The vocoder—code name Special Customer, the Green Hornet, Project X-61753, X-Ray, and SIGSALY—started distorting human speech in earnest during World War II, in response to the excellence of German wiretapping. It worked by dividing a voice into its constituent frequencies and spreading it over ten channels, so that anyone who caught the message in transit would hear only noise. (German spies probably heard something like the droning of bees.) The cost of this security, however, was almost total destruction of the message itself: The voice, reassembled at the other end, came out sounding like a drunk robot. As Dave Tompkins puts it in his mind-altering new history of the technology—a book that has become a kind of underground legend in the ten years since he started working on it—the vocoder produced “an electronic impression of human speech: a machine’s idea of the voice as imagined by phonetic engineers.” Its early adopters were often driven to confusion, frustration, and existential dread. Still, the machine wound up robo-filtering some of the twentieth century’s most crucial conversations: FDR, Churchill, Truman, and JFK spoke through it to navigate D-day, the bombing of Hiroshima, and the Cuban Missile Crisis. Churchill, in particular, was a vocoder junkie. JFK, on the other hand, couldn’t figure out how to work its buttons. LBJ hated it so much he once threw his headset across Air Force One. The title of Tompkins’s book, How to Wreck a Nice Beach, is what the vocoder sounds like when it tries to say the phrase “how to recognize speech.”

The early vocoder was, on top of all this, fabulously impractical. Like most forties electronics, it suffered from pre-microchip elephantitis. The full military version weighed 55 tons and had a footprint, Tompkins writes, of “a three-bedroom home and a garage.” Its air conditioner stood nine feet tall and weighed 10,000 pounds. Moving it required a barge and an aircraft carrier. And yet it was also extremely delicate—a Rube Goldberg machine of nested analog technologies. Each vocoder unit contained, for instance, two turntables that would play vinyl records of random noise (produced by the Muzak Corporation) whenever someone spoke. For a conversation to work, those turntables had to be synchronized with another pair of turntables at the receiving end; if either of them was even slightly off, everything dissolved into gibberish. This meant that every vocoder required, in addition to those turntables, a superaccurate crystal clock with which to synchronize them. The crystal clock required, in turn, a special oven with which to stabilize its crystals. And so on.

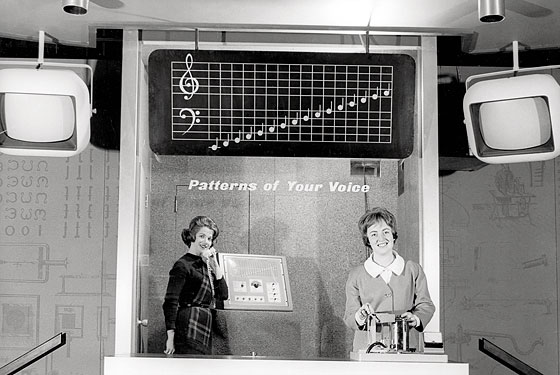

As America’s wars grew increasingly abstract—from World to Cold to Drugs—the vocoder shrank and became easier to manage. It went digital. It traded vinyl records for computer punch cards. Eventually it enlisted itself in all kinds of utopian civilian projects: voices for the speechless, a car that allowed paraplegics to drive with their larynx, the educational toy Speak & Spell. In the late seventies, the vocoder began to be marketed to the entertainment industry, promising the magical commodity of “instant robotness.” It made memorable aural cameos in Tron, Battlestar Galactica, and Transformers cartoons.

The vocoder’s most revolutionary effect, however, may have been in the world of pop music—particularly hip-hop and funk, whose pioneers (Afrika Bambaataa, the Jonzun Crew, Grandmaster Flash) managed to turn the machine’s inhuman croak into an instrument of weird paradoxical expressiveness. “The vocoder can be soft and sexy or powerful and demanding,” said a member of the band Midnight Star, whose 1983 hit “Freak-A-Zoid” came at the peak of what Tompkins calls “the vocoder space-helmet party of the eighties.” There were, of course, socioeconomic implications to all of these oppressed voices translating themselves into robo-speak. The vocoder, as Tompkins puts it, represented “the black voice removed from itself, dispossessed by Reaganomics, recession, and urban renewal, and escaping to outer space where there was more room to do the Webbo, where the weight was taken but the odds of being heard were no less favorable.” Today, the past’s voice of the future produces instant nostalgia: Every vocoder anthem I managed to track down on YouTube sounded like it should be playing behind a chase scene in Beverly Hills Cop.

Among the book’s many revelations is that the vocoder’s two cultures—the military and the funky—completely failed to speak to each other. “Of all the World War II cryptology experts I interviewed,” Tompkins writes, “none was aware of the vocoder’s activities in the clubs, rinks, and parks of New York City … Of all the hip-hop civilians I interviewed, none was aware of the vocoder’s service in any war.” It’s a nice irony, given the vocoder’s original function to connect people.

How to Wreck a Nice Beach is much more than a labor of love: It’s an intergalactic vision quest fueled by several thousand gallons of high-octane spiritual-intellectual lust. Outside of, say, William Vollmann, it’s hard to think of an author so ravished by his subject. Tompkins invites us to tag along on some of his adventures from years spent stalking the secret history of the vocoder. He interviews a 102-year-old retired crypto-engineer in Massachusetts, visits the Museum of Cryptology in Maryland, and hangs out for a disorientingly long time with a New York character named Rammellzee, a kind of funk-Dada artist-philosopher who seems to represent the vocoder as a lifestyle: He wears costumes armed with flamethrowers and lives in a kitsch-stuffed apartment he calls the “Battle Station.” Tompkins takes us on detours to meet the vocoder’s distant cousins: the Talk Box (a.k.a. the Ghetto Robot, Cosmic Communicator, Secret Magic Babbler), the Outer Visual Communicator (“a mouth-controlled virtual reality hologram machine”), and Auto-Tune (a technology developed by a former Exxon engineer and co-opted by Cher). The book has walk-on parts for some surprising figures: Ray Bradbury, Roald Dahl, New Kids on the Block, and Alexander Solzhenitsyn (he called the vocoder “an engineering desecration” but was forced to work on one for Stalin). And then of course there’s Tompkins himself, whose adolescence seems to have been scored entirely by the vocoder—he tells us, at one point, that the instrumental version of Fantasy Three’s “It’s Your Rock” was the first thing he heard after learning that his older brother had died.

The urge to manipulate the voice seems to be universal. “Ever since the first bored kid threw his voice into an electric fan, toked on a birthday balloon, or thanked his mother in a pronounced burp,” Tompkins writes, “voice mutation has provided an infinite source of kicks.” Tompkins is no exception. His biggest and most perilous adventure in How to Wreck a Nice Beach is the plunge deep into the throbbing radioactive heart of his own prose—a hallucinatory stew of Rimbaud, Tom Wolfe, Lester Bangs, and Bootsy Collins. The book is a kind of textual vocoder: Instead of giving us history straight, Tompkins separates the basic expository message into separate channels, beams them across his imagination, and reconstitutes them in a way that often sounds borderline insane. Sometimes the craziness is exciting, as when he describes the vocoder as “an articulate bag of dead leaves. A croak, a last willed gasp. A sink clog trying to find the words. Or the InSinkErator itself, with its wiggly, butter knife smile.” Sometimes it’s just baffling: “The polyphony reckons into the toxic highhold, an afterimage of burnt angels peeled from the eye”; “The lyrics quaver like algae’s grandmother.” In the second half of the book, Tompkins gets to flapping his funkodactyl wings a little hard for my tastes—especially given that his material, told straight, would have blown our minds several times all by itself. But, as with the Talk Box singer who fainted onstage after extending the word “baby” for 30 seconds, you have to admire that kind of dedication. Besides, it will probably all make sense in the robot-voice audiobook version.

How To Wreck A Nice Beach: The Vocoder From World War II to Hip-Hop, the Machine Speaks

By Dave Tompkins.

Melville House/ Stop Smiling. $35.