Before dawn, on a mountainside in rural China, a 15-year-old doctors’ daughter from the city of Guangzhou starts hauling 80-pound sacks of earth and stones up to the top of a slope, where an army watchtower is taking shape. It’s 1968, two years into the Cultural Revolution. The girl, whose name is Chen Yi, has been torn from her parents, who are the sort of dangerously cultivated people Mao is determined to expunge. She has smuggled a violin into the mountains. Her beloved Bach is prohibited, so during pauses, she serenades farmers with elaborately filigreed improvisations on revolutionary songs. She embellishes Mao’s dictum, “Be resolute, fear no sacrifice, and surmount every difficulty to win victory,” with variations inspired by Paganini’s Caprices.

Four decades later, Chen Yi remarks that those improvised concoctions of revolutionary sentiment and bourgeois showmanship represented “my first try at composition.” Today, she is a professor of music at the University of Missouri–Kansas City, but those years in China’s heartland still permeate her refined orchestral works. In Chinese Folk Dance Suite for Violin and Orchestra, sweaty, ecstatic fiddling skips over a surface of rustic rhythms. The spirits of Bartók and Stravinsky lustily haunt the score, but so do those of nameless village musicians.

It’s either an appalling irony or delicious justice that attempting to crush a culture often winds up enriching it. Franco’s Spain was the gray progenitor of Pedro Almodóvar’s exuberantly colored movies. Stalin created the need for Boris Pasternak. In China, Mao’s attempt to cleanse the national culture of Western taint spawned a generation of resolutely hybridizing composers. Those musicians who, like Chen Yi, spent long stretches of their childhood sharing songs and labor with peasants, form the core of “Ancient Paths, Modern Voices,” Carnegie Hall’s festival of Chinese music and arts.

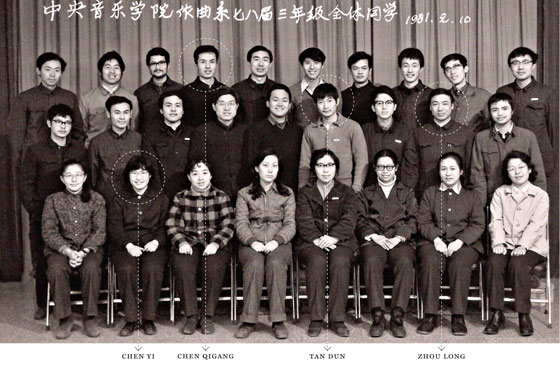

In 1978, when the Cultural Revolution had left the nation exhausted and multitudes dead, a few hundred musicians—including several dozen composers—were admitted to the newly reopened conservatories in Beijing and Shanghai. Suddenly, they were encouraged to distill their own musical voices out of timeless folk melodies, court traditions, Peking opera, and Western symphonies. Some—Chen Yi, her husband Zhou Long, Bright Sheng, Tan Dun, and Ge Gan-ru—later moved to New York, where they gathered in downtown lofts and Columbia student apartments to critique each other’s music and discuss the task of fusing the cultures of their native and adoptive lands. Most of them had been urban kids sent off to the countryside; then they arrived as rough-handed autodidacts in rigorous big-city music schools. Now they were outsiders once again, well-trained professionals with vast experience and sketchy English, mingling with graduate-student members of New York’s insular avant-garde. Back then, I, too, was a doctoral candidate in composition at Columbia, and although I have clear memories of Chen Yi’s permanent grin, Zhou Long’s deadpan stare, and Tan Dun’s impish bustle, I don’t recall them mentioning their Maoist reeducations.

Tan Dun moved to Chinatown and threw himself into the orbit of John Cage. He spent a lot of time exploring the resonances of ceramic bowls, which he schlepped up to Columbia to tap for his puzzled professors. In the West, he’s the best known and most theatrical of the bunch, having won an Oscar for his score to Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon and written a stage work, The First Emperor, for the Metropolitan Opera. Even his concert works package sound as spectacle. The festival features his Water Concerto, a study in drips and splashing grace notes, disposed to poetic effect. The range of timbres evokes antique rituals and gurgling gardens, but it almost suggests a vast magnification of the pipa, the Chinese lute whose notes ping and, with a poignant ripple, deliquesce.

Well before Mao, classical-music chinoiserie by both Eastern and Western composers had already produced an ample catalogue of clichés: pentatonic tunes played by massed violins, whooping glissandos, gongs, and allusions to ponds, clouds, and calligraphy. The younger generation has no interest in such pastiches. They have spent 30 years searching for deeper veins of content, and during that time, the cultural merger became a phenomenon as American as it is Chinese. Bright Sheng, who sat the feet of Leonard Bernstein, received a MacArthur “genius” grant in 2001 and is now a professor at the University of Michigan, made explicit reference to the Cultural Revolution. H’un (Lacerations): In Memoriam 1966–1976 opens with a scorching explosion of percussion and plucked strings. Woodwinds spark, strings buzz, and the orchestra shudders, offering a wild beauty but no solace. (H’un is absent from the festival, but the same concert that features Tan Dun’s Water Concerto also includes Sheng’s marimba concerto, Colors of Crimson.)

Not all the ’78ers went to America. The Carnegie extravaganza closes with the orchestral essay Iris dévoilée, by Chen Qigang, who landed in Paris and studied with the maître of twentieth-century French music, Olivier Messiaen. In Iris, the ear gravitates at first to the Peking Opera singer’s swoops, but you can detect a hint of Frenchness in the lushly clangorous instrumental textures and the sequence of solemn, stained-glass chords. Chen and his cohort were reared on nationalistic absolutes, but they move across borders with remarkable nonchalance. Techniques meld, dialects blur. Authenticity is not a goal, but a hard-won tool.

Ancient Paths, Modern Voices: A Festival Celebrating Chinese Culture

Carnegie Hall

Through

November 10.