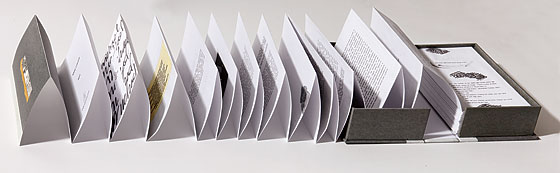

Few things in this world have the power to make me clean my desk. One of them, it turns out, is Anne Carson’s new book-in-a-box, Nox. Before I even opened it, I felt an irresistible urge to spend twenty minutes purging my worktable of notes, napkins, magazines, forks, check stubs, unpaid bills, and fingernail clippings. The urge struck me, I think, for a couple of reasons. For one, Nox is unwieldy. It is, very deliberately, a literary object—the opposite of an e-reader designed to vanish in your palm as you read on a train. It comes in a box the size of my external hard drive, and its pages fold out, accordion-style, to colonize all your available space. More than that, though, the book radiates a kind of holy vibe that seems to demand some gesture of ritual cleansing. It’s a public facsimile of a deeply private object: a scrapbook Carson put together as a memorial to her older brother, Michael, who died unexpectedly in 2000. New Directions has reproduced this unique collage lushly, in full color, with such thorough devotion that some pages show nothing but the backs of staples. Processing it, as a reader, seems to require several acres of clear space—mental, physical, emotional, attentional—every inch of which Carsonfills, immediately, with her own special brand of clutter.

Nox is a brilliantly curated heap of scraps. It’s both an elegy and a meta-elegy, a touching portrait of a dead brother and a declaration of the impossibility of creating portraits of dead brothers. The book opens with a puzzle: a wrinkled square of yellow paper containing a ten-line Latin poem—untranslated, unattributed, and unlabeled save for the Roman numeral CI. Anyone who is not (as Carson is) a classical scholar will most likely be stymied. But, right away, Nox begins to help. Its next page offers a dictionary definition of the poem’s first word, multas (“numerous, many …”), and this continues as the book moves forward: Most of Nox’s left-hand pages give dictionary entries that lead us, word by word, through the poem. It’s like an ancient linguistic detective story, or Latin 101.

Meanwhile, Nox’s right-hand pages keep piling up the scraps: photos, paintings, handwritten letters, passages from Herodotus, transcripts of conversations, international stamps. Carson threads these together with writing of her own until, little by little, a shadowy portrait of her brother begins to emerge.

Carson and her brother grew up in a nomadic Canadian family. (Their father was a banker, which meant—because of a policy that regularly rotated bankers among branches—they had to move every few years.) Anne focused her attention on books. Michael, who was four years older and referred to his sister as “Professor” and “Pinhead,” took a rougher path. He hung around older boys, usually ending up either injured or excluded. (Nox includes a heartbreaking photo of young Michael standing alone under a tree house full of boys who’ve pulled the ladder up behind them.) He went on to deal drugs, leave home, and drift through Europe and India under false names with a fake passport. He sent brief postcards but never an address. In 22 years, Carson writes, he only called a handful of times. He was, in short, a total mystery. When he died, Carson didn’t find out until two weeks later.

One of the pleasures of reading Carson is the way she applies the habits of classical scholarship—the linguistic rigor, the relentless search for evidence, the jigsaw approach to scattered facts—to the trivia of contemporary private life. In Nox, she treats her brother like a figure from antiquity who just happens to have grown up in the same houses she did and to have died 1,500-odd years after the fall of Rome. “There is no possibility I can think my way into his muteness,” she writes. “I study his sentences the ones I remember as if I’d been asked to translate them.” Michael is both extremely specific and a kind of Everybrother. “I wanted to fill my elegy with light of all kinds,” Carson writes. But her subject left mainly shadows, and Nox is full of them. In several of the book’s photos, the foreground is dominated by the shadow of an unseen photographer—a little human-shaped piece of night intruding on the day. “Prowling the meanings of a word, prowling the history of a person,” Carson writes, “no use expecting a flood of light.”

As the accordion of Nox unfolds, its material begins to resonate across many levels. It is an elegy stuffed with elegies. It contains, for instance, Michael’s own elegy—written in the form of a letter to his mother—for a girlfriend who died suddenly overseas, as well as the terse eulogy Michael’s widow delivered for him at his funeral (“I do not want to say that much about Michael”). Whatever new knowledge Carson gathers tends to trigger old memories. Her trip to the church in Copenhagen where his funeral was held reminds her of her dead parents: “both my parents were laid out in their coffins (years apart, accidentally) in bright yellow sweaters. They looked like beautiful peaceful egg yolks.” As the elegy rolls on, suspense builds around the most unlikely things. Will we ever see a picture of Michael as an adult? Will we ever find out how he died? Will we ever get a translation of that Latin poem? Eventually even the dry lexicography starts to smolder: It becomes clear that Carson is smuggling her own poetry into the dictionary entries, often in the form of illustrative sentences featuring variations on the word nox, Latin for “night” (“and do you still doubt that consciousness vanishes at night?”; “he lets in night at the eyes and the heart”). The entries turn out to contain, in condensed form, all the book’s major themes: presence, absence, violence, death, tribute.

Two-thirds of the way through the book, Carson finally solves for us the riddle of that opening Latin poem. It is Catullus 101, an elegy the Roman poet wrote in memory of his own brother, who also died overseas. “I have loved this poem since the first time I read it in high-school Latin class,” Carson writes, “and I have tried to translate it a number of times. Nothing in English can capture the passionate, slow surface of a Roman elegy. No one (even in Latin) can approximate Catullan diction, which at its most sorrowful has an air of deep festivity.”

This strikes me as the secret ambition of Nox, to produce a worthy translation of Catullus 101—not merely on a line-by-line level (although Carson does include her own moving translation of the poem) but in a deeper sense. Carson wants to reproduce, over the space of an entire book, the untranslatable qualities she most admires in Catullus: the passionate, slow surface; the deep festivity buried in the sorrow. She wants to reanimate dead things spoken in a dead language. “A brother never ends,” she writes. “I prowl him. He does not end.”

Nox

By Anne Carson

New Directions. $29.95.