For four years now, Continuum’s 33 1/3 series has been issuing a steady stream of hip little rock-and-roll catechisms: idiosyncratic pocket-size meditations by eminent critics on seminal albums. Subjects skew toward the artsy-intellectual (Radiohead’s OK Computer), the canonical (Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited), and the cultish (Neutral Milk Hotel’s In the Aeroplane Over the Sea). Among such countercultural titans, the series’s newest topic—Céline Dion’s Titanic-era Let’s Talk About Love—feels alarmingly out of place. Dion is the Antichrist of the indie sensibility, an overemoting schmaltz-bot who has somehow managed to convert the ethos of Wal-Mart into sine waves and broadcast them, at kidney-rupturingly high volume, directly into our internal soulPods. A book pondering the aesthetics of Céline risks going wrong in about 3,000 different ways. Most obviously, it could degenerate into one of those irritating hipster projects of strategic kitsch-retrieval, an ironic exercise in taste as anti-taste in which an uncool phenomenon is hoisted onto a pedestal of cool simply as a display of contrarian muscle power.

Instead, this book goes very deeply right. Like most rock critics, Carl Wilson—a writer and editor at Canada’s national paper, The Globe and Mail—has always reflexively detested Céline. “From the start,” he writes in Let’s Talk About Love: A Journey to the End of Taste, “her music struck me as bland monotony raised to a pitch of obnoxious bombast—R&B with the sex and slyness surgically removed, French chanson severed from its wit and soul … Oprah Winfrey–approved chicken soup for the consumerist soul, a neverending crescendo of personal affirmation deaf to social conflict and context.” (As another critic once put it: “I think most people would rather be processed through the digestive tract of an anaconda than be Céline Dion for a day.”)

But while most critics would leave Céline there and go back to gushing over the lost tapes of the live versions of early takes of Dylan’s unwritten B-sides, Wilson feels a twinge of critical conscience. Pop criticism’s sacred duty, after all, has always been to articulate the secret genius of the underappreciated—an approach that’s given us our cherished canons of rap, rock, and manga. (Not to mention films and novels.) So what about Céline? In a critical climate that venerates slick, hyperproduced Top 40 pop, why is she immune to praise? Is her ululatory arm-flinging really so unforgivable? To find out, Wilson embarked on what he calls “an experiment in taste,” undergoing solid months of Céline immersion in an effort to get to the bottom of his “guilty displeasure.”

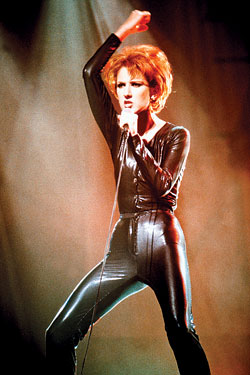

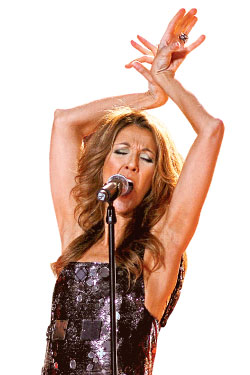

The Céline phenomenon, in Wilson’s telling, runs surprisingly deep. It was forged in the weird pop-cultural fires of seventies Quebec, a provincial bubble in which news anchors and earnest troubadours were venerated as mainstream heroes, while variety-pop stars were shunned. Céline emerged as a white-trash child star frequently mocked in the press for her “bushy hair and snaggle teeth.” She was also possessed, of course, with that Voice, an inhumanly powerful blast that annihilated the competition at cheesy global talent contests (the 1982 Yamaha World Popular Song Festival in Tokyo, the 1988 Eurovision Song Contest in Dublin) and made her manager cry, mortgage his house, and eventually marry her. Wilson is very good on the uncanny disjunction at the heart of Dion’s talent—that goofy, gawky frame, whipping its arms around like a t’ai chi instructor on a badly scratched DVD, unleashing crescendo after sublime crescendo. “She is at once doing tricks with her voice and is herself overwhelmed by its natural force,” Wilson writes. He also argues that Céline’s music is essentially aspirational, like rap: “Her voice itself is nouveau riche”—it’s “a luxury item, and Céline wants to share its abundance with her audience.” One of the book’s fun surprises is the odd way in which this abundance has distributed itself across the globe. Her French work is allegedly nuanced, understated, and literary; she’s beloved by the cabdrivers of Ghana and the ruffians of Jamaica; and she unknowingly endorses questionable products in the market stalls of Afghanistan (“Titanic Making Love Ecstasy Perfume Body Spray”). Even in the U.S., Céline has won the admiration of an improbably large roster of music-industry visionaries, from Rick Rubin to Phil Spector to Timbaland to Prince (who reportedly saw her Vegas show three times).

Wilson’s real obsession here is not Céline but the thorny philosophical problem on which her reputation has been impaled: the nature of taste itself. What motivates aesthetic judgment? Is our love or hatred of “My Heart Will Go On” the result of a universal, disinterested instinct for beauty-assessment, as Kant would argue? Or is it something less exalted? Wilson tends to side with the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, who argues that taste is never disinterested: It’s a form of social currency, or “cultural capital,” that we use to stockpile prestige. Hating Céline is therefore not just an aesthetic choice, but an ethical one, a way to elevate yourself above her fans—who, according to market research, tend to be disproportionately poor adult women living in flyover states and shopping at big-box stores. (As Wilson puts it, “It’s hard to imagine an audience that could confer less cool on a musician.”)

Although Wilson never grows to love Dion’s music, he’s also no longer comfortable with his former scorn. He acknowledges the merits of her work: “It deals with problems that don’t require leaps of imagination but require other efforts, like patience, or compromise”; although it is “lousy music to make aesthetic judgments to,” it “might be excellent for having a first kiss, or burying your grandma, or breaking down in tears.” And he ends the book with a Céline-inspired plea for a new species of “democratic” criticism: “not a limp open-mindedness” but a refusal to indulge in our baser cultural-capitalist instincts. Céline, he says, “stinks of democracy,” and his effort to understand her has taught him to “relish the plenitude of tastes, to admire a well-put-together taste set that’s alien to our own.” After all, every genre, no matter how hip, is subject to criticism. Early in the book, after a concise history of schmaltz (which he defines elegantly as “an unprivate portrait of how private feeling is currently conceived”), Wilson turns the notion back on its critics. “You could say that punk rock,” he writes, “is anger’s schmaltz.”

Near, Far…Wherever You Are

Astounding tales of Céline’s global semantic flexibility, from Carl Wilson’s book.

IRAQ

Sympathetic Soul

“Everyone loves Céline Dion,” an artist told the Omaha World-Herald. “They see her as the pinnacle of sadness. Her songs speak to the plight of the Iraqi people.” The U.S. has broadcast her songs “to show the West’s softer side.”

QUEBEC

Local Heroine

In her home province, Céline has passed from “shameful hick” (once mocked in the press as “Canine Dion”) to “emblem of national self-realization,” a model for Quebec businesses.

CHINA

Diplomat by Proxy

When Canada’s culture minister visited China in 1998 to talk about maintaining diversity in the face of globalization, the Chinese government officially requested that Céline tour their country.

GHANA

Cupid

Céline is played by every taxi driver and credited with popularizing Valentine’s Day in a country “where public displays of affection among unmarried couples are traditionally taboo.”

JAMAICA

Alert! Alert!

If you hear Céline in Jamaica, run: Her music, blasted at high volume, has become sonic wallpaper in bad neighborhoods, according to music critic Garnette Codogan: “It became a cue to me to walk … faster if I was ever in a neighborhood I didn’t know and heard Céline Dion.”

Let’s Talk About Love: A Journey to the End of Taste

By Carl Wilson. Continuum International Publishing Group. $10.95.