Forget Harry Potter. The real sea change in young people’s reading habits over the past ten years has come not from the boy wizard—whose unreplicable success was a lightning strike of fantastic storytelling, canny marketing, and dumb luck—but from a section of the bookstore that you likely ignore. Unless, that is, you’re 13 years old, in which case it might be the only section you patronize: the manga section.

Manga—pocket-size comics usually translated from the Japanese—are now a driving force in the young-adult market, with sales of over $220 million in the U.S. last year. It’s not surprising, though, that manga is overlooked by adults; the medium’s rows and rows of identically shaped books with confusing titles (Naruto? Hot Gimmick? Fruits Basket?!) are too alien for most adults to treat with anything other than a shrug and an “At least they’re reading, right?” But for typical young-teen readers, graphic storytelling is now as familiar a language as traditional chapter books—and one they expect to find in bookstores, not on spinner racks.

As barriers to the acceptance of mainstream graphic storytelling are falling, two writers—Brian Selznick, author of The Invention of Hugo Cabret, and Jeff Kinney, creator of the “Diary of a Wimpy Kid” series—have seized on the shift in young people’s reading expectations to make enormous hits out of books that mix comics and literature in clever ways. The yearlong residence of Hugo Cabret and the “Wimpy Kid” books near the top of the Times chapter-book best-seller list—typically populated by the usual suspects of young-adult best-sellerdom, like fantasy epics and li’l-chick lit—represents the first wave of a potential revolution in the YA market: the incursion of comics into “respectable” children’s fiction.

Of the two, The Invention of Hugo Cabret is the one that makes greater gestures toward high art. Set in 1931 Paris, it tells the story of an orphan who lives alone in the depths of the Montparnasse railway station. Hugo spends his days winding the station’s 27 clocks and his nights tinkering with a broken automaton—a mechanical man that Hugo’s father was fixing when he died. If Hugo can repair it, it is programmed by the springs and gears hidden within to come to life and write something—Hugo doesn’t know what—on a piece of paper. Hugo comes to believe that the note the machine might one day produce “was going to answer all his questions and tell him what to do now that he was alone. The note was going to save his life.”

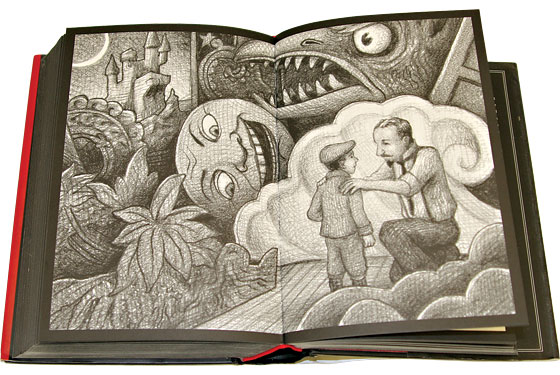

That what eventually springs from the pen of the automaton is not text but an iconic image is fitting, since in Hugo Cabret, pages of workmanlike prose serve only to propel the plot forward. When action or wonder is required, Selznick switches to his secret weapon, handsomely shaded two-page pencil drawings: of Hugo being chased through the bowels of the Gare Montparnasse; of Hugo and a girl gazing at the lights of Paris from inside the great glass-faced clocks in the station’s tallest tower; of Hugo in a dark theater staring, rapt, at the flickering light of a movie. Silent films are just one of the curiosities in which the novel takes a young person’s obsessive interest; the automaton is another, as are Hans Christian Andersen fairy tales, windup toys, sleight of hand. At times, the impeccably curated cultural touchstones seem a bit artificial, as if Selznick had made a product-placement deal with the Cinémathèque Française. But the carefully selected details make Hugo Cabret feel like, well, a machine, full of tiny interlocking parts, built to fuel a curious child’s lifelong infatuation with wonder.

The concerns of Greg Heffley, the star of Jeff Kinney’s Diary of a Wimpy Kid, seem more prosaic than Hugo’s. Greg isn’t a lonely orphan searching for meaning; he’s just trying to make it through middle school without sinking lower than his current social stratum, which he estimates at “somewhere between the 52nd and 53rd most popular.”

There are no gorgeous penciled panoramas or stills from Georges Méliès films here. Kinney doesn’t use his art to provoke awe, or even to move the plot forward; the books are marketed as “novels in cartoons,” but the more appropriate description might be novel with comic strip. Kinney’s stories follow a familiar setup-setup-gag structure, with the setup usually conveyed in text and the punch line delivered via simple but eye-catching line drawings.

For many young readers Wimpy Kid will be the more potent tale; Kinney remembers better than most adults the ferocious desire for popularity that drives kids this age. Even years later, you’ll ashamedly recognize the impulses that drive Greg to throw his gooney best friend, Rowley, to the wolves in order to raise himself in the eyes of his classmates.

At a time when so many children’s books are simply products rather than the product of passion—the heirs of “Goosebumps” and “Sweet Valley High”—it’s hard to imagine many eyebrows being raised by Cabret and Wimpy Kid, books whose success might ten years ago have provoked agonized “Arts & Ideas” articles about the debasement of children’s literature. It’d be nice, though, if parents who likely hope that their children’s obsessions might serve as a gateway to “real” books might also steer them toward real comics. Young readers who enjoy the “Wimpy Kid” novels could graduate to Jimmy Gownley’s “Amelia Rules!” series, one very wise in its treatment of the knotty emotional struggles of preteen-hood. And kids who love Hugo Cabret might have a sophisticated enough graphic sensibility to approach Shaun Tan’s recent The Arrival, an immigration parable that also illustrates its story in rich detail but, unlike Cabret, does away with words entirely.

The Invention of Hugo Cabret

By Brian Selznick. Scholastic Press. $22.99

Diary of a Wimpy Kid

By Jeff Kinney. Amulet Books. $12.95.