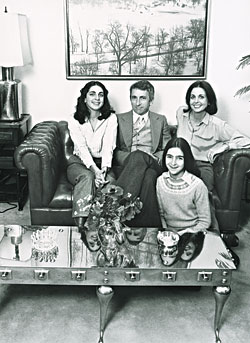

It isn’t until our third interview that I notice Gay Talese has been sitting underneath a painting of a naked woman with a rainbow coming out of her vagina. We are in the otherwise staid living room of his townhouse in the East Sixties, the home where he and his wife, Nan, the publisher of Nan A. Talese/Doubleday books, have lived for half a century. In fact, in June they will celebrate their 50th wedding anniversary, an impressive milestone for any couple, but perhaps few more so than this one. This legendary literary marriage—in all of its baroque complexity—has taken place entirely under this roof. It is here where they began their life together as a couple in their mid-twenties, when the five-story brownstone was like a tenement and Gay lived in 3F, a studio they both still refer to as his “bachelor pad”; this is where they raised their two daughters, Pamela and Catherine, and slowly took over every apartment in the building before finally buying it in 1973; this is where they have held innumerable book parties for Nan’s celebrated authors; and this is where Gay has done much of the writing—the historic Esquire pieces, the best sellers with biblical titles—that brought him fame, fortune, and no small amount of personal agony.

What’s absurd about the fact that I missed the rainbow vagina painting is that the subject of our conversation is, in so many words, sex. This month, Ecco re-published Thy Neighbor’s Wife, with a foreword by Katie Roiphe (along with a new edition of Honor Thy Father, foreword by Pete Hamill). The book, originally published in 1980, is about the sexual revolution, which Talese believed would be the most important cultural shift in decades, and which he spent most of the seventies intimately researching. It’s the research itself—particularly Talese’s tendency to take the participant-observer concept to the extreme—that turned out to be the unintended legacy of the project. “If you want to write about orgies,” says Talese, who at 77 is still slim and handsome, “you’re not going to be in the press box with your little press badge keeping your distance. You have to have a kind of affair with your sources. You have to hang out! I wanted to write about sexuality and the changing definition of morality. Maybe if I had put that in a subhead on the cover I might have gotten a better hearing.”

Instead, the book garnered him the worst reviews of his career (while also making him millions—the $2.5 million he was paid for film rights remained a record until 1991). Part of the reason critics were so appalled was because while Talese was gallivanting promiscuously and publicly, he was married, and not just to some anonymous wife but to Nan Talese, an important book editor at Random House whom many of the critics knew personally, professionally, or socially. Gay writes in his new afterword that in the immediate aftermath of the book’s publication, Nan accompanied him on talk shows “to explain that our marital love had remained unthreatened while I conducted research in New York massage parlors and a hedonistic nudist colony in Los Angeles”—which is only half true. As he has been telling me in exquisite detail, their marriage was pushed to the breaking point during this time. And so was his career.

Fair or not, it is a commonly held opinion in publishing circles that Talese’s career can be pretty much divided into pre– and post–Thy Neighbor’s Wife—that the writer and his gift never fully recovered from the shock waves. By 1980, he rarely wrote for magazines anymore, and it was a full twelve years before he published another book, Unto the Sons, which traced his Italian family’s immigrant history. Rumor had it that he was blocked, though Talese insists that wasn’t the case. He did, however, seek professional help. “One guy I saw for years was a Freudian,” says Talese. “The shrink was a very nice guy. He liked the book. But he said, ‘What you did was commit literary suicide.’ ”

It’s difficult to recover from such a leap into ignominy, and Talese has spent the decades since collecting material—photos, letters, anecdotes—about himself and Nan, as if looking for clues to his character’s motivations. In recent years, the collecting has grown more purposeful, and Talese has settled on an ambitious new project, the subject of which will take him right back to the scene of the crime, to the spot where everything went off the rails: a book about his marriage.

I ask him if the marriage book is an attempt to analyze what happened all those years ago.

“Yeah,” he says. “I have never dealt with it.”

Interviewing Talese is, among other things, an exercise in acquiescence. He seems to have a whole schedule mapped out for our conversations, every one of which begins with a stiff drink. As we finish our first cocktail, Talese suggests that the townhouse ought to be a character in the story and takes me on a tour, starting in “the bunker”—a plush cave under the streets of Manhattan where Talese writes.

There is no phone, no e-mail, no view, no sound. Along the walls there are shelves filled with brown file boxes that Talese has covered in collage. On one of the boxes labeled THY NEIGHBOR’S WIFE, he has taped a black-and-white photograph of the pinup Diane Webber lying on her stomach naked, legs spread just shy of beaver shot. Talese pulls one of the boxes down and begins to flip through the folders, all of them color-coded and fastidiously labeled. “This is the outline for the whole book on one page,” he says, handing me a piece of cardboard shirt-packaging. It’s a drawing, really, a bit like the rough sketch of a cartoon that a wordy artist like R. Crumb might conjure. Talese spends years reducing his research until at long last it all fits on a single piece of shirt board. And then he draws it. And then he starts writing.

On the other side of the room there are five boxes labeled MARRIAGE, one corresponding to every decade he and Nan have been together. Each of these boxes will eventually become a section of the book, which he plans to begin in 1980, the year Thy Neighbor’s Wife came out. The eighties box is open, and there are pictures spilling out. Talese has been going through every letter Nan ever wrote to him. “If it’s a letter of complaint, of which there are numerous letters of complaint, I write my own version of the incident,” he says. “I try to explain it, as if I’m trying to establish for a historian what this was all about.” There are also black spiral notebooks filled with transcripts of Nan being interviewed by reporters, whom Talese hired because he “wanted to read it like an outsider.” He picks up a photograph of his wife looking directly into the camera with big green eyes. “There’s Nan,” he says with a dark chuckle. “Smiling through the apocalypse.”

We head to the third floor so that Talese can show me his original apartment and suddenly there is Nan in the flesh. “Helleeeeew,” she says, in a voice that is part forties movie star, part English aristocrat, even though she is neither of those things. About ten years ago I became friendly with Catherine Talese and once had dinner at the family beach house in Ocean City, New Jersey. I have been quoting Nan quoting Hemingway ever since: “There’s nothing like a cracking cold Sancerre.”

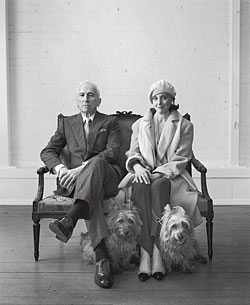

This part of the house is clearly Nan’s domain, with piles of manuscripts and galleys on every surface and two Australian terriers barking away, thrilled for some action. It seems far removed from Gay’s realm, just a floor above, where he keeps the artifacts of his storied career (including a life-size cardboard cutout of himself) along with his countless bespoke suits and dozens of hand-cobbled shoes.

“Was my first apartment 60 bucks a month?” Gay asks his wife.

“Fifty-twhooooo,” says Nan, as if she were playing a flute. A quizzical look crosses her face. “What are you two up to?” As it slowly dawns on me that Gay has not told her that he has agreed to participate in an article about their marriage, I can feel the tension begin to rise.

“Jonathan is going to call you,” says Gay.

“About what?” asks Nan.

“He’ll explain when he comes to see you alone.”

She turns to me and, laughing nervously, says, “You’re writing what?” About Gay, I say, but you too. “Oh!” she says, alarmed. There is an awkward quiet. Suddenly, Gay pipes up, a stern edge to his voice, giving an order. “So, he’ll see you alone, Nan.” Then to me: “Do you have her number?” Nan gives me the digits and then Gay says, “Good! This will be fun!”

A few days later, I’m sitting in Nan A. Talese’s corner office in the Random House building at 56th and Broadway, looking out at her spectacular view of the Hudson. “Isn’t it divine?” she says. At 75, Nan is elegant in slacks and kitten heels. After years of working her way up the ladder to editor-in-chief at Houghton Mifflin, she was given her own imprint at Random House in 1990. That was when she put the A (her maiden name is Ahearn) into her name, as if to say with a single letter: I am not just Gay’s wife. She is beloved by her authors—Pat Conroy, Margaret Atwood, Ian McEwan—who follow her wherever she goes.

When I first called Nan to schedule an interview, the small talk was brief and mostly about Gay. “He’s an eccentric,” she said, as if somehow that might nullify the agreement he made on her behalf. “Can we sort of be off-the-record? I just don’t want to be present on your page,” she said. Not at all? I asked. “My role is to be behind the curtains,” she said. But he’s writing a book about your marriage, I said. “Well then,” she concluded, “I have to obey my husband.”

Stuff of legend: One evening in 1972, when Nan and Gay were walking home from dinner at P.J. Clarke’s, Gay spied a neon sign above a building on Lexington Avenue near 59th Street that read LIVE NUDE MODELS. Gay said to Nan, “Let’s go check that out.” Nan said to Gay, “No, no, no. You go yourself. I’ll see you at home.” And right there, the seed for years of future discontent was planted: intrepid, rascally New Journalist from blue-collar Jersey tries to drag lovely post-deb wife from Rye, New York, into a dirty shame hole in their otherwise chic neighborhood. Several “massages” later, he had decided on the subject of his next book.

Before long, Talese was managing a massage parlor, the Middle Earth, at 51st and Third, just a block from the old Random House building where Nan worked. He got to know the masseuses, young women in their twenties, as they sat around between their appointments giving hand jobs to middle-aged men. The goal was to lie in wait until he found the perfect subjects: a man who could be a stand-in for himself, what Talese likes to call his “literary hostage,” and a girl half his age, someone who embodied the new un-hung-up morality, the free-love ideal that had so captured his imagination.

Word got out about Talese’s new day job, and one night in 1973, a writer from New York Magazine named Aaron Latham called to ask if he could hang around the massage parlor and write a story about how Talese does his research. Talese did him one better, taking the writer and his girlfriend to the Fifth Season, a nudist health spa, on West 57th Street. The resulting piece, “An Evening in the Nude With Gay Talese,” describes Talese running around the city with a bunch of louche swingers and living it up at sex clubs. The final scene has him heading off to an orgy at someone’s apartment.

“It was presented in a way that really trivialized what I was trying to do,” says Talese. “It didn’t take it with any seriousness; it was a mocking piece. It really put me down as a silly person. It was very diminishing.” You can still hear the self-laceration all these years later. “And Nan was very upset by that piece … It seemed that I was having one jolly good time and calling it research, as if it were an excuse to just go out there and get massaged by some great golden-fingered girl of the month.”

To be fair, it seemed that Gay had already been trying Nan’s patience with his research. He had even brought home a couple of potential subjects for dinner: a young woman who was a masseuse at the Middle Earth and one of her customers, a doctor, whom she was now dating. At dinner’s end, the doctor made a pass at Nan, and the night came to an abrupt close. Nan told Gay: “It’s your book, it’s your style of research. From now on, leave me out of it.”

A few weeks later, while Latham was still shadowing him, Talese found a note from Nan at the townhouse. “I opened it really quickly while Latham was taking his coat off,” he says. “Nan wrote, ‘I’m leaving.’ I put it in my pocket, and we went to Elaine’s.” Nan did leave him, but only for a few days. She returned without explanation or argument.

In Nan’s office, I ask about this whole dreadful episode, and her responses are remarkably measured. In some ways she sounds more like an editor talking about a writer than a wife talking about a husband. “I told Gay, ‘Don’t do it. You are not going to have your book out for a long time,’ ” she says of the Latham article. “I just felt that you don’t talk about a book until it’s written. I remember when the book came out, Gore Vidal said, ‘God, this must be volume three, we’ve been reading about this book for so long.’ ”

I press a little further: There are a lot of people who still believe that Gay humiliated you, I tell her. “No!” she says. “I think it was Eliot Fremont-Smith who wrote something with the headline ‘Can This Marriage Be Saved?’ There was just an assumption that I was suffering terribly and my husband had done this awful thing. But the fact is, he called me every single night from wherever he was. We never were apart for more than six weeks. And we used to meet for these romantic weekends in Chicago, which was sort of halfway [between New York and the nudist colony in L.A.], and stay at the Drake. And no matter how bizarre it all was, I never felt deserted or unloved by him.”

You’d think that, having weathered the storm of public scandal once, Nan might be reluctant to relive it, but she says she has no apprehension about the book’s rerelease. “I think it is a brilliant book,” she says. After he wrote the final chapter to address the controversy and his wife’s unhappiness—a section in which Talese switches to the third person—he asked her to read it. “I think he knew it would draw fire. And he said, ‘Do you think I should do it?’ And I said, ‘Yes.’ Because it seemed to me that I, his wife, was the rounding-out of the book … I mean, he got me to go to that [nudist] colony! He never lets you alone! Finally I said, ‘I now know why people talk to you. It’s easier to say yes because it gets you to go away.’ ”

In a way, the book he’s working on now is the perfect companion to Thy Neighbor’s Wife, sort of its opposite: Thine Own Wife. Talese says that the marriage book began to germinate when he was finishing Thy Neighbor’s Wife, but that he wasn’t ready to tackle it until a few years ago. When he first discussed the idea with his agent, Lynn Nesbit, she immediately called Nan: Do you know what he’s doing? Nan deadpanned, “I don’t think he knows anything about marriage, so it’s probably okay.”

“Her definition of marriage up against mine—they’re not what would be in the dictionary,” retorts Gay. “I’m not going to say I know everything, because I know there’s a lot about her that I don’t know. The private lives of people are an endless mystery.” Which is of course what’s so tantalizing about the notion of this book. Ever since Talese opened the door to their personal lives in the early seventies, he invited in all manner of speculation about the nature of their relationship. For years I have heard people describe their marriage as “open”—a term that implies that Nan, too, enjoys extramarital affairs. Nan has said in the past that she has not, though Gay, through coy hints in the press, would perhaps like us to believe otherwise. (“Nan has all these wonderful writers who are men. All those long publishing lunches. You never know where she is. This is not a woman living in a nunnery,” Gay said in an item in the Daily News last year.) Either way, their relationship fascinates people as much as it troubles them. Is Gay a philandering bastard or a pioneering anthropologist? Is Nan a doormat or a devoted wife with an unusually high tolerance for her eccentric husband’s sex research?

When I ask Gay if he is at all worried about dragging Nan and their relationship and even their sex life back into the spotlight, he says he’s not. “I think she’s a different woman than she was in 1980,” he says. “I don’t expect trouble with her this time, but I could be wrong.”

For what it’s worth, Nan has no intention of meddling. “You know, I just trust Gay,” she says. “When we married I made a little vow to myself that I would never interfere with his writing—whatever he wanted to write—and so far, I’ve been okay with that.”

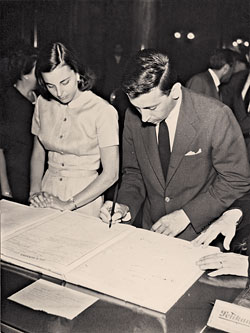

Nan and Gay were introduced through a friend in 1957 and “courted for two and a half years,” as Nan puts it. Her mother, a woman who had social ambitions for her daughter, was never crazy about Gay, but she insisted they get engaged if they were going to see each other exclusively. Nan faked their engagement by getting a formal announcement portrait taken, which “bought me another six months,” she says. But then the pressure was on to hurry the committed bachelor to the altar. When Gay went to Rome to write a piece for The New York Times Magazine and cabled her to join him, Nan saw her opportunity. First, she went to see her parents in Rye. “Gay has asked me to come to Rome to get married.” (She looks at me mischievously: “A lie! He hadn’t!”) Then she called Gay’s parents and asked them to send his birth certificate to the New York Times bureau in Rome and bought a one-way ticket on Alitalia.

When she arrived and told Gay what she’d done, he buried his head in his arm. “He said, ‘Aaaaaah! I’m too young to get married!’ He thought it was the worst idea in the world.” Gay can still work up a fresh outrage about what he calls the “Showdown in Rome,” but it’s coupled with a dose of admiration for Nan’s temerity. “She’s very courageous in a way,” he says. “She was this little post-deb, white-glove, Manhattanville, Sacred Heart girl, but she’s got her priorities in order.” And she played her cards well. “What were my choices?” asks Gay. “Not get married and it would end? I didn’t want to end it. So the choice was made right there. She made the choice.”

By way of explaining how he felt about his wife-to-be, he tells me about his first love, a girl he met in college in Alabama. “She was my Zelda Fitzgerald,” he says wistfully. Gay was devastated when she dumped him. “When I met Nan, I thought, this is a person that I’m not going to be dumped by. And that mattered to me. In a practical sense, I wanted to succeed, and I wanted to have someone who cared about me personally, and Nan did. And I cared about her as well. I just felt I could grow with her. I’m not sure I could have grown with little Miss Zelda Fitzgerald.”

Nan did her best to ease Gay’s passage from bachelorhood to family life. “I thought that it was my responsibility to take care of everything that involved marriage,” she says. “He paid the Con Ed and the rent bill and anything he would have had to pay anyway. I would pay for the groceries, the nanny, and everything to do with the children. I never wanted to be a burden on him. I knew he always wanted to be free.”

But there is another story from their marriage, one of a more recent vintage, that suggests Mrs. Talese is not exactly a pushover. Nan, who does not love the Jersey shore, where the family has a beach house, recently bought a country home in Roxbury, Connecticut. “I’m terribly happy there,” she says. “It took me months to get up the courage to tell Gay I bought it.”

He didn’t know?

“No!” she says, and then explains that Gay had, in fact, vetoed the purchase. But a few months later, when he was out of town, she bought the house anyway, with her husband none the wiser. Finally, one Sunday morning, when they were eating breakfast and reading the paper, she screwed up the courage to tell him. “Oh, I have some news for you,” said Nan. Then, very casually, as if she were talking about a sweater she’d picked up, she said, “I bought that house in Connecticut.” Gay’s eyes grew wild with rage. He stood up and yelled, “Divorce!” and then took the paper and retreated to his room on the top floor. A couple of hours later, he reappeared. “Well, the sports cars will fit in the garage, won’t they?” he asked. Nan said simply, “Yes,” and they never brought it up again.

“You had a different kind of male edge to you,” Pamela Talese says to her father. “And the Nanster was doing her Betty White number, denying that there was any problem.”

Talese is sitting under the naked lady with the rainbow vagina, talking about how his marriage almost fell apart. Perhaps because we are on our second strong cocktail, he seems particularly introspective today, even a bit despairing, as he reassesses some of the choices he’s made. “I can only blame myself,” he says. “It was a case of me being … so uncareful. And Nan was unhappy. She might have told you she was not unhappy and it didn’t bother her—I don’t know what the hell she told you—but I’m telling you, from my point of view, that was the beginning of a lot of problems in this marriage. That book. Or the research of that book.”

I tell him that Nan did, in fact, have a different version, one that included her saying she trusts him. “Nan is very supportive. She won’t turn against me and say, ‘You can’t do that.’ On this marriage book—Jesus—she said, ‘What do you know about marriage?’ But she’s not saying, ‘Don’t do it.’ She’s cooperating. But she has a little distance, like she did with the massage parlor.”

Does he have regrets about Thy Neighbor’s Wife?

“Am I sorry I wrote it? No, I thought it was one of my best books.” He is now sort of slumped down into the couch, speaking softly. “I’ll tell you what I did have regrets about. You know, you become very sad when you think—my daughters—I felt I couldn’t protect them from the bad image that I had as a result of what I was doing. It’s something that bothered me more than anything else in the seventies. Kids talk, and what do they talk about? This wretched father, that’s what they talk about.”

I wonder if he ever simply apologized to his family for his carelessness and excesses, but he makes it clear that this is not something one can simply apologize for. “Sometimes, within the marriage, you are vulnerable during arguments to have this one thing—my illustrious and decadent period of researching Thy Neighbor’s Wife—come up again and again. It can be twenty years later: ‘Oh, well, I had to put up with you when you were running massage parlors and running around with no clothes on in front of Aaron Latham in your stupid article in New York!’ But again, I don’t really care. And Pamela and Catherine don’t seem to care. And now Nan doesn’t care. But in those days, I’m telling you, it was a miserable time.”

Here, suddenly, his tone shifts and there is an edge of bitterness. As much as he feels guilty for embarrassing Nan, he is also jealous of the freedoms afforded in her world. “The writers she published, they did what they wanted. People like Philip Roth, and Pat Conroy—he writes about his drunken father in The Great Santini—Margaret Atwood, all the people she published had the freedom to be writers. And I didn’t feel any less motivated as a nonfiction writer. I wanted to really pursue material at a depth that fiction writers can by not naming names.”

Worse, he felt that some of these writers had turned against him. He was up for president of PEN back when Thy Neighbor’s Wife came out, but withdrew because of the backlash. “I lost the respect of a lot of writers,” he says. “That hurt me a lot. I didn’t want to be a pariah. I felt that I was in disgrace among the people I thought I should feel comfortable with no matter what the hell I did with my professional life.”

He remembers discussing his problems with Nora Ephron one night when she had come to the townhouse for dinner. “This is the shittiest year I’ve ever had in my life,” he told her. “What are you going to do next?” she asked.

He didn’t quite know. He had thought he would write a book about Lee Iacocca and the car industry—“My idea was to get away from sex,” he says—but when his best friend, David Halberstam, announced he was embarking on a similar project, they had a falling out that lasted thirteen years. On top of that, he felt like a bit of a fool in Nan’s literary world. “I wasn’t sure that my marriage was supporting me. Nan was doing very well. I wasn’t doing very well. She was going about her life pretty easily and I felt, I’m losing my best friend.”

And so he left town. “I didn’t have any sense of what my personal life was, all I knew is that I had to have a professional life to bail me out.” He went to Italy to begin work on Unto the Sons, interviewing relatives of his father in a tiny hillside village in Calabria. He hired an interpreter, Kristin Jarratt, a 25-year-old blonde from St. Louis who was living in Rome. Their working relationship quickly turned into an affair. “I needed a friend,” says Talese. It lasted for most of the time Talese was working on the book, and Jarratt actually lived in the Taleses’ Ocean City house for a while when he was interviewing his relatives in America. “She helped me become very comfortable with who I am,” says Talese. “I wasn’t feeling comfortable with who I was at all in 1982, not after the whole Thy Neighbor’s Wife situation.” Jarratt eventually married and then divorced an Italian film director, and she and Gay remain friends.

Were you in love with her?

“Yeah.”

Did Nan know about it?

“Nan never asked too many questions, and I didn’t volunteer too much information. But there wasn’t any sneaking around. There were no secrets. And I never thought, I want to leave Nan. I was very unhappy. But what made me unhappy wasn’t Nan’s fault. I don’t know whose fault it was. My career just fell apart, and I fell apart a little bit.”

One evening, Talese and I are sitting in the living room when suddenly his daughter Pamela appears. Like her sister and her parents, she is intense, very attractive, a bit eccentric, and sharp as a tack.

“Want a little vodka?” asks Gay.

“I’ll sit down for a second, but I’m not going to have any vodka because then I won’t be useful for the rest of the day.”

“Do you want me to fix you a drink?” he persists.

“No, thank you,” she says, comically firm.

Pamela’s sister, Catherine, had always seemed to embrace the “crazy cricket rules,” as she puts it, of her parents’ relationship. “Life with them has been incredibly lucky and interesting and glamorous and it’s always felt like, this is unique,” she tells me. With her father, she says, “you could be putting mail in the mailbox, but you knew there was going to be an adventure.” And she sees her mother as his perfect complement: “She always said to me when I began dating, ‘Hold with an open hand.’ That’s not a life lesson, that’s a Zen lesson.”

But I wondered whether Pamela’s take was the same. After all, she was older, and more aware, when Thy Neighbor’s Wife came out. Before I can even think of asking so personal a question, Gay shifts in his seat, and his voice changes. “We were talking about Thy Neighbor’s Wife,” he says to his daughter, “and he asked me, Did we ever have a discussion about how you were affected by it?”

“It didn’t even enter your mind at the time,” says Pamela, matter-of-factly. “At about 8 or 9 or 10 years old, you began to tell me—with some pride, I now realize—that this book was going to get a tremendous amount of attention. And that we had to be prepared for it, but I actually don’t think that you yourself were prepared for the kind of reaction the book would get.”

“The book came out …”

“When I was 16,” she says. “That I remember distinctly.”

“Am I correct in that many of your fellow students would talk about me because their parents were so appalled by this decadent father of yours?”

“Of course. But Chapin [where she went to school] was so discreet. I was told later that in one English class somebody wrote a poem about you. But the teacher said, ‘It’s not to leave this room.’ And I could feel everyone being tremendously careful with me. The teachers kept coming up to me and asking me if I was … all right.”

A big smile spreads across Gay’s face. “Is that right?” Then he continues with his questioning. “Did you ever remember talking to me about it?”

“No, because you weren’t really available for that kind of conversation at that time. And I don’t know that I would have been able to articulate it even if you were. You weren’t the gentle nice person you are now. You had a different kind of male edge to you. And the Nanster was doing her Betty White number, trying to make everything okay and denying that there was any problem. In fact, both of you were doing that.”

Pamela starts to talk to me about her sister’s photography, and Gay, no longer the center of attention, gets bored and interrupts her. “I’m still impressed with the fact that I don’t have any knowledge of this: Did your mother ever take you aside during the post–Thy Neighbor’s Wife period and try to justify me to you? Did she say, Daddy’s a reporter or writer? Did she ever try to explain it to you?”

Pamela’s voice sharpens into a tone that parents use to negotiate with teenagers. “How honest do you want me to be?”

“I don’t care,” he says, a bit louder. “At this point, I don’t care.”

“From my point of view, where you two were at that time, you were not capable of addressing the kind of impact that that book not only had on me but the impact it had on both of you. I think that book shook you both down more than you probably recognize.”

“Then why are we still married after 50 years?”

“Because you’re stubborn.”

He looks at me. “What did she say?”

You’re stubborn, I say.

“Nan is sort of aloof, she’s very intellectual,” says Pamela. “She’s very in her head most of the time, and you were pulling that whole Telly Savalas seventies man, sex-without-strings number for most of my life, which didn’t do me any favors, by the way. I think you two are weirdly connected, and there’s really nothing you can do about it, because what you two have gone through together would have destroyed most marriages. And I think, also, in the seventies there wasn’t recognition of the way interpersonal relationships worked. Mommy would never have the language. She would never use a word like ‘co-dependence.’ The language just wasn’t there for her to recognize what was going on. I don’t know what would have happened—and I’ve thought about this—if you and Mommy had gone to therapy after the book. Would you have had a better understanding of each other or would you have gotten divorced? But the kind of strain you each put yourselves under … I mean, that book was a tremendous challenge because not only were you doing things that were unorthodox socially and otherwise, but you had the expectation that people would get it—in the press and in the larger world.”

Gay looks chastened. He sits there for a second, taking it in, and then says, “Did you read the book?” Yes, she says, in college. “Did you put a brown wrapper over the damn cover?” No, she says, she read it in her dorm room. He asks her what she thought of it. “I thought it was a wonderful book. Didn’t I tell you?”

“No. Never. All these years I’ve been wondering.”

Heeeelleew. Nan breezes into the townhouse just after 7 p.m. Still holding her bags, still wearing her trench coat, she and Gay engage in a hilarious mix of high-end literary talk, couple shorthand, and gentle argument. She mentions that Terrence Rafferty raved about one of her books, The Glister, by John Burnside, in The New York Times Book Review that comes out on Sunday.

“Oh, wow,” says Gay. “Rafferty’s a good writer.”

“He’s so intelligent, and he got across everything I kept trying to tell people about the book. And he comments on this certain unknowingness in the book—not exactly vagueness … And I thought, that’s the difference between you and me.”

“What’s the difference between you and me?” says Gay, startled by this shift into the personal.

“You are very specific and comfortable with the specifics,” says Nan. “And I am very comfortable in the fog.” Gay looks mystified, and Nan heads up stairs to take a bath.

Gay says to me, “Did you get that on tape?”

I did.

“That’s great. That is very much 7:30 dialogue in this house.”

Gay and I head to Brio, their neighborhood spot just a few doors down, where he and Nan are to meet old friends: the actor Ben Gazzara, his wife Elke, and Midge Richardson, the former editor-in-chief of Seventeen. Gay tells me where to sit and then orders a Bombay martini. Soon everyone arrives and gets busy drinking. Before long they are all shouting over one another.

Nan leans in close to me and says, “Imagine if this was the surface you landed on every night when you came home.” Earlier, she had lamented Gay’s constant need for social engagement: “A tuna-fish sandwich with the dogs and Masterpiece Theatre—that’s my idea of heaven.” How do you do it? I ask her. “I take a swan dive into the tub and join him because I want to be with him.” I ask her about her dogs. “They are very cheerful,” she says. “That is my rule: cheerful. You have made me think about this, the way he and I are different. I live in the fog—the opposite of rules. Fifty years and I have never been bored. But like Candide, I screen everything out.”

Suddenly Gay hands her the rest of his second martini. She looks at me and says, “I have been ordering drinks that are compatible with his forever because he can’t finish the second half of his drink and he insists that I drink it.” Nan, by the way, is now pretty lit. Actually, everyone is. Out of the blue, a man with long gray hair appears at our table with a guitar and starts to sing in Italian. Elke, a German with a tiny dog hidden under the table and an Ivana Trump aspect, knows every word to every song. Her husband has tears in his eyes. “This is the most fun I’ve had in five years,” he says. Elke and Midge get up to dance, while Ben translates the lyrics for Nan and me. Now more people have joined in, including two young, very sexy Italian girls.

Gay, who is now out of his seat and leaning against the wall next to our table taking all of this in, has the most curious look on his face. “He never lets down his guard,” says Nan, genuinely amazed by her husband’s reaction. “He’s really happy.”

The guitar player starts into “Grande, Grande, Grande,” a popular song in Italy that reached number one in 1972, the same year Gay began to work on Thy Neighbor’s Wife. Nan watches from the table as Gay dances off to join the others. The song floats through the restaurant.

You’re worse than a spoiled kid, you always want the last word.

You’re the most egotistical, overbearing man I’ve ever known.

But there’s some good in you.

At the right moment you can become someone else.

In an instant you become wonderful, wonderful, wonderful and I forget all my worries.