At the glass palace that is Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater’s headquarters, Judith Jamison is literally enshrined. Her regal profile greets visitors in a huge 1969 photo with Alvin Ailey, the company’s benevolent patron saint, arm clasped about his disciple. There’s a painting here, a towering mosaic there—on every floor, her image oversees the school’s goings-on. Ailey, who passed away in 1989, may have laid the foundations for the country’s preeminent African-American dance company, but it is Jamison who has succeeded in fiercely ensuring the survival of his legacy. Not only that, she’s accomplished something no other dance company in the country can claim: turning Ailey into a bona fide brand.

The company starts its winter season at City Center this week, and with it begins Jamison’s last full year as artistic director, a position she’s held for twenty years. The company without her is unfathomable. Jamison has been inextricably tied to Alvin Ailey since she was 22, first as Ailey’s muse—she’s widely considered his greatest dancer—and then as the successor he anointed to articulate his mission. “Alvin would have hated that word, ‘mission,’ ” Jamison says with a laugh. “It gets used because we’ve turned into an organization, so therefore we have a mission. I think vision is the word, because he was a vi-sion-ary.”

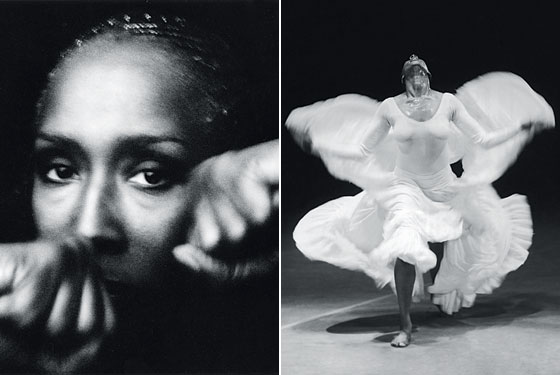

Jamison has a habit of enunciating words in a self-consciously humorous and vaguely teacherly manner. (She is called Ms. Jamison. Never Judi.) Draped in scarves and a black silk smock, bald but for a bit of gray peach fuzz, the 66-year-old still looks remarkably like the towering, five-foot-ten dancer who defied standards of beauty and electrified audiences with raw emotion, particularly in 1971’s Cry, the breathless, sixteen-minute solo Ailey created for her, and 1960’s Revelations, Ailey’s iconic ballet set to Negro spirituals.

Yet even in her role as artistic director, Jamison plays to the audience—an attitude she’s passed down to her school’s dancers. “She definitely wants us to be aware of what we represent, and that’s this lineage Mr. Ailey started, which she’s continuing,” says Matthew Rushing, a seventeen-year veteran of the company. “She enforces that to the point where there’s a way she wants us to carry ourselves outside the theater and the school: in airports, at receptions, traveling.”

She is also, to the dismay of some critics, dedicated to pleasing audiences. Jamison embraces television as an ideal medium to show off the company (it’s made appearances on So You Think You Can Dance and Dancing With the Stars)—an unpopular tactic with the lofty modern-dance set. Others complain that Ailey’s work became repetitive after Revelations; it is rightly the company’s most famous piece but, to some minds, a peak Ailey never quite reached again. “If people all over the world, year after year, request that you do Revelations, you do Revelations,” Jamison scoffs. “It’s ridiculous. I mean, Alvin had no problem being pop-u-lar. Dance comes from the people, and we want to make sure it stays with the people. It’s not some highfalutin somethin’ or other. And it’s not that it’s easy—but it should be accessible.”

That notion of accessibility—artistically and personally—might end up being Jamison’s legacy: the idea that dance should be the most democratic of art forms because of the basic, honest human impulse that drives movement. Jamison’s students and colleagues speak unanimously to her generosity of spirit. Rushing met her at his audition for the Ailey School, in Berkeley, California. “She made a point to give people shout-outs during the audition,” he says. “To let us know if we were doing well, to correct us if we were wrong, like a rehearsal situation. I remember she yelled at me: ‘I’ve never seen double tours that fast in my life!’ I started laughing, and I can’t tell you how nervous I was.” Ronald K. Brown, whose modern-dance group Evidence is very much in the Ailey mold, remembers an early Evidence performance at a small church on the Lower East Side. Jamison arrived before the chairs were even set up. “I was blown away that she’d come to this small venue to support the work, and she’s been an incredible support since,” says Brown, who will stage his fourth piece for Ailey—Dancing Spirit, a tribute to Jamison—this season.

Jamison will also be sharing her twelth new work for the company, Among Us (Private Spaces: Public Places). There must be some poignancy in that. “Nooo!” she cackles. “I was thinking, Last ballet I’m ever gonna do! I don’t have to go through this again, I don’t have to do this to myself!” Jamison is partially kidding; she’s admittedly “attached at the hip to this place.” And she doesn’t consider this an ending but a beginning for the company—the chance to let fresh ideas in. “I came to the conclusion that I believe in the past, present, and fu-ture of the company!” she says. A colleague recently pointed out to her that in the 50 years Alvin Ailey has existed, the company has had only two artistic directors. “Me taking a glissade to the left, or to the right, so to speak, to make space for the future is important,” she says, noting that her replacement has not been determined. “I have my ideas of what I’ll do, which are very private. But I’m certainly not drifting off into the sunset. I love the man—I still love him. He gave me the greatest gift, and I’m not walking away from that.”

She would, however, like a new title—something more glamorous than artistic director emerita. “Queen? Your Majesty?” she says with her big laugh. “Something like that would be nice.”