In the first part of Richard Wagner’s “Der Ring des Nibelungen,” the god Wotan uses his sister-in-law as collateral for a new home. In a similar fit of recklessness, the Metropolitan Opera has bet its own house on a new “Ring.” The production by Robert Lepage, which will roll out over the next two years and serve the Met for many more (unless it bankrupts the company first), begins with a whiz-bang but verveless Das Rheingold, in which miracles of stagecraft alternate with long stretches of standing around, waiting for the computer-guided set to trundle into place. On opening night, it clanked and stalled, but those technical faults will be fixed more easily than the production’s conceptual emptiness. Lepage has spent years—and a reported $16 million of the Met’s money—figuring out how to get light and steel and acrobats to behave the way he wants them to. He seems to have given far less thought to why the characters behave the way they do.

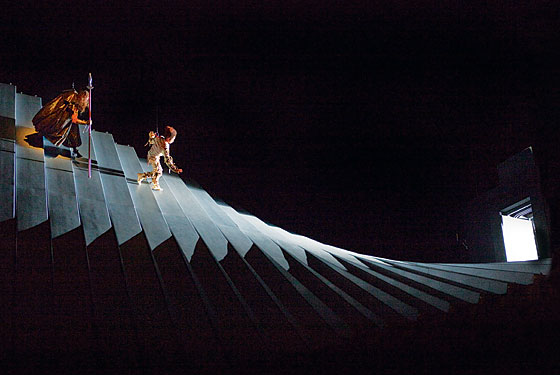

The “Ring” story covers generations of mortals, while the gods endure. A “Ring” production plows through casts, but the one constant in this iteration will be the set, a massive apparatus made of parallel swiveling beams that arrange themselves in various architectural and anthropomorphic forms, animated with digital projections. This sometimes works so well that gadgetry becomes character. In the opening scene of Das Rheingold, the beams oscillate to form the rippling surface of the Rhine. Then they tilt vertically and glow aquatic blue to become the depths, where three suspended maidens exhale projected bubbles as they sing. ¬Another turn of the machine, another projected image, and the maidens come to rest on the river’s pebbled bed, where every flick of their mermaid tails causes a graceful slippage of stones. A wizard who knows how to space out his tricks, Lepage one-ups the Rhine scene with the descent to Nibelheim, in which Wotan and his sidekick, Loge—or rather, their aerialist stunt doubles—descend a staircase that twists in midair like a Möbius strip.

Lepage’s choreographic virtuosity does not extend to humans. He is fortunate to have such a musically confident cast, because he leaves his singers physically stranded. The lecherous Alberich chases the Rhine maidens upstage, then has to pivot 180 degrees to inform the audience of his frustration. Fricka stands and frowns. Wotan stands and slouches, desperately gripping his spear. Everyone seems to be expecting the set to do another stunt. Surely it must be an illusion, but James Levine even seems to slow the beat now and then, to let the machinery catch up.

The atmosphere of torpor makes the occasional manic bursts all the more bizarre. Suddenly, the exquisite harmonic swirl thins, the moral vapors part, and a moment of rampant silliness is revealed. The goddess Freia makes her entrance by tobogganing—head first, belly down—along a ramp and vanishing into a ditch before popping up to sing: “Help!” On several occasions, Loge, the dangerous and darting god of fire, retreats up the same steel slope that Freia descended so the audience can see the flames dancing digitally at his feet. The play of light looks hot, fierce, and fast; Richard Croft, climbing backward, can’t help but make the nimble fire god seem tentative and slow. You get the feeling that Lepage would have preferred a virtual singer.

This is not a case of an arrogant director foisting a new narrative onto old music (no trench coats, no Hitler). Instead, Lepage tempers his innovations with such respect for Wagner that he leaves an interpretive void at the opera’s core. Maybe that’s exactly what the Met wants: an attractive, neutral vessel in which to decant the score. On opening night, the company filled it three-quarters full. James Levine, making a comeback from back surgery and plunging into his 40th grueling year of conducting at the Met, led a limpid, liquescent performance. His touch was evident not just in the smooth pour of orchestral sound or in the fearsome rattle of the giants’ tread, but in the Rhine maidens’ opening trio, the sort of intimate ensemble that Levine likes to buff until it becomes an object of bejeweled splendor.

As Wotan, Bryn Terfel tries mightily to radiate divine majesty, despite the bionic breastplate and metalhead locks that make him look like Mickey Rourke in Iron Man 2. He is not the only cast member to do battle with a costume. The giants, Fasolt and Fafner, clump around in outfits apparently scavenged from Planet of the Apes, Stephanie Blythe sings Fricka in a frog-green prom dress, and Loge prances in gold overalls with glowing bulbs in his palms. This is the bold new “Ring”?

The ever-professional Terfel focused on Wotan’s difficulties rather than his own. His aerodynamic bass-baritone glided through thick orchestral currents without ever veering into a bellow. His is a Wotan in his prime, petty of spirit and none too bright, but powerful of voice and will. The rest of the cast dropped hints of potential splendor. As the run rolls on, Blythe will surely juice her supernova mezzo-soprano with more Wagnerian indignation, and Croft will relax into a Loge who not only is conniving and clever but also truly enjoys his skill in handling the plot’s joystick. The charismatic Eric Owens already endows the cartoonish role of Alberich with at least two and a half dimensions, and he may yet shave off a few more ragged ends of caricature.

The Met has come to rely on technology, and the season opener was beamed live to rain-dampened audiences in Times Square and on Lincoln Center’s plaza. It’s too bad, then, that the production was still so buggy that the opera’s final apotheosis—the gods’ march over a rainbow into Valhalla—didn’t happen at all. That glitch, too, will be repaired, but the worry remains that the Met, like Wotan, has mortgaged its destiny for a property full of dazzle and ¬disappointment.

See Also

Slideshow: Anjelica Huston, Rufus Wainwright, and More at the Met’s Opening Night

Das Rheingold

By Richard Wagner.

The Metropolitan Opera.

Through April 2.