In the first production of Rossini’s Armida to reach the Metropolitan Opera (and New York), Renée Fleming flicks a wand and transforms a creature-infested grotto into a palace of sensual delights. The Met’s general manager, Peter Gelb, must crave that trick right now to restore the health of his budget, his music director, and his aesthetic agenda, all of which are ailing. Yet Fleming’s wand couldn’t even jolt the opening-night performance out of its sloppy lassitude.

Gelb has been running the company for more than three years, but this is the first full season he planned, paid for, and delivered—a rollout of eight new productions, culminating with Armida and laying out a program of modernization that is supposed to save the art form. Always a couple of decades behind, the Met is only now junking its collection of ponderously pseudo-realistic sets in favor of the kinds of lean, abstract productions that seemed startling in the nineties. The strategy is fine, but its execution needs more muscle and judgment. Gelb has, for example, anointed the director Mary Zimmerman the doyenne of bel canto, and so far, she has turned in a Lucia di Lammermoor as a B-movie hoot, an incoherent La Sonnambula, and now an Armida that distills the worst of the Met’s current weaknesses: blind worship of unreliable stars, theatrical gimmicks that supplant dramatic conviction, and a flickering supply of musical electricity.

Rossini was a wizard of froth, but in this work, he slathered lacework vocalism on a putatively serious romance. The beautiful Armida bewitches the crusader Rinaldo, until his trusty officers deprogram him by appealing to his martial honor: Make war, not love. Zimmerman doesn’t know what to make of this material, except to encrust it with whimsy: Cue the red-garbed cherub descending from the ceiling. Add a twenty-minute dance of the demons, a field of plastic poppies, a phalanx of shiny helmets, and a fistful of forgettable tenors, and you have an overlong show that exists for one reason only: to glorify the name of Renée Fleming. Armida is a stage-scorching role, and she had great success with it in the mid-nineties, but the opera is better suited for a lighter voice, a smaller house, and a diva with fewer distracting affectations.

The current letdown follows a string of half-successes: Ambroise Thomas’s Hamlet, a wheezing touring vehicle for the marvelous baritone Simon Keenlyside; a visually laughable, musically exquisite Attila; and dutiful revivals of Simon Boccanegra and Stiffelio. Partly, the problem is that Gelb is a fervent expansionist in a time of contraction. If he had been able to power ahead with the projects he has had to cancel—expensive revivals of Berlioz’s Benvenuto Cellini, John Corigliano’s Ghosts of Versailles, Shostakovich’s Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, and Strauss’s Die Frau Ohne Schatten—the Met would feel less like a woozy Leviathan. He has also leaned on a roster of box-office stars who can’t be counted on to show up. Angela Gheorghiu, Anna Netrebko, Rolando Villazón, and Natalie Dessay all backed out of Met appearances. And the usually impeccably professional Leonard Slatkin, who had originally signed on to conduct the Corigliano, made a hash of La Traviata and skipped out after one performance. Sometimes Gelb’s spirit of innovation looks indistinguishable from confusion.

Gelb’s ambition to recruit creative minds from other fields is another good idea that has proven a wobbly cornerstone for the new Met. It did, however, pay off splendidly in Shostakovich’s The Nose, an acid comedy about a Moscow bureaucrat whose proboscis escapes and, worse, achieves a higher rank than its erstwhile owner. In a brilliant managerial stroke, Gelb assigned this work of immature, erratic genius to the artist William Kentridge and coordinated it with a major Kentridge retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art. The event looped the Met into the art-world circuit, lured a fresh audience, and tossed opera into the center of New York’s intellectual life. This is exactly what the Met should be doing.

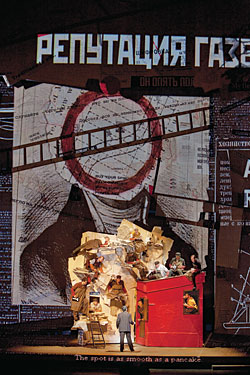

Kentridge responded to Shostakovich’s hectic, jangling score with a constructivist dream, a collage of shadows, ramps, three-dimensional puzzle pieces, headlines, and projections. Valery Gergiev led a biting, bristling performance, and if the volley of sounds and images occasionally felt like more than a brain could manage, the overload was strategic. At times, the score seemed less like the main event than a soundtrack for the staging, but The Nose can tolerate a slight rearrangement of operatic hierarchy.

The Met needs Gelb’s marketing savvy, but Gelb also needs a full partner, an artistic director as powerful and engaged as he is. For four decades, James Levine has kept the Met in a state of high musical readiness. He shaped the repertoire, led about 65 to 70 performances each season, cultivated singers, honed the orchestra, and left his thumbprint even on shows he didn’t conduct. The Met was Jimmy’s house.

Levine is only 66, but a series of illnesses and another job, as music director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, have interfered so seriously that his grip here has gone limp. He’s spent just a dozen nights on the podium since September and delegated the few big hits. Next month, he’ll miss his cherished revival of Berg’s Lulu. Next season—his 40th—he’s scheduled to conduct six operas, beginning with the opening-night inauguration of the new production of Wagner’s Ring. Now the festivities are tainted by doubt. Maybe back surgery will cure his suffering; maybe he’ll give up his Boston gig; maybe he’ll wrest back a greater chunk of his company’s aesthetic agenda. But for now, it’s just not Levine’s company any more. If Gelb is really the house visionary, he must know that it’s time to talk succession.

BACKSTORY

Even with swelling deficits and a withered endowment, Gelb is doubling down on his ambitions for the 2010–2011 season. Part one of Robert Lepage’s new production of Wagner’s Ring cycle opens this fall, followed by the company premiere of John Adams’s Nixon in China in an old staging by Peter Sellars. The other two genuinely fresh shows are Rossini’s Le Comte Ory, directed by Bartlett Sher, and Boris Godunov, directed by Peter Stein. In his goal to keep turnover high, Gelb will employ at least one budget-saving move: The “new” Don Carlo and La Traviata have already been seen in Europe.