It was the winter of 1999, and Amy Poehler was in a grimy bathroom on West 22nd Street, pulling used condoms out of a toilet. For three years, the 28-year-old Poehler and her fellow members of the Upright Citizens Brigade comedy troupe—Matt Besser, Matt Walsh, and Ian Roberts—had been performing sketch and improv anywhere they could. Now, thanks to Rudy Giuliani’s anti-porn crusade, they had their own theater in a defunct strip club. “The women’s locker room was all Prince mix tapes and bikinis,” Poehler remembers. “It was as if there’d been a nuclear disaster and everyone had just turned into dust and left all their shit behind.”

Poehler, Besser, Walsh, and Roberts (a.k.a. “the UCB Four”) had moved to New York from Chicago in 1996, a time when Manhattan’s comedy scene was in the first stages of gentrification. The city’s stand-up scene was thriving, but many of its nervier sketch troupes—most prominently Exit 57 and the State—were winding down, and long-form improv was all but nonexistent. On TV, Saturday Night Live was at the tail end of a weak period; Seinfeld and Friends, though set in New York, were strictly Los Angeles products. But in downtown Manhattan, scruffy young comics were coalescing around venues like Luna Lounge, Surf Reality, and KGB’s Red Room. Their style was free-form and deliberately unslick, and almost by accident, they fashioned a movement, one that would be given the vague tag of “alternative comedy.”

When the UCB Four came to town, their goals were to get a TV deal (which they did, two years later) and maybe pay the rent by teaching improv classes. But along the way they fomented a slow-burn pop-culture coup. The performers who took over that strip club—and, later, the UCB’s current main stage on 26th Street—would go on to populate Saturday Night Live, Late Night With Conan O’Brienn, The Daily Show, Human Giant, The Hangover, The Other Guys, FunnyorDie.com, and about three-fourths of NBC’s Thursday-night-sitcom roles.

It was more than just a talent mill, though. The UCB Four’s comedic style was distinctively absurdist, marked by an understanding that being gross and being smart were not mutually exclusive. Above all, it was highly collaborative, built around tightly bonded teams of improv comics, especially as the best students in the classes began to graduate and form teams of their own. “They were filling some kind of void,” remembers Conan O’Brien, an early booster and occasional guest star. “There were people—and I was one of them—who thought, ‘I’m less interested in doing stand-up. I really want to create weird things with other people.’ ” You could get as crazy as you wanted, as long as there was truth underneath the weirdness—and so long as you stuck with your team. That all-together-now asininity permeates comedy today, from improvised podcasts like “Comedy Bang Bang” to 30 Rock. “In Anchorman,” says director Adam McKay, an early UCB member, “when they go to the gang fight and there’s a guy with a trident and people getting killed—the Upright Citizens Brigade spirit is behind that.”

To mark the fifteenth anniversary of the UCB’s arrival in New York, and to inaugurate the UCBeast—the troupe’s second New York stage, which just opened in the East Village—we spoke with more than 50 UCB alumni, from stars who have moved to Hollywood to local heroes still going for laughs onstage here. “UCB is part high school, part rehab, part training camp, part substitute family, part junior college for life,” says Poehler, “and you have to figure out how to manage this high school without anybody blowing it up.”

PROLOGUE: CHICAGO

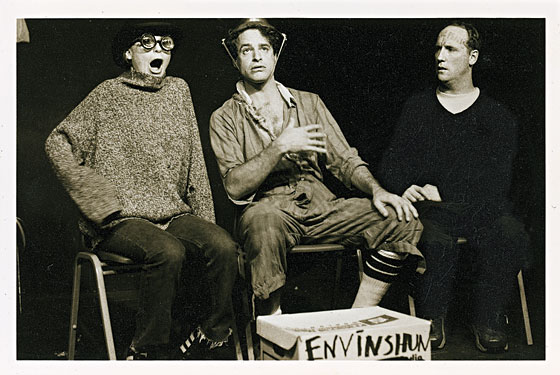

The Upright Citizens Brigade began in 1991 as a loose collective of Chicago improv and sketch performers, most of whom studied under the comedy guru Del Close. Through 1993, the fluid membership included Besser, Walsh, Roberts, Ali Farahnakian, Horatio Sanz, and McKay.

HORATIO SANZ: We had no respect for any other comedy enterprise in Chicago. I’m sure we weren’t liked for that.

ALI FARAHNAKIAN: We all had a similar vernacular, a similar collective unconscious.

ADAM McKAY: We were legitimately fucking delinquents. There were a lot of people in the improv scene who wanted to kick our asses.

ANDY RICHTER, Conan: I got along with them, [but] I seem to remember them getting thrown out of a lot of parties. They were incorporating a lot of hip-hop braggadocio, which was in contrast to a lot of the beer-drinking, Cubs-fan improv guys.

SANZ: For the first couple of shows, my friend from high school would stand in the back with a stun gun and a lab coat, and we’d say, “If people leave or get out of control, they will be dealt with by one of our assistants.”

McKAY: The first UCB show we ever did was called “Virtual Reality.” We would pluck someone out of the audience, and they would go with me and a cameraman in a car around the neighborhood—like we were doing sort of a Jack Kerouac drive around the country. Then we’d quickly edit the tape and show it to the audience ten minutes after we got back.

FARAHNAKIAN: We were doing shows on Fridays at midnight, in a pretty sketchy area of Chicago.

MCKAY: Besser chose who would go with me, and once, just for the hell of it, he gave me this guy who would show up at all of our shows—a sweet guy, but clearly a little off. We go to a fast-food place, which I pretty quickly realize is full of Latin Kings. They get in our face, and you could clearly see under their shirts they have guns. Meanwhile, I’m doing this sort of beat-poet character, and I’m with this guy who is basically mentally ill. [One of the gang members] takes these cheese fries I’ve ordered as part of the bit, whips them against the window of the place, and starts freaking out.* He’s not wired to handle this. So I stay in character—“Heyyyyy, peace, brother. It’s cool, man”—and we just get out of there, with them chasing us. [On the videotape], you could tell something very uncool happened. It went from gangbangers coming up to me, to a jump-cut edit, to us in the car racing back to the theater. And the audience was blown away.

ARMANDO DIAZ, performer-teacher: What they lacked in polish, they made up for with being really ballsy. There was a bit where Horatio was leading a protest, and he got arrested …

SANZ: [Congressman] Dan Rostenkowski had ruled Chicago for a very long time, and he was being indicted. So we lit up torches and got the audience—probably 50 or 60 people—out on the street.

MATT BESSER: We were on the busiest corner in Wicker Park with lit tiki torches and real-looking fake handguns, and we had stopped traffic. The police pulled up immediately.

SANZ: I had that split-second decision of whether to go, “Oh, sorry, we’re just doing a show,” and I decided to just keep going with it. My idea was, “How awesome would it be to be arrested in front of this audience, and have them thinking, Did they plan this? How did they get that cop car? What’s going on?” So I just kept chanting, “Kill Rostenkowski! Fight the power!” as they were throwing me in this cop car. After the car pulls away, I’m like, “I’m an actor, by the way.” I spent the night in jail.

*This article has been corrected to show that the cheese fries in McKay’s anecdote were thrown by one of the Latin Kings, not the audience member.

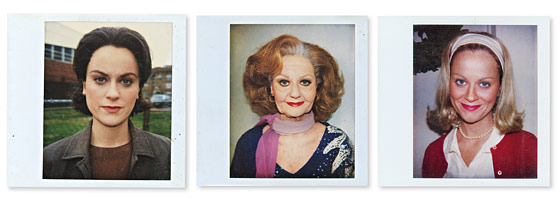

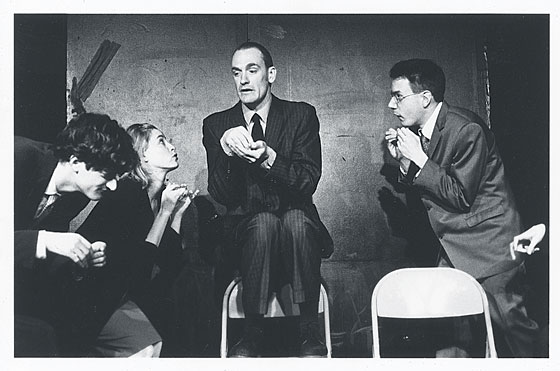

Makeup tests from Comedy Central's Upright Citizens Brigade TV show, 1998-2000.Photo: Courtesy of UCB

In 1995, McKay moved to New York to take a writing job on Saturday Night Live. Rather than disband, the UCB brought in Amy Poehler, who’d performed with Chicago’s Second City troupe with Tina Fey and Rachel Dratch. Within a year, the UCB group also felt the pull of New York, where they hoped to find a bigger audience and showbiz visibility.

AMY POEHLER: I moved to Chicago right after I graduated from college, in 1993. Just to set the scene for you, Chicago, like a lot of cities, was in an early-nineties depression. A lot of flannel, a lot of good music, a lot of bad politics.

BESSER: Right away, everybody saw how talented she was.

SETH MEYERS, SNL: They were all sort of exceptional. Besser was doing stuff that was aggressive and unique—he was a guy that everybody talked about in reverent tones. Ian is one of the purest improvisers, as far as never being out of the scene. Whereas Walsh always seemed a little out of the scene, in a way that let the audience know how much fun he was having. And Poehler was probably the most feminine and most masculine performer. Masculinity—that’s probably not the right word. She’s an alpha performer. I think that’s ingrained in her, but it got trained very well, being with those other three guys.

RICHTER: In the comedy world, a woman that strong and funny is worth ten funny guys.

POEHLER: Besser has been, in many ways, the captain that pulled us along. He always had really big thoughts of what UCB could become, long before any of us actually did.

IAN ROBERTS: We wanted to get a TV show, and I remember the artistic director at Second City saying, “You’re making a big mistake. You’ve got a future here.” And we said, “Well, we’re gonna roll the dice. See ya.”

MATT WALSH: We knew we had to go to either New York or L.A. We had a little sit-down at [Chicago’s] Salt & Pepper Diner and decided New York was the better town to get a following.

POEHLER: [By then] Besser and I were dating, so it was easier for me and my boyfriend to go. But Ian had just gotten married, and Walsh was leaving his hometown. It felt very scary.

RACHEL DRATCH, SNL: I was like, “How could you leave? Are you crazy?” And then they [came] here, and took over the whole joint.

PART I: NEW YORK

The UCB Four arrived in New York in 1996 and quickly began putting up small shows at venues like Rebar and Luna Lounge, where the weekly show “Eating It” was becoming the city’s must-see comedy showcase.

DAVE BECKY, co-founder, “Eating It”: There was this room in L.A., the Un-Cabaret, where all the brilliant comedians used to go up and not do their acts—they’d go and tell stories and try new stuff. And there was nothing like that in New York.

PETER PRINCIPATO, UCB agent, 1996–97: [Comics] were still making development deals for seven minutes of stand-up, because [networks] were still trying to re-create the Roseanne–Tim Allen–Bill Cosby sort of thing. Nobody knew how to put together, or label, or sell, alternative comedy.

POEHLER: I [recently found] a running order from the Luna Lounge in 1996: Janeane Garofalo, the State, UCB, Marc Maron, and Louis C.K. I remember being so excited every week to do our bit.

JANEANE GAROFALO, actress: I met Amy shortly after they moved here—through a book club, believe it or not. I liked her immediately but also remember thinking she was a kid—she’s very tiny and looks very young. I thought she was just a very mature high-school student. I’m serious.

MICHAEL DELANEY, performer-teacher: It was a struggle for those guys at first. [They’d be] out on the street with a bullhorn all the time, creating some kind of ruckus.

ROBERTS: We had nights when we had four people in the audience. And those four people were people we’d handed flyers to in the park.

Within a few months, UCB had four regular shows running, including “ASSSSCAT 3000,” in which a guest would tell off-the-cuff stories that would then be used to create scenes. Early monologuists included Garofalo, Richter, and David Rakoff.

CONAN O’BRIEN: Improv had been really important in Chicago, and it had a toehold in Los Angeles, where you had Pee-wee Herman, Phil Hartman, Lisa Kudrow—all coming out of the Groundlings. But in New York in the early nineties, nobody was talking about improv.

DELANEY: There’s always been a stigma against it, because it’s so damn goofy. I mean, 90 percent of all art sucks, and 95 percent of all improv sucks.

PAUL SCHEER, co-founder, Human Giant: I was at NYU, doing short-form, Wayne Brady–style improv. I didn’t know there was anything else. And then, one weekend, my friend was like, “Dude, you gotta go check out this group.”

ROB CORDDRY, The Daily Show; Childrens Hospital: In 90 minutes, they changed how I felt and thought about comedy. It was punk rock—super dirty and loose.

ED HELMS, The Daily Show; The Hangover: They had the thing that drew me to comedy in the first place: that energy when somebody’s putting it all out there, acting like a massive jackass, with no reservations. It was something that scared the shit out of me, and therefore I had to try it.

O’BRIEN: One night they asked me to do the [“ASSSSCAT”] monologue, and I said, “What happens?” Because I’m a guy who likes to prepare. And they said, “Don’t prepare—just take a word from the audience, start talking, and see what happens.” So someone shouted out “Dog!” and I started telling this story about a night that I pissed my dad off because I refused to take the dog out, and how he blew up—how I could hear him running down the stairs to get me. I told it in this comedic way, and people were really laughing, but I realized that I had, like, a sense memory of this big conflict I’d had with my dad in 1979. It was actually therapeutic.

PART II: BUILDING

The UCB Four began teaching and holding shows at Solo Arts, a 40-seat, un-air-conditioned space in Chelsea. Students were versed in a philosophy known as “Yes, and …, ” in which one performer builds upon another’s idea, and learned a complex form of interconnected scenes called “the Harold.” Within a few years, members of Harold teams like the Swarm, Mother, and Respecto Montalban became small-stage celebrities.

SETH MORRIS, writer, FunnyOrDie.com: That first wave of classes was a real eye-opener. Everyone there was used to being the funniest person from wherever they came from.

DANIELLE SCHNEIDER, performer: There weren’t so many people then, so if you could stand up straight, you’d get on a team.

CHRIS GETHARD, performer-teacher: It was the island of misfit toys, man.

POEHLER: When you move to New York, you’re always looking for your tribe.

JACKIE CLARKE, performer-teacher: Early on, it was mostly men, maybe 70-30. The first class I took with a female teacher was with Amy Poehler, and I remember being like, “Oh, she laughs at different things. She gets it when I make a Judy Blume reference.” LENNON PARHAM, performer: A lot of women, we have this deference. Once that was out of me, I was attacking the stage.

In 1999, the group found its first permanent space, in the former Harmony burlesque club, a storefront on West 22nd Street with mirrored walls and a runway.

MORRIS: I found out years later the way it worked: Women would rent stage time that served as advertisement for their services. There was a house boom box, and each would play her own mix tape. The ladies would bring dudes up from the back and take the fire escape to the apartment directly above the theater, which had mattresses on the floor.

SCOT ARMSTRONG, writer, The Hangover Part II: We’d be performing, and old fat guys would walk in, confused and looking for naked girls.

DANNAH PHIRMAN, performer-teacher: I shouldn’t say this, because I’m Jewish and I don’t want to give us a bad rap, but a lot of them were married Hasidic Jews.

SCHEER: There were all these crazy, experimental shows going up. Matt Walsh did [one] called “Robot TV” that was for robots, by robots; we were only activated by the word “Landau,” like Martin Landau. There was a Halloween show called “Killgore,” where we would wrap the entire theater in clear plastic wrap and put on, like, the bloodiest comedy show ever.

ROB HUEBEL, Childrens Hospital; co-founder, Human Giant: We would go down to Union Square or Washington Square Park and stand there putting flyers in people’s hands. Once, around Christmastime, we had one of our guys, Owen Burke, dress up as Santa Claus. We were yelling to pedestrians, “Step right up, and take a swing at Santa Claus,” and then handing people a roll of wrapping paper. But in New York, that’s a terrible idea, because people just wanted to beat the shit out of Santa Claus.

OWEN BURKE, FunnyOrDie.com: You don’t think it’s going to hurt, but when you have the paper on there, and a kid whips it against your neck, you’re like, “God damn!”

BRETT GELMAN, The Other Guys: There was this trapdoor in the box office, and you’d go down to a sandy floor underneath the theater, where we’d all be drinking Jack Daniel’s and smoking weed.

JULIE KLAUSNER, author, I Don’t Care About Your Band: So much pot. More than you could ever understand. I tried improv stoned once, and I had a panic attack and a fight with my boyfriend after. It did not go well. Never do it.

RICHTER: People don’t take improv classes just to get onstage and be funny; it’s to get fucked up with funny people. You gotta have openness in your schedule. And all this openness is going to keep you open to things like, “Drink this. Smoke this. Try this pill.”

JAKE FOGELNEST, host, Squirt TV: To sign up for classes, you would drop off a $25 deposit. So there were all these deposits that never got put in the bank—just a bunch of checks and cash and shit, in a box in the basement. It was really disorganized.

ROBERTS: The “business” was me keeping track [of payments] on the fridge.

WALSH: The classes have always paid the rent. And the shows were a loss, frankly, for the first few years.

The UCB Four started to make a little money with a (non-improvised) TV sketch show, Upright Citizens Brigade, which aired on Comedy Central from 1998 to 2000. As it was being shot, Besser and Poehler broke up, and the group struggled with the responsibilities of being a collective and the lure of individual stardom.

RICHTER: At a certain point, there became a strong pull to get [Poehler] away from the rest.

POEHLER: Some of us had opportunities to make money [by] splitting up the group. We fought that off for a while. Every once in a while, a sitcom would come up, and I didn’t torture myself by putting myself in the position to get things and then have to turn them down.

ROBERTS: [Matt and Amy] handled [their romantic breakup] so well. Matt called me up and said, “Hey, can I come over?” And I thought it was to use my printer. So I said, “Yeah, I may not be here, but I’ll leave the door open.” He was like, “No, dude, I wanna talk to you.” And he sat down and said, “Look, Amy and I broke up, and we discussed it, and it’s not going to have any effect on the group.” And we never missed a beat.

PART III: COMMUNITY

As the UCB business began to grow, so did the accompanying social scene. The students frequently gathered (and still do) at the Peter McManus Cafe, a cop bar on Seventh Avenue at 19th Street.

“I’ve seen things most people will go to their graves never even imagining.”— Adam Pally

KLAUSNER: You’re asking about my twenties, which is a Venn diagram of bad decisions and decisions made at McManus. Which were generally the same thing.

HELMS: A comedy community is comprised of a lot of people who have not thrived in conventional social circles. And that just makes for a giant pool of awkward sexuality.

BOBBY MOYNIHAN, SNL: Every single female I’ve ever worked with at UCB, I fell in love with for at least fifteen minutes after she told an amazing joke onstage.

CASEY WILSON, SNL: Right off the bat, my instinct was, “Look at all these guys who are all comedy-hot.”

TARA COPELAND, performer-teacher: [A lot of the guys] were rejected in high school and maybe college. But I thought they were hilarious and charismatic and cute, and we were all always together.

ADAM PALLY, Happy Endings: I remember seeing Ellie [Kemper], because she’s the nicest person, getting trapped and literally having to make her way from nerd to nerd to nerd to get out of the theater.

ELLIE KEMPER, The Office: [Laughs] Oh, I don’t know … That’s very nice of him.

ZACH WOODS, The Office: I didn’t feel like the object of a lot of positive sexual attention. No one was especially eager to be hooking up with an awkward, backne’d 16-year-old with a praying-mantis body. Which is probably for the best, because it would have been illegal.

JESSICA ST. CLAIR, performer: A lot of comedy nerds met their comedy princesses.

JOHN LUTZ, 30 Rock: I met my wife backstage.

SUE GALLOWAY, 30 Rock: I saw John in a show and thought, “I have a crush on that guy,” which I guess is what guys who perform comedy hope women are saying.

PHIRMAN: I’m sure you can imagine 23 improvisers in a room together. I don’t think anyone had a real conversation about anything. We’d constantly do bits.

FOGELNEST: One night, Michael Stipe was hanging out at McManus with me, Horatio [Sanz], and Jimmy Fallon, and Horatio pretended to have a heart attack, very convincingly. Everybody knows this is just some asshole McManus bit, but Michael Stipe had no idea. He was mortified. It wasn’t always fun for people who weren’t in the theater.

SANZ: I don’t mean to sound like Sid Vicious or anything, but there are a lot of those nights I don’t remember. I do remember, one night, I threw a stool at this jukebox. Kurt Cobain was playing, and I thought that he would like that. Afterward, I called [the bar] very sheepishly and was like, “Sorry. I want to pay for that jukebox.” And the owner said, “Eh, don’t worry about it.” We pledged our undying support of his bar for life. I was given a key eventually.

In the fall of 2002, the UCB Theater faced two setbacks: First, Farahnakian and Diaz struck out on their own, opening the competing Peoples Improv Theater. (Diaz would later found a third competitor, the Magnet.) Then, in November, UCB’s building was shut down for a fire-code violation.

CHARLIE TODD, founder, Improv Everywhere: When I was in college, my house burned down. I would actually say that the UCB theater being closed was more tragic than that.

POEHLER: I was so bereft: “Oh my God. We’re never going to find another home.” There were months where we were performing around New York, asking people to hold on while we found a space.

ANTHONY KING, artistic director, 2005–2011: The real panic was, “Has this all been for nothing?”

ROB RIGGLE, The Daily Show; SNL: Maybe I was being naive and optimistic, but I felt like the community was so strong that we’d find a way.

Eventually, the group leased a 150-seat theater on West 26th Street, below a Gristedes.

JACK MCBRAYER, 30 Rock: It was a huge deal when we finally got that basement, where blood would drip from the deli above us. There were Hefty bags full of disgusting shit-water. We started calling them shit bags.

TODD: I was in a show where one of those bags burst, and somebody initiated a scene that was at a child’s birthday party with a Slip ’N Slide. We all slid on it. It was disgusting, and the audience was grossed out but loved it.

JENNY SLATE, SNL: The audiences are always hoping for a zoo, for the most energetic, weird, original thing they can get.

KEMPER: [In one scene], we were all on the ground, and I was laughing so hard, I wet my pants. And my teammate was dragging me across the stage, and there was a streak. I don’t know if anyone saw it.

ST. CLAIR: I’ve seen almost every man naked at one time or another. They love to take their balls out onstage.

MCBRAYER: Someone either [once] got teabagged, or was centimeters from getting teabagged, on the face. I’m talking about balls, fleshy balls. Strangely enough, it worked in the context of the scene.

PALLY: I co-hosted a show called “The Dirtiest Sketch Show.” It’s the one night where you are lauded for doing the most vile, offensive, racist, disgusting sketch you can do. I’ve seen things most people will go to their graves never even imagining.

KING: Two guys bought some dead chickens in Chinatown and fucked them onstage.

KLAUSNER: I heard about the one where Brett Gelman tap-danced in blackface.

GELMAN: It was Valentine’s Day 2004, and I had just broken up with my girlfriend, so I was pretty angry. Somebody came on the mike and said, “Ladies and gentlemen, September 10, 2001.” And the spotlight comes up and “The Candy Man” starts playing, and I come out naked in tap shoes and blackface, dancing horribly. Then all of a sudden, the lights turn red, and [the German industrial band] Rammstein comes on, and I look at the audience and I go, “Tomorrow, a terrible tragedy will happen that will kill thousands of people. America will become a cage of fear. What are you going to do when fascism takes over?” And I started goose-stepping around the stage. Then, after about a minute of that, “The Candy Man” comes back on, and I finish up the tap dance. And I received a standing ovation.

PART IV: HIGH-STATUS CHARACTERS

The theater’s regulars had begun to join the cast of Saturday Night Live: Sanz in 1998, Poehler in 2001. The Daily Show hired Helms, Corddry, and Riggle. MTV gave the Human Giant troupe a show. UCB was becoming a gateway to bigger things.

GELMAN: When Lorne Michaels started pulling people from the theater, there was an increased sense of competition.

WILSON: As fun as [UCB] was, it attracted people that had the eye of the tiger.

WILL HINES, performer-teacher: People go through a pretty predictable arc of finding the UCB, falling in love with it, and immersing themselves for a year and a half. Then there’s another year where they’re kind of ripened and not yet bitter, and if they don’t get put on a team by the end of that year, they’ll [eventually] become resentful and leave.

KEVIN MULLANEY, performer–UCB school manager, 1999–2006: The people that have succeeded are almost entirely the people you’d see at the theater at 10 a.m. on a Thursday, trying to work out a sketch or a show.

KING: Aziz [Ansari] and Scheer were always doing new things.

SCHEER: [Our group] Human Giant was totally built by UCB. Aziz was like, “I don’t want to host just stand-up.” So Aziz and I did a full-on experiment, where we went to the Scientology center in midtown, spent a day there, and reported our findings.

AZIZ ANSARI, Parks and Recreation: Paul, at the time, was on Best Week Ever, so [the Scientologists] recognized him and pulled him into a different area, and I was trapped with this weird dude. I think I gave them the name of some Indian kid I went to high school with. And we talked about it in the show that night, which was fun, because that’s the kind of thing you can’t really do at a comedy club.

SCHEER: Chevy Chase came by one time and did the monologues.

HUEBEL: This was around the time when Amy was still on SNL, and I think Chevy wanted to get back involved with the show—trying to get to know the young guys—so he was coming around the theater. I came in, and Chevy was backstage. Just to preface it, I grew up the biggest Chevy Chase fan in the world. I knew every word to Fletch and Caddyshack. I wanted to be Chevy Chase. So we go into a little spot just off the lip of the stage, and there was a break in the conversation, so I said, “Chevy, I just want to introduce myself. I’m Rob Huebel.” And he just slapped me across the face. He didn’t say anything; he just looked at me for a second and belted me. It was really hard—offensively hard.

JASON MANTZOUKAS, performer: I wouldn’t know exactly how to explain it to you, other than to say it was simultaneously amazing and terrible.

HUEBEL: He tried to make a joke afterward, something to the effect of, “Don’t interrupt me when I’m talking, ha ha ha.” And I just stood there. They brought us all on, and it was awkward. But in his defense, he wasn’t trying to be mean; he was trying to be funny. It was a bummer only because I was such a huge fan.

MANTZOUKAS: That being said, backstage in the green room, hanging out, he could not have been a lovelier guy.

CHEVY CHASE: It’s a faint memory, but I know it was done in good humor.

EPILOGUE: IMPROV EVERYWHERE

In 2005, the UCB opened a theater in West Hollywood that quickly became populated by UCB alumni who had gone to L.A. for work on such shows as Community, Parks and Recreation, and Childrens Hospital. The New York hub has grown to include two theaters, a training center, five touring troupes, and eight Harold teams. About 8,000 students are taking classes this year, on both coasts. On any given night, you can find a group flailing around the 26th Street basement, exposing their strangest comedic impulses (or worse).

GETHARD: It’s hard. Most of my best friends live 3,000 miles away.

DELANEY: When all your colleagues up and leave, it’s a huge bummer. [But] it does make room for new blood. It’s a built-in graduation system.

MOYNIHAN: Every single one of the people on my first Harold team is now working in television. I just got an e-mail about a job, and one of my old students wrote the script. Thank God I was nice to that guy.

CORDDRY: Megan Mullally—who’s on my show, Childrens Hospital—is consistently startled by how supportive the current comedy community is. And it’s largely to do with the UCB. The way they teach improv is to support your partner. If your partner looks good, you will look good by proxy.

GAROFALO: It’s a very democratic, very openhearted approach to group comedy. It’s a positive thing for any of the people that get involved in it, because you can apply that to your life.

ARMSTRONG: The UCB now is what the Second City was in 1980: If you make it there, you’re probably pretty good.

RICHTER: For the next 20, 30, 40 years in this country, the comedy that we will be purchasing as consumers will have some UCB on it.

JON GLASER, writer, Late Night With Conan O’Brien: I went and did [“ASSSSCAT”] a few [months] ago, and Matt Damon showed up.

DELANEY: The sketch-and-improv scene when I came to New York twenty years ago was anemic. Now it’s actually bloated.

POEHLER: Moving to New York and trying to get a show—oh my God, we were naive. But the great thing about taking big chances when you’re younger is you have less to lose, and you don’t know as much. So you take big swings.

See Also

Slideshow: Amy Poehler as 30 Different UCB Alter Egos

Poehler and Matt Besser onstage, 2000. Photo: Jason Spiro

Will Berson, Jamie Denbo, Seth Morris, and John Bowie. Photo: Jason Spiro

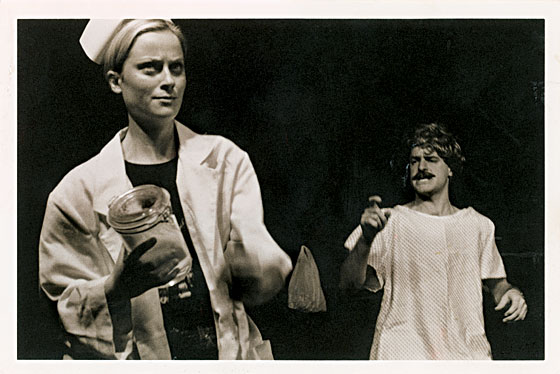

Amy Poehler and Horatio Sanz, 2001. Photo: Jason Spiro

Tina Fey and Rachel Dratch, 2001. Photo: Jason Spiro

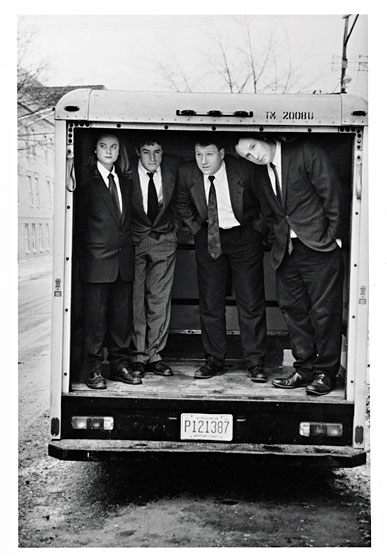

Poehler, Matt Besser, Ian Roberts, and Matt Walsh, 1995. Photo: Courtesy of UCB

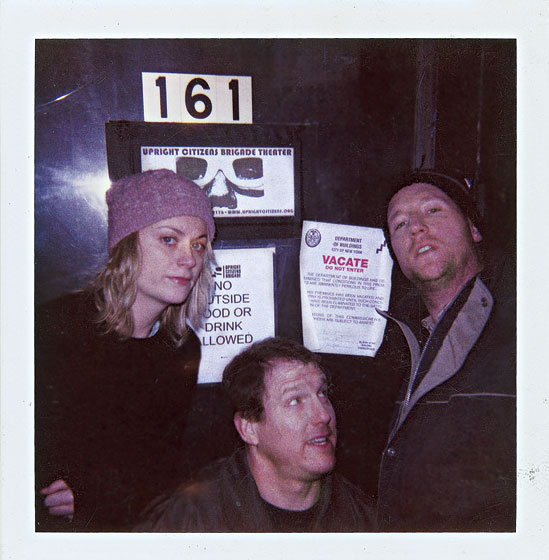

At the closed-down 22nd Street theater, 2002. Photo: Courtesy of UCB

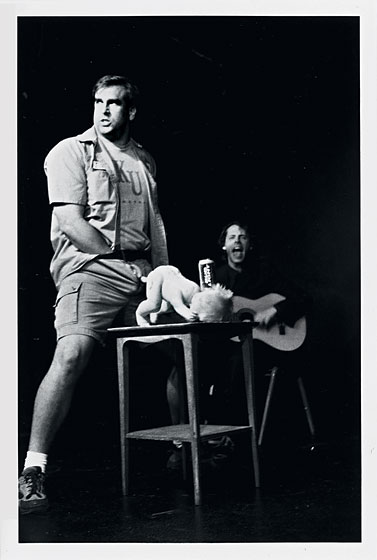

Poehler, Besser, and Walsh in “That’s F’d Up!,” 2000.Photo: Jason Spiro