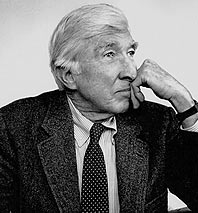

Terrorist, in which a New Jersey high-schooler, a “radical loser” right out of Hans Magnus Enzensberger’s much-discussed essay in Der Spiegel, agrees to a suicide-bombing mission on behalf of radical Islam, may not be first-rate John Updike. Updike is 74 years old, and he’s been spinning his wheels for a while. But they are wheels nevertheless, not blunt instruments. If Seek My Face (2002) didn’t convey anything new about Jackson Pollock, it had fun verbalizing an alternative abstract art. Villages (2004) may have been yet another of Updike’s many anthropologies of Northeast-seaboard mating dysfunction and existential dread, but who else would have elaborated a psychology and phrenology of golf swings, noticed the “thoroughbred ankles” of the hereditary rich, and plotted a trajectory by the games a man learns to play, from box hockey to bridge to cunnilingus? By now, too, we should have learned to stay alert every time he leaves his neighborhood. Brazil (1994) was one example, a magic-realist comic opera in which romantic egoism fared no better among shamans and jaguar gods than it had in the French Revolution. The Coup (1978) was more to the immediate point, since it is the only other Updike novel that quotes the Koran and was written from the African Muslim point of view of Colonel Hakim Félix Ellelloû, a student in the United States before he became president of sub-Saharan Kush. This colonel articulated my favorite sentence in all of Updike: “I perceived that a man, in America, is a failed boy.”

Ahmad Mulloy, the 18-year-old terrorist himself, is the latest in a long line of Updike boys failing their way to manhood, the only child of an exchange-student father long since returned to Egypt and an Irish-American mother who works as a nurse’s aide. On his own, loving prayer— “the sensation of pouring the silent voice in his head into a silence waiting at his side”—Ahmad has decided to be purer than the Koran. He will be used by the Yemeni imam who insinuates him through the suras and by the Lebanese furniture salesmen who employ him to drive the truck of fertilizer and racing fuel intended to blow up the Lincoln Tunnel.

But Ahmad wants to be used. Like most teenage boys, he’s as full of self-righteousness as of hormones: a luminous jerk. Like most Updike males, he is attracted to and revolted by the material and sensual worlds—in short, a romantic egoist. Is God “closer than the vein in his neck” even when he’s playing soccer? Surely “the Straight Path” leads away from Joryleen Grant, the black girl with eggplant breasts who’s probably a Baptist. Yet his single experience of sex is “a convulsive transformation, a vaulting inversion of his knotted self like that, perhaps, which occurs as the soul passes at death into Paradise.” A creature of surges of terror and exaltation, a martyr-in-waiting and “close neighbor to the unimaginable” who wonders if his own faith is just “an adolescent vanity,” Ahmad feels, approaching the tunnel, that the sunstruck world around him is “a glistening bowl of busy emptiness.”

Some of this is quite funny. Some of it is Red Guards and Hitler Youth. Some is Simone Weil—the indignation, empathy, and masochism. And much is standard-issue Updike, so the high-school guidance counselor is a tired virtuous Jew (“the oldest lost cause still active in the Western world”) who thinks about Abraham and Isaac in the accents of Kierkegaard and Dante. And his fat wife is all wrapped up in Updike’s own “Lutheran Daddy-Bear God” when she isn’t watching the daytime soaps. Whereas Ahmad’s mother, who will have a listless tryst with the guidance counselor, is a lapsed Catholic: “If Ahmad believes in God so much, let God take care of him.” Which leaves Joryleen, who isn’t in church, but, rather, even closer than God to the vein in Ahmad’s neck when she sings, “What a friend we have in Jesus.”

Unlike every other novelist looking over his shoulder at 9/11, Updike isn’t writing from the victim’s point of view.

Once again, sex and religion. The characters in Terrorist may be sketchy, and the action perfunctory, and the stereotyping wearisome, but Ahmad stirs up sediment in us. (Didn’t Rabbit Angstrom explode himself from overconsumption?) As in the best fiction, we are made more complicated. And who else among his godless peers but Updike would read the Koran so attentively, listen to the voice of God in “His magnificent third-person plural,” hear tell of the words of the Prophet invading human softness like a sword, ride with desert winds and robed warriors under cloudless skies toward crushing fire and the day “when man shall become like scattered moths and the mountains like tufts of carded wool.” Only someone who believes as much in water, light, and God as he does in the words that denote them can take a sacred text as seriously as medicine.

Unlike every other novelist looking over his shoulder at 9/11—an Ian McEwan, a Reynolds Price, a Jay McInerney, a Jonathan Safran Foer—Updike isn’t writing from the victim’s point of view. He guesses instead at unhinging excruciations. Finally, Terrorist has to be read as part of an accumulating literature in which serious novelists have tried to grope their way into the mind of the ultra, a literature that began with Dostoyevsky, Joseph Conrad, and André Malraux and continues with Don DeLillo, Richard Powers, and Salman Rushdie, trying to explain the phenomenon of what Victor Serge called “the lunatic of one idea,” as he shape-shifts from Belfast to Beirut to Jakarta to lower Manhattan, from skyjacking jumbo jets to bombing abortion clinics, from Pol Pot to Shining Path. Terrorists and torturers tend to be more interesting in novels, where they have complicated rationales, than they are in banal person. To think about horrific behavior, novelists need to imagine minds as nuanced as their own. So they pile aesthetic patterning and gaudy mythomanias on top of abstract grievance. They gussy up these kamikazes of Kingdom Come with Oedipus, Freud, Marx, Fanon, Dante, and Bluebeard, as though seeking a subjective correlative for the fabulous derangements of Gonzalo Thought.

But horrific behavior is perfectly capable of writing its own novel, of spinning its own excuses for abduction, torture, rape, and murder out of a spidery bowel and a smoked brain. Its cold, invariable, contemptuous purpose is to dominate and humiliate; to create, as in the nightmares of Kafka and Foucault, a lab-rat labyrinth, a “total immersion” maze, where our private histories, personal beliefs, and multiple motives are beside the brutal point. What we really need the Updikes for is to remind us, over and over again, that each fragile human being, every Rabbit or Ahmad, is an end, not a means.