had propelled Franzen toward his new phase—the thousand-plus pages of Infinite Jest. Almost all of what Franzen had read at the Limbo had been written in a kind of response to Wallace after getting an early look at his groundbreaking book. “I felt, Shit, this guy’s really done it.” As Franzen saw it, Wallace had managed to incorporate the kind of broad-canvas social critique that the great postmodernists did into a narrative “of deadly personal pertinence.” The pages Franzen produced then, he says, “came out of trying to feel good about myself as a writer after what an achievement Infinite Jest was.” His comments to Wallace weren’t all sunshine, though; he also “pointed toward some plot problems.” Wallace granted that the problems existed, Franzen told me, but said that he would thereafter deny ever having admitted it.

“I hated ‘The Broom of the System,’ ” Karr says. Wallace was“showing off.”

Nevertheless, Franzen knew it was “a giant book,” an end point of sorts. “It was clear that it was not going to be appropriate of me to try to compete at the level of rhetoric and the level of formal invention that he had achieved.” He turned instead to “a family story about a midwestern Christmas,” the beginning of which he read at the Limbo. The result was The Corrections.

That breakthrough novel provoked a six-page letter in ten-point type from Wallace. He wrote of his mix of happiness for his friend and his feelings of envy and depression. Franzen says, “I think it hurt for each of us to get the latest [book] from the other.” Franzen became more secure in himself in the wake of The Corrections, Costello says. But Wallace? “Dave never had a secure hour in his life.”

In 2006, Franzen was invited to a small literary festival called Le Conversazioni, on the Italian island of Capri. Reluctant, Franzen said he would come only if Wallace also signed on, “knowing that Dave would never do anything of the sort.” But Wallace, whose wife wanted to travel more, shocked him by agreeing.

If he had to go, Franzen decided, he might as well stack the deck with friends, so he brought aboard Eugenides. Between them, Eugenides, Franzen, and Wallace now had a Pulitzer Prize, a National Book Award, and a novel that launched a thousand fan sites and created a highbrow generational hero. The early years were over.

But even the victory lap of a glitzy festival gave Franzen little cheer: “That was a supposedly fun thing I will never do again.”

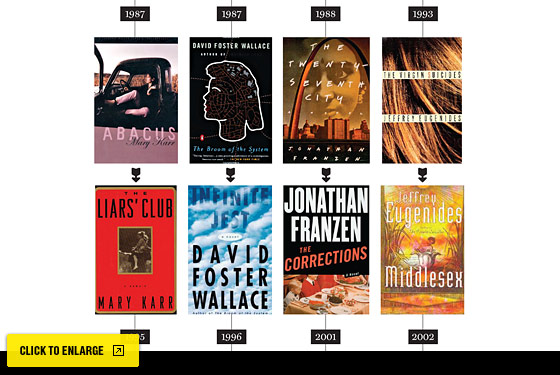

Generational Divide: Comparing the works of Eugenides’s generation.

“He didn’t like it because it was pleasurable,” Eugenides told me, adding that Franzen slipped away from the weeklong party for a while to go bird-watching. Meanwhile, Eugenides got to know Wallace, with whom he’d had a rapid-fire correspondence about religion after the publication of Infinite Jest. Like Eugenides, whose search for faith is a major element of The Marriage Plot, Wallace quietly sought out spiritual answers and flirted with joining the Catholic Church, as Karr later did. (When they were together, they tried to pray every day.) He told Eugenides those letters held a lot of meaning for him.

Wallace had a good time in Capri, much to Franzen’s surprise, at one point getting the crowd laughing with a riff about being “reduced really to the status of a baby” by trying to communicate without knowing any Italian. And later in the trip, Wallace went to Wimbledon for his essay on Roger Federer, which dropped sportswriting jaws everywhere. He seemed almost like a new man. Eugenides found Wallace more shy than expected but still lively and funny. They got along, as did their wives. “It seemed like the beginning of a friendship,” Eugenides says. He never saw Wallace again.