For a while now, the most remarkable thing about pop has been how pop it is. I realize that reads a bit like marveling at how it gets bright when the sun’s out, but bear with me. Remember how, for stretches of the past decade, the story was that record sales were collapsing, audiences fragmenting, the mainstream shrinking? How the pop charts were just one niche among many, filled mostly with great R&B and hip-hop from acts you wouldn’t expect grandparents to have heard about on TV? Lately those charts have circled back to a glitzy old model of a mainstream that anyone would recognize as “pop”—youthful, synthetic, danceable, high-wattage, fashion-obsessed, tabloid-covered, suggestive, whiter-than-it-used-to-be, shopping-mall, raised-on-Disney, popular pop.

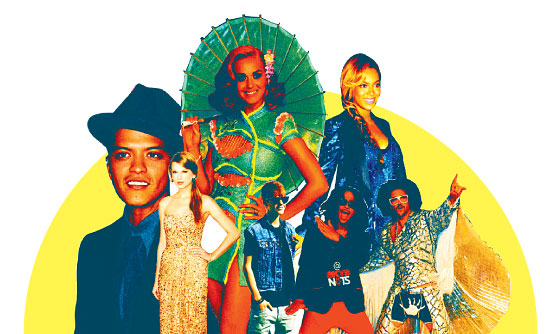

As a thought experiment, just imagine a snob from the eighties—the kind who complains about pop being “manufactured” and insipid—emerging from a coma last fall and getting a job at Billboard. This person wouldn’t fear for the genre or its glamour. He’d notice that everyone’s heard of Lady Gaga, a pop star in a classic sense: She makes dance music, wears weird things people talk about, questions sexual mores, and has public intellectuals writing about her cultural import. (As they once did with Madonna, but did not do, you’ll note, with Nelly or Ashanti earlier this century.) He’d notice the long chart dominance of Katy Perry, whose cheeky retronaut pop bears odd resemblances to the cheeky solo work of David Lee Roth. He’d see twinkly, wholesome Taylor Swift and cutie-pie crooner Bruno Mars—and that’s before getting to the actual tween demographic, the way huge numbers of adults know things about Justin Bieber and Selena Gomez. Most of all, he’d hear insistent dance numbers flooding in from everywhere—Flo Rida, Taio Cruz, David Guetta, reality stars who imagine they can sing. Trend-rider Rihanna is now all dance-pop, nearly all the time. It’s so much the sound of the moment that Britney Spears, or whoever makes Britney Spears do things, inevitably had to reenter the fray.

So many great glossy dance numbers! Much of this return to old-model glitz has been accomplished by mushing together two things Americans once found a bit over-the-top and embarrassing. One is club music, of the ecstatic global thump-thumping kind we’ve historically left to Europeans. The other, I suspect, is hair metal, with its full-color bombast and stadium excess, in which people will wear anything but pants, and the big themes are doing things all night long (partying, drinking, dancing, or otherwise). That combination describes a good share of recent charts—also, not coincidentally, Jersey Shore.

For much of the year, if you imagined the pop world as one giant high school, it looked oddly like we’d come back around to the cheerleaders and jocks taking the good lunchroom tables, preening and fist-pumping and glittering like vampires while others grumbled about how vapid they were. If you happen to be on my schedule, this was also the year during which those celebratory thumps and fireworks ceased to seem entirely awesome. The deluge of club numbers began to feel thin and perfunctory, and the new direction some stars are taking is the same path hair metal traveled—Gaga spent the year dwelling on eighties bombast, while Ke$ha took time off to work on an album with “cock-rock” influences.

But I get the feeling—and maybe you’ll agree—that pop’s sheer youthful popness has been a good thing for the vast majority of music that isn’t pop. Maybe it’s reassuring to have a lodestar to navigate around; maybe it clears space for people to focus on what can be invented at their own lunch tables. Some of the year’s best rap came not from people with sales aspirations, but youngsters and oddballs interested in tweaking hip-hop orthodoxy from the inside. Some of the year’s best indie rock came from artists chasing some underground vitality. Some great R&B came from artsy singers with not-so-mainstream ambitions. Maybe all the pop sets a good baseline—or reminds everyone else of what they were trying to accomplish that’s different.