D ave Eggers’s new novel is best introduced with a list of what it does not contain. There are no charts, no pages left intentionally blank, no cartwheeling paragraphs that stand out for their high concentration of whimsical exclamation points. No footnotes, no apologia, no marginalia, and not a single grieving white male of high education and questionable maturity. In short, there are exactly zero indicators alerting us that we are in the midst of an Eggers production; yet one finishes this wrenching and remarkable book with the impression that it’s precisely what the author’s past work—his foot-stomping memoir, A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, the quieter fiction that followed, the expansive literary subculture he’s created through McSweeney’s—has been building up to.

What Is the What tells the story of a refugee from the second Sudanese civil war (1983–2005), one of the 20,000 so-called Lost Boys who walked thousands of miles from their decimated villages (their homes burned by Arab militiamen, most of the adults slaughtered) to relative safety in Ethiopia and later Kenya. In a region with no shortage of unimaginable horrors—the ongoing genocide in Darfur has taken some 300,000 lives with no signs of abating—the particulars of the Lost Boys have long stood out as a crushing reminder of the primitive cruelty of African warfare. Few were older than 10 when they were displaced, and many died during their journey, some of starvation and dehydration, others at the mercy of lions and armed forces. It is a tragedy related by the extraordinarily clear-eyed Valentino Achak Deng, one of 4,000 refugees offered sanctuary in the U.S. in 2001, who is reflecting back while trying to survive an altogether different struggle: assimilation into a culture defined by its short-term memory and chronic indifference to the world beyond its borders.

Billed as a novel, What Is the What is more a work of imaginary journalism: Valentino is an actual refugee, whom Eggers spent years interviewing. “This book is a soulful account of my life,” states Valentino in a preface, explaining that Eggers wrote the book by “approximating my own voice and using the basic events of my life as the foundation.” The story opens with Valentino living in Atlanta, attending college, working at a health club, and having doubts about life in America—a state that’s compounded when his apartment is robbed and he’s beaten by two (black) Americans. This saga is juxtaposed with the brutal epic of his past. “When I first came to this country, I would tell silent stories,” Eggers writes. “I would tell them to people who had wronged me. If someone cut in front of me in line, ignored me, bumped me, or pushed me, I would glare at them, staring, silently hissing a story to them. You do not understand, I would tell them. You would not add to my suffering if you knew what I have seen.” And so while silently addressing his assailants, a disinterested cop, an ineffectual hospital staff, and so forth, Valentino describes in riveting detail his prewar village life, his devastating journey, his refugee-camp adolescence, and his early experiences in America, which include being adopted by generous Christians, befriending a Hollywood producer, and having a troubled reunion with the woman he loved in Sudan.

That Eggers gravitated toward this subject is fitting: He is, famously, a lost boy himself. His phenomenally successfully memoir chronicled how, at 21, both of Eggers’s parents died of cancer within weeks of each other, leaving him to raise his kid brother. In radiant prose, Eggers told an original, funny, life-affirming story of death and the orphan experience: the anger, the alienation, the premature loss of innocence, the bipolar urge to create community (Please understand me!) only to reject it (You’ll never understand!). Then there was the book’s sub-narrative, its overzealous need to operate as a metacommentary on itself and twentysomething solipsism in general. But if A.H.W.O.S.G. sometimes failed to transcend the precocious navel-gazing it critiqued, its shortcomings highlighted a noble impulse in the author: Eggers was eager to shift his focus outward, and the incidental theme of his career since has been his attempts to figure out how to pull this off.

Look at McSweeney’s. At first, the quarterly was an extension of the memoir’s self-referential, outsider aesthetic; now the writing is more varied, and there’s a book imprint, tutoring centers, a monthly magazine (The Believer), and a DVD magazine showcasing short films (Wholphin). Eggers’s own writing (You Shall Know Our Velocity!, a novel; How We Are Hungry, stories) has centered on thirtyish Americans (he’s 36) trying to get out of their own skin, away from their own grief, often by traveling abroad and immersing themselves in cultures plagued by more than existential concerns. Then, in 2004, excerpts of what promised to be Eggers’s forthcoming biography of Valentino (then using the name Dominic Arou) were published in The Believer—the product, it appeared, of his own such travels. As dispatches they were excellent, but one had trouble imagining them coalescing into an entire book. Eggers was writing in the first person (“In all the times I’ve traveled with or otherwise spent time with Dominic”), which inevitably made him part of the story.

To be your own most famous and enduring character is the fate of any talented memoirist; to escape it is how you prove yourself as a novelist. Whether this prompted Eggers’s decision to rework the material as fiction is something only he can answer—whatever the reason, the results are stunning. What Is the What is a portrait of a character that forces us to examine our world and ourselves, and how our struggle for identity is more of a collective battle than we’re often willing to admit. For all the bleak territory covered, the novel is also a reminder that remembering is both a form of sacrifice and salvation. To forget, Valentino says, “would be something less than human.”

BACKSTORY

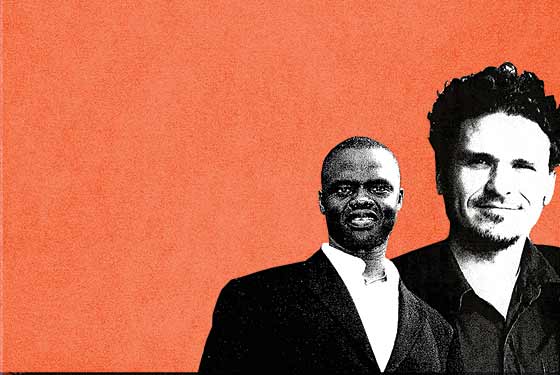

Africans are beginning to write their own great novels about the continent’s civil wars and lost children, but the best known are a generation—and an adopted country—removed. Last year, young Harvard grad Uzodinma Iweala published Beasts of No Nation, a harrowing tale told by a preteen boy conscripted into brutal service by guerrillas. Born in the U.S., he’s the son of a prominent Nigerian family—as is Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, who left for the States at age 19. Her new, epic second novel, Half of a Yellow Sun, is set against Nigeria’s civil war over Biafra, and features a 13-year-old boy who narrowly avoids the fate of Iweala’s haunted narrator.

What Is the What

By Dave Eggers. McSweeney’s. 386 pages.