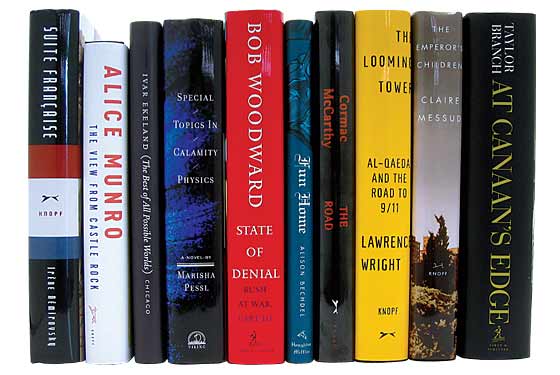

10. ‘The Emperor’s Children,’ By Claire Messud

This book should send a chill down the spine of anyone who has ever attended a certain kind of New York party: where seduction is indistinguishable from networking, and a few smirking observers spill poison into one another’s ears. And whereas many novels of New York manners get the tone wrong—they are too arch, too superficial—Messud’s is a genuinely icy concoction, an amused, insightful condemnation of a youthful media elite who (to quote Sondheim) career from career to career. Let the striver beware.

9. ‘Special Topics in Calamity Physics,’ By Marisha Pessl

A first-time novelist’s mission is to forge something new out of her influences. Clifford Chase and Olga Grushin did that this year with, respectively, Winkie and The Dream Life of Sukhanov—yet neither book rivaled Pessl’s debut in scope or detail. Yes, Nabokov is here, in a teenage girl’s butterfly collection, in her erudite but sinister professor-father, in the plot’s hairpin turns. But the central mystery, structured as a Great Books course that ends with a multiple-choice test, contains glorious conceits entirely Pessl’s own.

8. ‘The Best of All Possible Worlds: Mathematics and Destiny,’ By Ivar Ekeland

Leave it to a Latin Quarter intellectual to locate a single “totalizing” idea behind four centuries of scientific, political, ethical, and technological progress. The intellectual is Ivar Ekeland—mathematician, philosopher, and former president of the University of Paris-Dauphine. The idea, originally thought to have come straight from the mind of God, is called the “principle of least action.” Its meaning is as pleasant as it sounds: Nature always achieves its ends with minimal effort. In less than 200 pages, Ekeland explains how this insight became the mathematical key to finding “the best of all possible worlds.” For a French theorist, he writes prose that is shockingly clear, which is perhaps why he exiled himself to western Canada.

7. ‘Fun Home,’ By Alison Bechdel

Each year, one graphic novelist gets crowned “the next Art Spiegelman.” And you don’t read his book, because it actually seems kind of boring. Don’t make that mistake with Bechdel. One of the best memoirs of the decade, Fun Home tells the story of her closeted father, pairing visuals and storytelling in a way that is at once hypercontrolled and utterly intimate.

6. ‘At Canaan’s Edge,’ By Taylor Branch

After more than twenty years of Freedom of Information requests, Branch concludes his history of “America in the King Years” with this chronicle of Martin Luther King Jr.’s final days. Unlike the hagiographers, Branch never shies from acknowledging King’s complexities and compromises—and it’s that honesty that makes his tribute to the man’s world-changing optimism far more powerful than, say, the can’t-we-all-just-get-along pablum of Bobby.

5. ‘Suite Française,’ By Irène Némirovsky

This year’s best historical fiction was once impossibly contemporary. In 1940, a Jewish writer who fled Paris set out to write a five-part, thousand-page novel. She finished two sections—one about a village sliding toward collaboration—before being sent to Auschwitz in 1942. We gather from Némirovsky’s journals that her next novella would have grandly raised the stakes on its characters. What a painful testament to her truncated life: a masterpiece that ends midstream.

4. ‘State of Denial,’ By Bob Woodward

It wasn’t until this fall that the smoke of 9/11 finally cleared and many Americans figured out where their country was—which was lost. But how had it happened? State of Denial provided the most powerful, if not the most artful, explanation. To many who opposed the war, of course, the book’s revelations (Bush played fart jokes on Karl Rove, the White House lied about that mission-accomplished banner) were not exactly shocking. But the fact that Woodward, the voice of the political Establishment, was reporting it (it took him three books to get it right) made it safe for all of Washington to follow in his wake. It was, finally, an accountability moment.

3. ‘The View from Castle Rock,’ By Alice Munro

In her distinctive, spare voice, Munro has fictionalized slices of her family lore, going back to her Scots ancestors’ migration to rural Canada and rolling right up to her own late adulthood. What feels fresh and new about the book, though, is that—even when she’s writing in the first person—she almost seems to have stepped away and let the stories embroider themselves.

2. ‘The Looming Tower,’ By Lawrence Wright

Among blustery, heat-of-the-moment exposés like The One Percent Doctrine and wish-I-had-time-to-read-that blow-by-blows like Fiasco came this brilliantly told epic about the rise of Al Qaeda—in which Osama bin Laden himself comes off as a pissy dilettante who stumbled into history (it is his number two, Ayman al-Zawahiri, who emerges as the brains of the organization). We had no right to expect a book of such depth and balance just five years after 9/11. Years from now, historians will still be trying to top it.

1. ‘The Road,’ By Cormac McCarthy

McCarthy’s last two books have been lamentations for lost worlds. In No Country for Old Men, he mourned the disappearance of morality, while in The Road he mourns the disappearance of, well, everything, creating a postapocalyptic novel that successfully marries Beckett with Mad Max. It’s both a serious meditation on the purpose of life and the best end-of-the-world horror flick you’ve ever seen.

Honorable Mentions

Daughters of famous writers Kiran Desai (The Inheritance of Loss) and Lisa Fugard (Skinner’s Drift) proved they could hold their own. The creative Internet ad for Grégoire Bouillier’s The Mystery Guest nudged publishing into the YouTube age. George Saunders and Adrian Nicole LeBlanc got well-deserved MacArthur “genius” grants. Allegra Goodman’s Intuition was the best science-fiction book of the year (as in fiction about scientists). David Mitchell (Cloud Atlas) went intimate and autobiographica in Black Swan Green. William Styron’s death reminded us of his gutsy, deeply moral novels. Ian Buruma’s Murder in Amsterdam demonstrated how Europe’s relationship with its Muslims is even more critical than our own. Fledgling Europa Editions brought classy but edgy European fiction to America (Amazing Disgrace, Old Filth). Peter Carey savaged the go-go art market in Theft.

Richard Powers got his due, winning a National Book Award for his ninth novel, The Echo Maker. In Absurdistan, Gary Shteyngart did funny-sad as only a Russian could. The Wild West anarchist-revenge tale at the heart of Thomas Pynchon’s Against the Day—cut out the other 600 pages and you’ve got the best novel of the year. Peter Hessler’s Oracle Bones captured China on the brink of a prosperous, uncertain future. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (Half of a Yellow Sun) and Dave Eggers (What Is the What) wrote brilliantly of Africa for a new generation.

Industry Star: Jonathan Burnham

With Miramax Books in turmoil in 2005, it surprised no one that founding publisher Jonathan Burnham decided to go his own way. But most expected him to spin off one of those personality-based imprints (like Jonathan Karp’s Warner Twelve). Instead he became publisher of the flagship division at HarperCollins, a many-tentacled behemoth better known for celebrity tell-alls than high literature. So what’s he doing under the same Murdochian tent as Judith Regan? Making Harper more respectable, for one thing. “I think they wanted to build on its strength—serious nonfiction—and to build the upmarket fiction list as well,” he says. To that end, Burnham has won some heated auctions—notably for a couple of thousand-page tomes you won’t be seeing at Wal-Mart: Vikram Chandra’s Indian-gangster epic Sacred Games and Jonathan Littell’s Les Bienveillantes, the first book by an American to win France’s Prix Goncourt. And sure, there are the celebrity bios, but two of this year’s successes were by Anderson Cooper and Madeleine Albright—not exactly O.J. HarperCollins has been diverting tons of money into new technologies, but one of its smartest acquisitions may have been Burnham. —Boris Kachka

Stinker

To paraphrase the breathless jacket copy, sometimes a book arrives with so much marketing and so many overblown comparisons, it’s bound to disappoint. Publishers wagered $800,000 advances on two lurid Victorian thrillers with highbrow yearnings—Jed Rubenfeld’s Freud-and-S&M mystery The Interpretation of Murder and Michael Cox’s verbose The Meaning of Night. Their titles told the “Da Vinci Code with a brain” promo story: Take a darkly evocative noun (murder, night), then add a patina of literary introspection that flatters readers (interpretation, meaning), and watch the hardcovers fly off the tables. Not this year.

Christopher Bonanos, Logan Hill, Jim Holt, John Homans, Boris Kachka, Hugo Lindgren, Emily Nussbaum, Adam Sternbergh