Singer-songwriter Rosanne Cash, firstborn daughter of American legend Johnny Cash, has lived in New York for nineteen years and has been on Twitter for less than one. She tweets somewhere around 60 times per day, often weighing in on popular culture (she recently called Juno “a manipulative and contrived pile of shit”) and having fun with celebrities who might be taking themselves a bit too seriously. Last month, she made light of a certain actor’s role as online advice-giver: “Am eating coconut cake for breakfast. Will check Gwyneth Paltrow’s nutrition blog to see if that’s okay. After I finish eating it.” Then came a subconscious encounter with an action star: “Dreamed Tom Cruise tried to convert me to Scientology. I rebuffed him. Again.”

Cash logs on via iPad from the kitchen of her Chelsea townhouse or from her seat on a flight to the latest show. Her more than 6,000 Twitter followers have become familiar with the cast of characters in her life: the stalker who goes through her sidewalk recycling bin; her husband, musician John Leventhal, whom she calls “Mr. L.” and who sometimes irritates her with his loyalty to Steely Dan; her 11-year-old son, Jake, whom she occasionally refers to as “the Loan Shark” because he demands interest on the money he lends his forgetful mother; her stepdaughter and three daughters from her first marriage, to country-music hotshot Rodney Crowell; and then there are “the Twins,” a phrase Cash uses on Twitter for her breasts.

Cash, 55, likes to create amusing, clear-focused snapshots of her daily life. (“I asked Mr. L. what percentage of what I say he actually listens to and he said ‘probably at least double digits,’ ” she wrote recently.) But her mode isn’t always domestic comedy. In the spring, she got into a Twitter dispute with veteran music writer Rob Tannenbaum, who argued that singing doesn’t require the skill or work it takes to master a musical instrument. Cash shot back: “Hold on there, mister. I play both guitar and piano, and voice is the more complicated instrument.”

The tweet-feud that erupted was funny, but Cash ended up telling him, at one point: “It’s a fucking arrogant thing 2 say. U live my life as a singer for 35 yrs—the work, anxiety, diligence, Damage.”

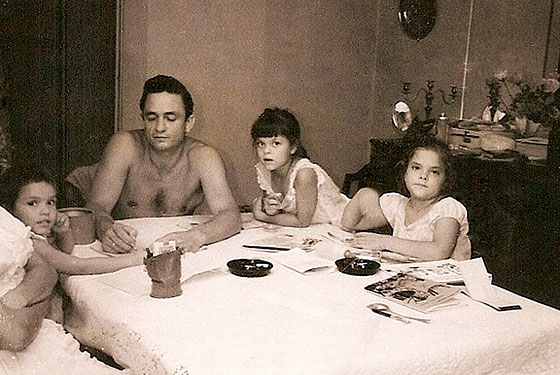

Cash spent her early childhood in Johnny Carson’s old house in Encino, California. In that hot, dry place, she developed a fear of snakes and a wariness of reporters and other wanderers who would stop by hoping to find her father. Cash’s mother, a homemaker from San Antonio, born Vivian Liberto, had a hard time with her pill-popping, often-absent husband; the marriage ended in 1966. All of this is chronicled in the 2005 film Walk the Line, which Cash finds oversimplified and painful to sit through.

From an early age, she dreamed of being a writer or poet. This was an aspiration she fulfilled, to a degree, with the publication of her 1996 book Bodies of Water, a collection of short stories written after her divorce from Crowell, when she was settling into life as a single mother in New York.

A couple of years after the book appeared, while she was starting work on her tenth album, Cash found she could not sing: Polyps had taken root in her vocal cords. The condition kept her out of the recording studio and away from concert stages for about three years. In that time, she went back to her childhood ambition, turning out essays for magazines. One of these grew into a memoir, Composed, which will be published by Viking on August 10.

The book has its share of dramatic events: her pulling the plug on her own Nashville stardom after a string of eleven No. 1 singles on Billboard’s country chart; the split from Crowell and marriage to Leventhal (“Thank God,” Johnny Cash said at the time. “I’ve been waiting 40 years for one of my daughters to marry a Jew”); the one-after-another deaths of her father, mother, stepmother June Carter Cash, and June’s hard-living daughter Rosie Nix Adams; and the brain surgery Cash underwent in 2007. All of this could have made for mere melodrama, but Cash sorts through what life has dealt her in a straightforward and understated manner; like her fourteen albums, Composed is intimate without being icky.

Among other things, the book is about finding happiness in the one city that didn’t make her feel weird. She first came to New York when she was a teenager visiting her father. It doesn’t fit the Johnny Cash legend, but he spent significant time in an apartment he owned at 40 Central Park South and stayed regularly at the Sherry-Netherland, the Plaza, and the Plaza Athénée.

“Those were some of the best memories of my adolescence,” she tells me over tea in her townhouse. “I saw Applause with Lauren Bacall and The Magic Show with Doug Henning. There were still Automats, and Rumpelmayer’s was a big deal, and the Trader Vic’s in the basement of the Plaza. My dad was not terribly strict, and he would treat you like an adult. And he exuded this love for the city.”

Cash absorbed her father’s affection for New York and, later, his wariness of Nashville. As a star of the eighties “new country” movement, she came up with catchy songs laced with insecurity and defiance and ended up with both a cocaine problem (which she got over in 1984) and a 6,000-square-foot house outside Nashville. She battled label executives along the way, and in the twenty years since she escaped the straitjacket of country-music stardom, she has remade herself into something of a New York auteur.

She has gotten by without being an amazing guitar player. Her voice is rich and complicated, but she doesn’t have the force of her musical big sister, Linda Ronstadt, or the sweetness and range of her other immediate forebear, Emmylou Harris. Even so, Cash has always had a knack for interpreting other people’s material. And luckily for her—for her sanity and sense of self-worth—she proved to be a bona fide songwriter. She has made fans out of singers like Bruce Springsteen, David Byrne, Lucinda Williams, and Rufus Wainwright, and she recently finished recording three new songs with Kris Kristofferson and Elvis Costello—perhaps the world’s most unlikely supergroup.

On a recent night, we step out of the concrete heat and into La Grenouille. Cash breezes up to the bar and joshes with the bartender. Charles Masson, the manager, sends over a glass of Champagne and writes out a Bordeaux recommendation. Here she is, the daughter of a man who escaped the poverty of his Arkansas youth, happily at home in this East Side shrine to haute cuisine. “This has to be the most pleasant place in New York right now,” she says.

Cash is, by now, a fixture of the city’s culture elite. She is a member of the Century Association, the Stanford White–designed midtown clubhouse that began accepting female members only in 1988. And she has an absurd number of well-connected friends, including Daily Show co-creator Lizz Winstead, New York Times op-ed deputy editor George Kalogerakis, Betsey Johnson CEO Chantal Bacon, and novelist Colson Whitehead.

“I have a real worker-bee mentality,” Cash tells me. She’s talking about how she built her career, but she’s really talking about everything else. This is her credo. “Just show up, just do it. Even if you feel like shit and you think you’re terrible and you’ll never get better and it will never go anywhere, just show up and do it. And, eventually, something happens.”

On a hot June day, Cash and Leventhal get into their Toyota Highlander hybrid and head to their country house in Columbia County. With Leventhal at the wheel, his iPod set to shuffle, they listen to Django Reinhardt, Boz Scaggs, and Aretha Franklin. In the passenger’s seat, with her iPad on her lap, Cash breaks the monotony with a tweet: “On long drive. Mr. L. calling my iPad a ‘digital media device’ and giving brief seminar on Django Reinhardt.”

The next day, they make their way to the Colonial Theatre in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. In a backstage room a couple of hours prior to showtime, the two of them are poking at a container of warm chicken and a bowl of limp salad. “These shouldn’t be in here,” Cash says. “It’s in my rider: No cucumbers.” She laughs, then adds, “I’m serious. I hate cucumbers.”

Sitting down to eat, Cash says she wants to start tonight’s show with “What We Really Want,” a song from the highly personal Interiors. Leventhal is against the idea, preferring to go with their usual opener, “I’m Movin’ On,” a jaunty Hank Snow number that appears on Cash’s 2009 album, The List, a collection culled from a handwritten list of 100 great American songs that Johnny Cash gave his daughter when she was an 18-year-old neophyte. Leventhal, who produced The List and came up with its impeccable arrangements, makes his case: “I’m serious, sweetie. Why would you mess with a good thing?” Speaking of “I’m Movin’ On,” he says, “it always goes over, it’s fun, it’s not all that serious. And you’ve got to build up to the wrist-slashers. You can’t just hit ’em with it from the beginning.”

Cash laughs at the term wrist-slasher. When Leventhal leaves the room, I ask her how she met him. “He came down when we were in Nashville,” she says, referring to when she was married to Crowell. “I remember thinking, ‘Oh, no, my life is going to get so complicated.’ And it did.”

At 7 p.m., husband and wife, playing as an acoustic duo, open the show with neither “I’m Movin’ On” nor “What We Really Want,” but with a compromise: “Girl From the North Country,” a tender 1963 Bob Dylan ballad that had a second life, in 1969, as a Bob Dylan–Johnny Cash duet, and is a lovely addition to The List. Mid-show, the crowd has a laugh as Cash fails miserably at the job of tuning her guitar, a problem that isn’t solved until Leventhal stands behind her and reaches around to twist the pegs. Not long after the encore (Lerner and Loewe’s “Wouldn’t It Be Loverly?”), Leventhal loads the guitars into the Highlander. Cash takes his hand and leans into him as they walk to a pub around the corner.

The polyps on Cash’s vocal cords disappeared about a year after she gave birth to Jake. She rehabbed her voice and made a cool album, Rules of Travel. She mourned the deaths of her parents and released the haunting Black Cadillac. Then, more bad news: The pesky headaches, which she had been experiencing for years, turned out to be a symptom of a serious problem with her cerebellum, which was crushing her brain stem. In 2007, she had surgery at New York-Presbyterian Hospital.

Neurosurgeons consider a day’s work serious if it means they have to cut through the brain lining, and that’s how it went in her case. I ask Cash if she worries she’s not the same person she was before surgery.

“I’m not!” she replies. “I’m totally not the same person. I have a lot more manic energy. And I experience music differently. My theory is, my brain problem was like a veil over my experience of music, and they took the veil off. It’s so great.” After surgery, she threw herself fully into writing Composed. “When you get a glimpse of your own mortality, it’s very motivating.”

Loud noises still bother her. So do certain frequencies. While doing the soundcheck for a daytime July 4 concert on Governors Island, she steps close to the microphone, only to set off a piercing feedback squall. She grabs her ears, sets down her custom Martin guitar, and leaves the stage for the nearby trailer. It takes twenty minutes to finish the soundcheck.

Despite the 95-degree weather, and the fact that the banner above the stage has Cash’s first name spelled incorrectly (“Roseanne” instead of “Rosanne”), and her discovery of cucumber slices in another backstage salad (“You know, when I put ‘no cucumbers’ in the rider, I thought I spelled it correctly,” she says), the performance is a roaring success.

Afterward, she greets fans on the grass. One of them is a nervous young man who’s clutching posters, clipped-out articles, and show bills for Cash to sign. He even has a copy of her import-only debut, Rosanne Cash, recorded for a German label.

“Oh, shit!” Cash says. “Where’d you get that? I don’t have it myself. You don’t have a shrine to me, do you?”

“I don’t have a shrine,” the fan answers. “I’m just a purist.”

“You mean completist?”

“Completist,” he says, as two security guards look on.

This summer, Cash has been playing especially charged versions of “Dreams Are Not My Home,” a song she wrote and recorded for Black Cadillac. In the kitchen of her townhouse, I ask her if the song’s titular refrain is meant to be from the perspective of her mother, who had to deal with being married to a man who often lived inside his own head.

“That’s exactly what it’s about,” Cash says, tearing up a little.

Did the song also apply to her own marriage to Leventhal, a quiet man who, I wondered, might also be someone who spends a lot of time in musical dreamland?

“Vice versa,” says Cash. “I was the one who was ungrounded and dreamy, and he is the one who pulled me back to earth, in a really good way.”

Leventhal is sitting at the kitchen table. “I’m not the dreamy one,” he says. “I’m dreamy when it comes to music, but not as far as how the world works.”

“The other day,” Cash says, “he looked up at the sky and he said, ‘Oh, God, don’t let me go first. She’ll never make it.’ I tweeted about that.”