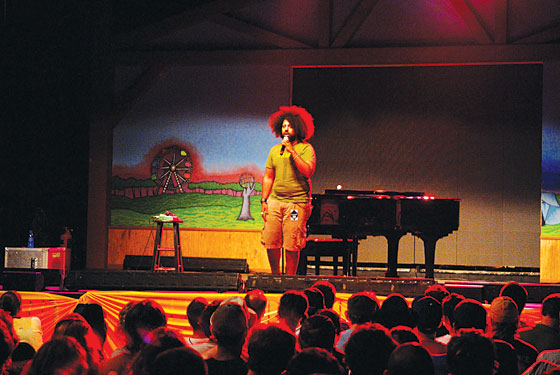

Of all the challenges Conan O’Brien faces on his nationwide “Legally Prohibited From Being Funny on Television” tour (translating his talk-show aesthetic into a live comedy performance; avoiding coming off as a sore loser), the biggest challenge might be self-inflicted: having to step onstage every night in the wake of his opening act, Reggie Watts. Watts, a star of New York’s alt-comedy scene, is the kind of comedian who tends to close shows. His sets are loud, disorienting bouts of improvised anti-comedy. He is, in many ways, the opposite of O’Brien, as both a performer and a being. O’Brien is gangly and pale; Watts is chubby and dark. O’Brien has an ironic post–Tonight Show beard and that signature little flip of orange hair; Watts has a huge asymmetrical Afro that blends into a beard as thick and dark as good-quality garden loam. O’Brien approaches comedy, famously, as a writer, spending hours preparing each moment onstage. Watts improvises his act so thoroughly that, if a hard-core fan were ever to request a favorite old bit, Watts would probably have no idea what he was talking about. Over the past seventeen years, Conan has established himself as one of America’s most stable comic voices. Watts builds his comedy out of radical instability: He switches so fluidly among different accents and personae (soprano, baritone, Californian, Cockney) that it’s hard to tell what the real person even sounds like. Conan, in other words, is a recognizable type of comedian: a subspecies of the genus Letterman. Watts is like a character Conan might have invented—half-man, half-astral-funk Muppet.

Their partnership, however, is neatly symbiotic. Watts lends Conan underground credibility while Conan gives Watts national exposure—he’s probably the highest-profile opening act in the country right now. And it seems to be working out. Through its first month and a half, Conan’s tour has drawn rave reviews, and Watts has inspired thousands of delightedly surprised testimonials on YouTube and Twitter. He embodies the paradox of the cult star: a charismatic, powerfully original performer who probably deserves to be super-famous but whose originality disqualifies him from all the usual channels of super-fame. A fellow comedian recently called him “Black Galifianakis,” mainly because of his beard, but the affinity goes deeper. Zach Galifianakis was also an anti-comedian revered among Brooklynites before he broke out nationally as a star of The Hangover and a host of Saturday Night Live. As the Conan tour nears its end (it hits Radio City Music Hall this week and finishes June 14 in Atlanta), we might be witnessing the birth of Reggie Watts as a national phenomenon: Galifianakis 2010.

I first saw Watts perform last March at MoMA—an unusual comedy venue, but appropriate for someone who pushes so hard against the traditional limits of the form. He was headlining a variety show in one of the museum’s small subterranean theaters, and his twenty-minute set contained as much variety as the rest of the acts combined. Its opening was unpromising: Watts walked onstage in a tight red T-shirt and suspenders and started bumbling, in a refined British accent that I took to be his natural speaking voice, through some awkward small talk. “We’ve come quite a bit of the way here already,” he said, “and we’re just getting started.” He paused. “It’s one of those years, you know? And, uh, I think a lot of us can feel—and agree—to most everything that we’re here, within ourselves, this evening … ” It took a few sentences to figure out that this aimlessness was, in fact, the performance itself. He was building, phrase by phrase, a structure of deliberately failed logic, with each piece related just enough to follow the last but not quite enough to make sense with the whole. It was gourmet word salad—a brilliantly sustained comedy filibuster. Gradually the crowd adjusted, and Watts’s pauses filled with increasing laughter. “We, more than any other time,” he continued, “and I mean this when I say this—more than any other time, we’ve been here, right now. You know?” He spoke, haltingly, about polycarbonates and the landfill system, cited fake authorities (“French and Saunders once said … ”), referred to the MoMA as the Whitney, and snuck in, out of nowhere, a near-perfect impression of Bill Cosby. Occasionally, with a straight face, he’d substitute a bizarre series of noises for a word, or his voice would cut in and out while his mouth kept moving, so it looked like the microphone was malfunctioning. It was like a seminar on public speaking gone wrong. Soon the crowd had fully acclimated, and Watts was officially killing.

The absurd monologuing was an act in itself, and most comedians would have stopped there. But Watts took things to another level. Several times during the set he broke into music—creating songs, layer by layer, using only his voice and a little machine called a loop pedal. He beat-boxed, hummed, clicked, sang, and rapped; he mixed rock, hip-hop, techno, opera, Broadway, church hymns, and soul. The nonsensical talking blended into the music, and the music blended back into the talking, with no connective thread other than that it all seemed to be emanating from the mouth hole at the approximate center of Watts’s wild halo of hair. He looked, at times, like someone suffering a seizure from an overflow of incompatible talents. By the end of his set, he was doing whatever is better than killing—double-homiciding, mass-murdering.

For the record, Watts’s natural speaking voice is pure neutral delocated middle-class American—a little higher than I expected, a little nasal. “I think that when people seek any form of self-education,” he told me, “their accent just kind of neutralizes. It gets closer to a newscaster.” We were speaking in his manager’s office in the Village, the week before he left on the Conan tour. He wore blue-and-red-striped suspenders, a gray T-shirt that read CREATIVE CAPITAL, and black jeans rolled up at the ankles. His mustache curled up inexplicably on one side. Each of his pinkie nails was long and painted—one pink, the other black.

I asked Watts how many different accents and personae he has. He said he’s not sure; it’s an unstable crew. But he estimated that he’s spent half his life speaking in a British accent, of which he has four or five main variations. Then, without prompting, he started to demonstrate them. (Talking with Watts is like watching a mellow version of his stage show.) There was an educated Londoner (“very kind of subtle”), a thick, sludgy working-class voice (“you’re trying to understand the properties of cheese, you want to put it on your biscuits”), a hyper Cockney (“let’s go out like for a pint or wha’ever, catch some o’ them birds, y’know what I mean, we could talk forevah about these birds”). He also has what he calls “European in general,” plus deliberately terrible Irish and Australian accents, sci-fi robots, a range of feminine voices, and a whole crowd of Americans: New Jersey cabbies, effeminate southern men, his grandfather from Cleveland. “They just kind of pop into my head,” he said. “It just happens. Sometimes I’ll be channeling a voice that I heard on the subway. Some of it’s just based on types of people, lifestyles. I don’t really practice at all. I’m always riffing throughout the day, cracking jokes with friends. I kind of fall into it.”

Suddenly he started speaking like a West Coast Wiccan girl, in a voice that oozed patchouli and druid crystals. “You know like the spirit world is so crazy?” he said. “Because Gaia is like a full-being sentience? And we are the stewards of it? And Shilanqua was talking to me yesterday about the burn and our responsibilities to clean up after we’ve been in camp? And base camp was 30 feet away and Trinity was like, ‘How come you didn’t bother to come to the morning temple ritual?’ ” And on and on and on and on.

Reggie Watts’s childhood seems to have been engineered to produce a comedian exactly like Reggie Watts. He was born in Germany, in 1972, to a French mother and an African-American father. His mother spoke little English, so Watts grew up fluent in French. By age 4 he’d also lived in Spain and Italy—his dad was in the Army—which means his brain’s language centers got exposed, at a crucial period, to most of the accents of Europe. (Onstage, he’ll occasionally launch into braided streams of French, Spanish, German, and Italian.) He spent the rest of his childhood in Great Falls, Montana, a place that must have seemed exotic in its mundanity. At 5 he started studying classical piano, adding yet another language—music—to his repertoire. (He studied jazz in college, and has played with several rock bands, opening for Regina Spektor, Dave Matthews Band, and the Rolling Stones.)

Because of his childhood culture-hopping, Watts says, he grew up with anthropological tendencies. He didn’t so much inhabit the world as study it. “I always tried to find the causality of why things are the way they are,” he told me. At home he’d take his toys apart. At school he’d invent backstories to explain why bullies were so mean, or he’d drive his teachers crazy by interrogating them about why they had become teachers. He became a connoisseur of what he calls “in-between” moments—times when he was immersed in a situation but could also see it from the outside. Despite his familiarity with music, for example, he found himself looking around in wonder during school orchestra practice. “Here I am in second violin section—the conductor getting up and tapping the baton,” he said. “And all these people with horsehaired wooden sticks and strings, looking at a bunch of symbols on a piece of paper. And the bass players are tall and look like their instruments, and the cellists have long hair and look like cellists. I’m sitting there like, What is this?”

Watts always felt not of this world. “For most of my life I’ve liked to pretend I live in a starship. Punching in fake codes to get into doorways that obviously are not secure.” (He makes some sci-fi door noises: Bee do do deep. Psshhhh.) “I love that idea of living on a spaceship. Because essentially we are: a gigantic thing floating in some infinite darkness that’s running on principles that we don’t even understand.”

Onstage, Watts likes to make fun of observational comedy. He’ll slip into a low, drawling, American voice and say things like: “Women be crazy … Now here’s a scenario. A woman be, like, sittin’ down in the chair and shit? You know what I’m saying? And she might, like, get up at some point, you know? And walk out a door and some shit?” Long pause. “Know what I’m sayin’? That’s fucked up.”

But Watts’s own comedy is actually—in a unique way—hyperobservational. He notices things, the more trivial the better, and plays them for improbable laughs. It’s less a stand-up act than a public report on his decades-long ethnographic study of human behavior. “I like talking about mechanisms,” he told me. “Because it’s kind of absurd. It’s not trying to be noticed, it’s trying to be transparent.” He wrings a lot of humor, for instance, out of the way performers adjust their microphones. He’ll pick one up and start untwirling the cord from the mike stand, and then he’ll keep doing it for twenty seconds, exaggerating the motion until it turns into its own little dance. Or he’ll sit at a piano and, before singing, fall into an almost Chaplinesque struggle with his mike stand’s tension knobs. He recently got onstage after a string of more-traditional stand-up comedians and performed a silent set—moving his lips, mimicking the gestures and rhythms of stand-up, even pausing between silent jokes to wait for the crowd to laugh.

Compared to his topical contemporaries’, Watts’s comedy can seem purely absurd, derived from the world but not of the world. It’s like Richard Pryor with the human content surgically extracted. But Watts’s nonsense actually makes a strange kind of social sense; his incongruity is congruent with the development of American culture over the past ten years. It’s comedy for the Internet era: this infinite fracture that forces us to be fluent in a million discourses, and to speak them one on top of another. Watts parodies that, dropping us in and out of discussions already in progress, never relating or resolving them—showing us all what we’ve done to logic, and how silly it is. He treats knowledge wiki style, feeding the audience false information, as when he recently told a crowd in Seattle that the Space Needle was built in 1993. He assumes a ridiculous intimacy with audiences, talking to them as if they’ve grown up with him: “Do you guys remember when we went on that field trip … Remember when Brian got in trouble?”

Watts described his method to me as “culture sampling.” He picks templates, he says—a scientific lecture, a corporate report, hipster gossip—and then fills them out, off the top of his head, like Mad Libs. When I asked if he’d ever considered writing material in advance, he basically recoiled. “No. That would suck.” He talks about the process of improv in quasi-mystical terms, as a kind of spiritual jazz—a way to honor the world through mindfulness. All his ideas come, he says, from being alert to his environment and opening his mind to something he refers to as “the Source.”

“Improvising music has helped me a lot,” he said. “Music is very similar to comedy: It’s all about texture, timing, context, vocabulary, performance. When someone’s onstage doing a solo, essentially it’s the same thing as what a comedian does. They’re in the moment. They’re listening. The environment is giving you stuff constantly: a woman yelling something, an animal making a weird sound in the forest, a window being rolled up, static on a radio. Someone turns to you and says something in the same key as the radio. If you pay attention to the world, it’s an amazing place. If you don’t, it’s whatever you think it is.” As the world will presumably discover, now that it’s beginning to pay attention to Reggie Watts.