It seemed auspicious when a spectator who was not a candidate for angioplasty, and who was not especially fond of ballet either, slipped into the hall where Morphoses/The Wheeldon Company was rehearsing its inaugural performance at the Vail International Dance Festival in August. Her name was Marissa Miyamoto; she was 9 years old and had a green belt in karate. If her sports camp hadn’t been canceled, she would have been playing volleyball instead of hanging around the Vail Mountain School, where her grandmother worked and where, in the auditorium, the celebrated choreographer Christopher Wheeldon was setting new steps on fifteen of the finest dancers in the world.

At 34, Wheeldon is the boy wonder of classical ballet, having created more than 44 works for nearly every major ballet company. Last November, after six years as the first resident choreographer of the New York City Ballet, he announced he would not be staying on past the end of his contract in 2008 much less vying one day to run the company co-founded by the legendary choreographer George Balanchine. Two months later, he made an even more shocking announcement: He would be starting a company of his own.

The news made headlines—“Gambler Shakes Up Land of Tutus and Leotards”—because ballet in New York has been dominated for the last 50 years by American Ballet Theatre and New York City Ballet much in the way baseball in the metropolitan region is dominated by the Mets and the Yankees. As Michael Kaiser, president of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, D.C., bluntly put it, “How many great ballet companies have been started in the last 30 years? The answer is none.”

Wheeldon’s ambitious agenda was summed up on a T-shirt he was wearing during the company’s two-week residence at Vail this summer: STOP BITCHING AND START A REVOLUTION. Morphoses’ mission statement made so bold as to pledge the company would “restore ballet as a force of innovation.” And while self-effacing Englishmen are not by nature given to brash claims, Wheeldon has said the example he hoped to emulate was Diaghilev’s famous Ballets Russes, where the roster of collaborators included Stravinsky, Picasso, Balanchine, and Nijinsky.

“I never aspired to run City Ballet,” Wheeldon told me. “I’m not interested in inheriting a legacy; I want to create one of my own. There’s a big hole in the dance world right now. There’s not enough focus on bringing young people into ballet. One of the things I want to do is help audiences get over the idea ballet has some mysterious code they can’t decipher.”

In light of Wheeldon’s promise to cultivate “a broader, younger” following and embrace the paradox of democratizing an aristocratic art without debasing its refinements, Marissa Miyamoto was something of a preliminary test case. When the karate kid tiptoed into the auditorium, Wheeldon gave her a friendly hello.

“Do you take ballet?” he asked.

“No,” she said.

“Do you like ballet?

“No.”

Still she stayed. Came back the next day. Lingered all week in fact. Wendy Whelan, the City Ballet principal who was moonlighting with Morphoses for the summer (and will be part of the cast when Morphoses makes its New York debut at City Center on October 17), signed a pair of pointe shoes and showed her how to tie them on. Marissa seemed keen on the former San Francisco Ballet principal (and recent City Ballet hire) Gonzalo Garcia, because Garcia spoke Spanish just like her favorite singing group, the Cheetah Girls. Occasionally, troupe members working on new choreography with Wheeldon asked Marissa the steps she liked, and Wheeldon, who has always preferred the collaborative approach to the dictatorial, incorporated her choices. He offered Marissa and her grandmother tickets to the first Morphoses performance at the Vilar Center in nearby Beaver Creek. During the performance, she watched raptly. Whelan found her in the lobby afterward.

“So do you like ballet now?” Whelan asked.

“No,” Marissa said.

“But you like ballet dancers?”

“Yes.”

“And you like watching the ballet dancers dance?”

“Yes!”

“Well then—you like ballet!”

Still a bit wary of the implications, Marissa allowed herself to smile. The revolution was under way.

Many obstacles await a young choreographer bent on having his own company. It is not too much of an exaggeration to say that the only way to spend money faster than founding a ballet company is to start a war. Classical dance is, with opera, the most expensive of the performing arts. Toe shoes alone, without which ballerinas could not achieve the empyrean effect of being on pointe and distinguish themselves from the sublime savages of modern dance, cost $70 a pair and fall apart after a few hours of hard use.

Apart from the prohibitive costs, there’s the conundrum of cultural mind-share—how to get the attention of the wretches in the media and rouse the enthusiasm of an ever more distracted and, where ballet is concerned, seemingly indifferent public. “There’s a fundamental cultural shift that’s affecting all performing-arts companies,” said Ken Tabachnick, the general manager who oversees New York City Ballet’s $58 million annual budget. “Younger people do not find the value in performing arts that older people do. We’re still trying to understand and analyze it. We spend a lot of time talking about our education programs.” Wheeldon believes the younger crowd will come if he can convince them that ballet is “sexy” and “accessible” and not off-puttingly pretentious. He’s taking his sensual, athletic choreography to the iPod generation by blogging about the company. Morphoses even has a MySpace page.

But the most difficult obstacle may be the impossibly high expectations of the ballet world itself. For nearly a generation now, the art of classical dance has been suffering a kind of massive creative hangover. The death of many of the colossal figures of the twentieth century—George Balanchine, Jerome Robbins, Frederick Ashton—has, in the words of Damian Woetzel, the longtime NYCB principal dancer who just completed his first season as the artistic director of the Vail festival, “left the ballet world gasping for breath in the absence of established genius.” Gasping for breath and entertaining messianic fantasies of a savior who might not only have the gift to rescue ballet from what critic Jennifer Homans has called its descent into “sickly pieties and terminal athleticism” but also possess enough press appeal, marketing wizardry, and general Gen-X glamour to renovate its geriatric demographics and dwindling audiences.

Like it or not, Wheeldon is the leading candidate for the messiah job, largely because he is very talented, “the most talented classical choreographer of his generation,” the New York Times critic Anna Kisselgoff declared six years ago. It may be too soon to define his signature steps or say what is unmistakably the Wheeldon aesthetic—and it is certainly too soon to say whether his company will meet the critic Arlene Croce’s definition of a great dance company: “a vision of the universe and the individual’s place in it.” But to sit in an audience waiting for the curtain to go up on a Wheeldon premiere is to feel that uncommon crackle of anticipation. It’s the mystery of dance why some patterns of movement generate energy and communicate meaning while others send you to the lobby desperate for a drink. But where so much choreography seems about as interesting as watching a couple of aerobics instructors wrestle over a StairMaster at a tag sale, Wheeldon’s work makes you pay attention. His feel for music is keen; his steps are often witty; he paints vivid pictures full of inventive sculptural shapes and intricate sequences that don’t seem contrived. And the pas de deux for which he is acclaimed are exquisitely emotional, dancers unfolding in the glycerin of a dream.

It’s not as if it’s impossible to launch a successful new ballet company. The Miami City Ballet, founded in 1985 by Edward Villella, and Carolina Ballet, which began twelve years later, have enthusiastic regional followings, as does a group like lines Ballet, which was started in San Francisco 25 years ago and is dedicated to staging the work of its founder, Alonzo King. And of course small modern dance companies have proliferated in the last couple of decades.

But no one has attempted what Wheeldon is going for: a new, international ballet company with residencies in New York and London and an emphasis on the creation of new works. He hopes eventually to establish a collaborative group centered on some twenty world-class dancers, whose training and careers he would help shape, and that would also embrace artists from other disciplines (such as the fashion designer Narciso Rodriguez, who is designing the costumes for two new Wheeldon ballets being presented this week). The dance repertory would include classic works from contemporary ballet’s remarkably small canon and new pieces by choreographers other than Wheeldon.

It was, after all, another choreographer, William Forsythe, whom Wheeldon says helped precipitate his decision to leave City Ballet. The two men had bumped into each other in the summer of 2006 at the Lincoln Center Festival. “He told me in no uncertain terms, ‘It’s time for you to be on your own,’ ” Wheeldon recalled. “People are still confused about why I would walk away from City Ballet, where I had carte blanche. The press wants me to make it a big drama and say, ‘I couldn’t take another minute there,’ but it’s just not the case. It was just a question of me wanting to be in control of my own artistic destiny and of opening a new door.”

Ironically, Wheeldon had so much freedom under Peter Martins, the artistic director of New York City Ballet, that at times he found himself wishing he had less, hungry for colleagues to knock ideas around with and a creative environment that was not premised on the modernist idea of the artist as a lonely figure grappling with existential quandaries in solitude. (It’s probably worth noting that Wheeldon’s sense of isolation had been unpleasantly enhanced at the time by the breakup of a long-term relationship.)

“People at City Ballet never questioned my artistic vision, and maybe that is one of the reasons I wanted to leave,” Wheeldon said. “Peter feels artists need the freedom to discover for themselves and learn from their mistakes. The schedule is such that it’s hard to interact with other artists. Forsythe was telling me what it was like to be in a smaller group of dancers and to work collaboratively.”

And of course, as ever at City Ballet, there was Balanchine’s long shadow. After the debut of his January 2006 ballet, Klavier, set to the slow movement of Beethoven’s Hammerklavier sonata, Wheeldon had been particularly irked by the critics who rushed to point out that Balanchine considered Beethoven’s music unchoreographable.

“I’m so tired of people telling me you can’t do this and you can’t do that,” Wheeldon told me. “That whole stuff about how Balanchine said you can’t dance to Beethoven so nobody should bother choreographing to Beethoven really ticked me off. I wanted to shout, ‘Think for yourselves, people! There’s more than one way to do things!’ It was part of what made me want to have my own company.”

Exasperated by orthodoxies and spurred by Forsythe’s injunction, Wheeldon went to see Lourdes Lopez, a former City Ballet principal dancer who had retired from the stage in 1997 after a 23-year career. Lopez, who was born in Havana and fled with her parents when Castro took over, had co-founded the nonprofit Cuban Artists Fund and served as the executive director of the George Balanchine Foundation. Wheeldon’s seven-year tenure as a dancer at City Ballet (he was a soloist when he gave up performing to concentrate on choreography in 2000) overlapped with Lopez’s. “I remember him taking class,” she recalled, “but Chris and I never touched each other onstage.”

What had left an indelible impression on her was a piece Wheeldon choreographed for a studio performance by School of American Ballet students in 1996 (Danses Bohemiennes set to the music of Debussy). “I called my husband and said, ‘Holy shit’—excuse my French—‘I think we have here the next great choreographer. He was like 19 or something.” (Twenty-three, actually.)

Meeting last year, they discovered they shared the same ideas about dancers and the direction ballet ought to take. “Dancers are like horses or children,” Lopez said. “They have to be nurtured and led and guided and reprimanded and inspired. It’s the nature of the art. I remember when my moment came, Mr. Balanchine gave me a very important role in Violin Concerto—I was in the corps de ballet, and I was going out there with Peter Martins in front of 800 people. And I said to Mr. B., ‘I don’t know what you want!’ and he said, ‘I want you to be Lourdes!’ Dancing is not just something you do onstage on Sunday afternoon. It’s an entire career. ”

She signed on in September 2006 as the new company’s executive director.

With the family parrot, Chagall, frequently consulting from his cage, Lopez and Wheeldon worked out of the dining room of the Fifth Avenue apartment she shares with her husband, George Skouras, and their 5-year-old daughter, Calliste. The goal was to have a completely independent, fully operational ballet company by the end of 2009. They had to establish a board of directors, draft a business plan, design a logo, set up a Website, apply for tax-exempt status from the IRS, and name the company. Morphoses, Greek for “processes of transformation,” was the title of one of Wheeldon’s more innovative ballets. It seemed aptly suggestive of the troupe’s artistic ambitions.

Which, of course, required dancers. Morphoses wasn’t in a financial position to hire dancers away from companies where they had jobs, so Wheeldon planned to assemble casts on a pickup basis. More important was to drum up business, even though he had nothing to sell at the moment but his reputation. The first person he called was Alistair Spalding, the artistic director and chief executive of Sadler’s Wells, the premier dance venue in London. They met for a glass of wine in November. Spalding immediately offered a three-year contract for a two-week residency and four or so performances annually. Arlene Shuler, the president and CEO of New York City Center, which has a partnership with Sadler’s Wells, was equally enthusiastic and committed to a similar deal through 2009. And Damian Woetzel, who had danced in the debut of the ballet Morphoses in 2002, agreed to book the debut of the company Morphoses at the 2007 Vail International Dance Festival.

When Wheeldon announced the new company in January, Morphoses had locked up performance fees of $705,000 for its first season, and $3.4 million for the next two years. The fees were enough to give the venture a handsome start, but not enough to keep it going. The company was looking to raise $3 million to $5 million over the next few years. (The expense projections included $20,000 a year for pointe shoes.) Lopez and Wheeldon hoped to attract twenty “permanent founders” who could contribute $50,000 each to the cause.

In March, they took a train down to Washington, D.C., to see Michael Kaiser at the Kennedy Center. For more than two decades, Kaiser has given seminars on arts management, fund-raising, and marketing to organizations all over the world. He gave Wheeldon and Lopez a crash course.

“I was a little insulted it took them so long to call,” Kaiser joked. “I’ve known Chris a long time. What I told them basically was that the most important thing is the art, and the second most important thing is the marketing. To be successful, he has to create great art, and he and Lourdes have to market the hell out of it. It’s much easier said than done.”

By the end of April, Lopez and Wheeldon had raised $129,000, started a board, and ended Chagall’s lonely vigil by hiring an administrative assistant, 25-year-old Elizabeth Johanningmeier. The first gathering of dancers was a mock rehearsal in mid-May at the New 42nd Street Studios before a Bloomberg television crew producing a piece about Morphoses.

“We’re going to teach—Oh, what’s the name of my ballet? After the Rain,” Wheeldon said as the dancers were limbering up. “We’ll do a few moments where it looks like I’m correcting you all even though I never have corrections for you.”

The only trouble was the lack of traction on the studio floor.

“This floor is a nightmare,” Wheeldon said. “There’s not enough rosin on it. Does anyone have any Coca-Cola or something sticky?”

“The building owners will kill us if we put Coke on the floor,” Johanningmeier warned.

“That’s your job, Elizabeth. You’re fired—again.”

“It’s not a productive day if I haven’t been fired at least once,” she said, laughing.

“People at City Ballet never questioned my artistic vision,” says Wheeldon. “That’s one of the reasons I wanted to leave.”

There were problems too with the company’s first event, a low-key cocktail party and fund-raiser in June. About 200 invitations were sent out, each with a little convex plastic lens glued on to convey the theme of taking a closer look at the new company. But the unorthodox square shape of the envelope triggered a minor budget crisis when a seventeen-cent-per-envelope surcharge was imposed by the postal clerk. Then, on the night of the party, the caterer couldn’t get into the space. “Plan B was to get sandwiches and soft drinks from a deli,” Lopez said. And Johanningmeier had to make a pre-party inventory of furniture scratches, as if it was a known fact that balletomanes would not attend a cocktail party without their cats.

But everyone was happy with the turnout—Michael Kaiser came up from Washington; Alistair Spalding flew over from London, as did Peter and Judy Wheeldon, parents of the wonder boy.

Lopez introduced herself. “I’m the executive director of Morphoses. That should explain why I look so tired.”

“And why I look so fresh,” Wheeldon chimed in. He was wearing a white shirt embroidered with blue butterflies. Butterflies figured in the company’s early logo ideas, but the sketches all came back looking like perfume ads, so they settled on an image of a crouching ballerina with splayed arms, and were not amused to hear from anyone who thought the logo looked a lot like an Amazonian tree frog.

“Our mission,” Wheeldon was saying, “is to create a ballet company for the long term. We want to break down the traditional boundaries of the fourth wall, and allow audiences to get to know the dancers so it’s not such a mysterious and strange environment. Tutus and tiaras are beautiful, but we want to show ballet is also sexy and young.”

Wheeldon’s father looked on proudly. “Chris has been his own man since he was 12 years old,” he said.

That was the year—1985—when Wheeldon, a student at the Royal Ballet School, appeared in a production of The Nutcracker at Covent Garden and was singled out by Clement Crisp, the dean of ballet criticism in England, as “a bright spark” and “a neat buoyant dancer.”

Wheeldon grew up in Somerset, England. His mother studied jazz and ballet before developing a career as a physical therapist; his father worked as an engineer but had a keen feeling for music as a clarinetist and a member of a choir. Wheeldon devised his first dance when he was 8 and continued choreographing on the side when he became a dancer in the corps of the Royal Ballet in 1991.

It was an ankle sprain the following year that led him to the U.S. He was watching TV in his apartment, with a bag of frozen peas on his foot, when he saw a commercial offering anyone who bought a Hoover vacuum cleaner a free ticket on Virgin Airlines. Wheeldon bought the vacuum and promptly flew to New York with a suitcase of clothes and tapes of dance pieces he’d choreographed. He got permission to take class at City Ballet and not long afterward was invited by Peter Martins to become a member of the corps de ballet. He was promoted to soloist in 1998 but retired from performing two years later to choreograph full time.

During that first year as artist-in-residence, Wheeldon was out of sorts after a gig choreographing Vivaldi’s Four Seasons for the Boston Ballet. He hadn’t felt connected to the music. His friend, former City Ballet principal Jock Soto, told him to find a piece of music that wasn’t conventionally pretty or romantic—ideally something that frightened him. What came of the advice was Wheeldon’s Polyphonia, set to the tumbling, discordant piano music of the Transylvanian composer György Ligeti. (Wheeldon would always send his father a CD of the music he was working on to listen to in the car, and when Peter Wheeldon heard this, he nearly drove off the road.) The ballet Ligeti’s music had inspired was Wheeldon’s breakthrough, his first risk-taking essay in a choreographic voice entirely his own and, in many ways, the precursor to what he is undertaking now.

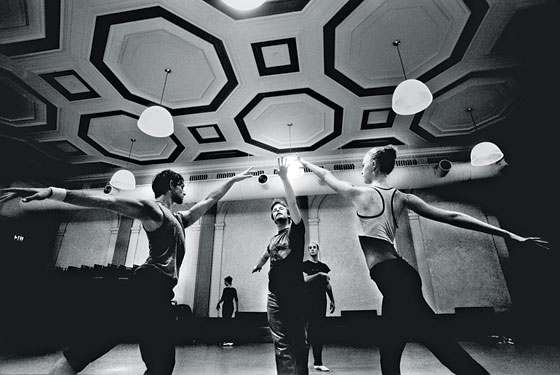

The new company arrived in Vail the first week of August, dancers flying in from San Francisco, New York, Rome, and Hamburg. There were fifteen principals, plus eight young ballerinas from the Colorado Ballet who had been imported to dance corps roles in the Dance of the Hours, an upbeat, angst-free ballet Wheeldon had choreographed for the Metropolitan Opera production of La Gioconda and wanted to present at Vail as his closing number. The company was all billeted together at the Highlands Lodge in Beaver Creek. “It felt like summer camp,” Lopez said.

Every morning, there was class led by ballet mistress Olga Kostritzky, moonlighting from the School of American Ballet in New York. Kostritzky rode herd on the local girls, trying to sharpen their timing and attack. Their technique was more constrained than the featured dancers’. “They will never forget this,” Kostritzky said later. “For two weeks, they have tasted freedom. And when this is over, they will have to go back into their cage.”

Wheeldon rehearsed some of his old ballets and plunged into creating two new pieces he would show at Vail as workshop performances, then give official premieres at Sadler’s Wells in September and at City Center in October. Watching the rehearsals, Lopez was struck by the difference between the dancers of Wheeldon’s generation and the dancers she grew up with.

“My generation needed father and mother figures,” Lopez said. “The dancers of this generation need a friend. We had mentors. They don’t need mentors. Chris is like a brother to them—an older brother.”

Whelan, who is six years Wheeldon’s senior and often seems to act in the capacity of his big sister, thought the role he had carved out for himself was half a brother, half a dad, and started calling him “Brad.”

The critic Jennifer Homans perceptively put her finger on this theme in the New Republic three years ago, writing that Wheeldon’s aesthetic grips younger dancers in a way that Balanchine’s does not. “Balanchine embraced the elevated aristocratic moeurs of nineteenth-century ballet; his dancers had grace, manners, and above all style. They were fascinating and eccentric artists, and he gave their musical and theatrical instincts ample reign … Wheeldon’s dancers are an entirely different breed. Their bodies are opaque, stripped of social identity: not déclassé, but classless … They are not personalities but modeling clay—classically trained but tempered with a yoga-like, organic quality.”

The audience at Morphoses’ first show at the Vilar Center in Beaver Creek—a select crowd of 280—was so primed they gave Wheeldon an ovation just for walking onstage to introduce the night’s program. In keeping with the company’s goal of demystifying ballet, the lights came up on the dancers arrayed as if in their morning class, as Wheeldon, like a tour guide, explained the routine, condensing what would typically be an hour and a half of warm-up exercises, barre work, and jumps. The second half of the evening was given to performances: Wheeldon’s Polyphonia and After the Rain, along with excerpts from two of Wheeldon’s works-in-progress, a short duet by Edwaard Liang, and Wheeldon’s Dance of the Hours. After the show, Vicki Bromberg Psihoyos, who danced with City Ballet for a dozen years, had to catch her breath. “The thought I had,” she said, “was that we were witnesses to history, like the people on the Warburg lawn who saw Serenade”—Serenade being the first ballet Balanchine choreographed in America, using students from the School of American Ballet in 1934. The next night, at the Gerald R. Ford Amphitheater in Vail, Wheeldon took a bow as the crowd of several thousand fervently clapped and shouted.

Vail, as it turned out, was like the womb that delivers the new fawn into the mouths of the waiting wolves. British wolves for the most part, who were not much impressed by the sheer fact that a new dance company consisting of only four people—Lopez had just brought in a bookkeeper—not only had managed to secure three years of booking fees and raise (by this point) $300,000 but also had put on fourteen ballets (three of them world premieres) by six different choreographers with 30 of the world’s best dancers in a matter of months.

Some of the reviews from Morphoses’ run at Sadler’s Wells were exceptionally harsh. The Daily Telegraph called the evening “so prim and buttoned-up” that it turned “what was a white-hot ticket into a very lukewarm attraction.” London’s Daily Express said Wheeldon “is going to have to do better than this if he wants to grab the attention of young people untutored in either classical or contemporary dance.” The Sunday Telegraph compared one of the costumes Wendy Whelan wore to “a giant Pringle.”

Probably the worst review came from Clement Crisp, the critic who had singled out Wheeldon 22 years ago for his “buoyant spark” and in the past counted Wheeldon among his small list of “life-enhancing” choreographers. In the Financial Times, Crisp professed himself fiercely disappointed by a “relentlessly pauperish show, its manner anxious, its costuming singularly hideous, its effects small-scale and morose. Will this bring in the new audience Wheeldon seeks? I incline to doubt.”

“Vail was our innocent time,” Wheeldon said last week, a note of weariness in his voice. He was worn down and running a fever thanks to the exhausting rehearsal schedule leading up to the City Center debut. “It was the time before we were judged. It was a wonderful supportive audience and a great creative coming together. Now, the heat is on. If the expectations weren’t so high, the pressure would be much less.”

It has been a hard lesson in image management. Wheeldon, who had set the bar high with his initial proclamations, now seemed to want to ratchet it down a bit. The invitation to next week’s inaugural gala at City Center includes some cautionary thoughts: “My fear is that some people may be expecting too much from us in the beginning. My vision is something that may not be fulfilled for five or six years … Dreams take time.”

I asked about the Crisp review.

“Over the years, Clement has been very supportive and completely destructive,” Wheeldon said. “I don’t think that it is easy for Clement to review contemporary work in his mid-eighties.”

I said I thought he was 76.

“Well he’s almost in his mid-eighties. It’s a different generation. He was brought up on Fontaine and Nureyev and the Royal Ballet. He has very different standards. He’s a very funny writer, but it’s become just about that rather than really looking at work. The only thing that really bothered me was the crack about reconsidering what a younger audience would want. I honestly think I know more about what my generation would like to see.”

He sighed. “We’ll continue regardless of Clement.”

The ability to withstand criticism is surely another of the elements of a successful ballet company. City Ballet might not exist if Balanchine had taken the New York Times dance critic John Martin to heart when he said that the nascent organization that had mounted Serenade on the Warburg lawn should “get rid of Balanchine … and hire a good American dance man.”

For Wheeldon it is an article of faith that the process is as significant as the final product. Much of what he wants to do with Morphoses is change how dances are made. “The last three or four months have been incredibly enriching in this respect,” he said. “My dancers felt they were part of the creative process, part of the vision. It’s easy to not feel this way when you’re in a big company. Even the critics who didn’t like some of the pieces could see that the dancing was extraordinary. It made me feel really good about my philosophy.”

This resolve is more important to Lopez than a couple of bad reviews. “I think there was a question in Chris’s mind whether it was possible to have a company,” she said. “Not just a gig, or a pickup group, but a real company. I think when he saw how everyone danced in Vail, and how they came together and grew, it cleared him of any lingering ambivalence. The bug bit him. He knows he could close the door and go choreograph anywhere in the world. But that would be a disappointment to him now.”

The company has made at least one major change in the wake of the London performances: Chagall, the parrot, has been moved out of the dining room, where he will not be able to interfere with important phone calls or indulge in various other counterrevolutionary acts. The future of ballet was too important to let it be sabotaged by a parrot.