‘I feel like the bitter old man sitting on the porch, saying, ‘Back in my day, music video was the most exciting medium to be involved in,’ ” says Samuel Bayer, who directed, among many other hits of the nineties, Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit” and Blind Melon’s bee-girl video. “MTV was a cultural barometer, stylistically influential. Whether the director was Michel Gondry or Spike Jonze or Stephane Sednaoui or Mark Romanek, people talked about videos in a way that has disappeared.”

On August 1, 1981, MTV audaciously played “Video Killed the Radio Star,” and for a little over two decades, the cable network just about did that, becoming music’s most powerful tastemaker. MTV not only made songs into hits, it launched the careers of directors, many of whom became as identifiable to music fans as Scorsese and Kubrick are to cinéasts. At their high point, these three-minute videos were as ambitious as mini-movies, with budgets that could run as much as $7 million (e.g., Romanek’s “Scream” for Michael and Janet Jackson).

Then, in the mid-aughts, in what now seems like the blink of an eye, the network virtually abandoned videos for scripted reality shows: The video star, it seemed, had been killed, too. “A few years ago, I stopped making videos,” says Jonas Akerlund, who directed “Ray of Light” for Madonna and “Beautiful Day” for U2 at the tail end of the last boom. “The budgets went down, down, down. And even if you made them for the sake of the art, nobody saw them.”

Without MTV, the record labels—already terrified of downloading—eliminated videos almost entirely, focusing instead on video-game soundtracks, ringtones, and licensing. Up-and-coming bands’ best hope was landing a spot on an iPod ad. And MTV’s star directors had mostly moved to ad work or film—like Bayer, who directed the new Nightmare on Elm Street.

But then a funny thing happened: In the last couple of years, music videos came back. “It’s a little bit like the evolution of a species,” says Gondry. “Videos found a new niche that’s habitable for them: the Internet.” And, truly, they have evolved, into a much more aggressive species. The online ecosystem is so overpopulated that the more oh-my-God bizarre a video is, the better the chance it will go viral.

Around 2005, when YouTube debuted, most viral videos were largely amateur affairs, befitting the format’s lo-fi, low-bandwidth aesthetic: the Star Wars Kid, the Dancing Baby, “Numa Numa.” Then, in 2006, a game changer: OK Go released “Here It Goes Again,” the first music video to go viral. “That video with aluminum foil on the walls and eight treadmills changed things,” says Bayer. “If Nirvana ushered in the grunge generation, it seemed like OK Go ushered in playing videos on the Internet.”

But viral hits are hard to re-create. Most bands don’t magically transform into memes overnight. And the low-budget approach that works for a nerdy-fun pop band might not sell Jay-Z records. Because one thing that hasn’t changed between the MTV era and now is pop music’s taste for polish, style, and excess. What was needed was a technological leap forward, which came in the form of a broadband explosion and 3G. With those advances, sites like Vimeo, Vevo, MySpace, and YouTube were able to support high-definition video and advertising—a development that offers something MTV never could: Vevo, for example, gives a cut of advertising revenue to the artists. “There was a time when music videos were purely promotional, and that was fine when people were buying music,” says Rio Caraeff, CEO of the Universal- and Sony-owned Vevo. “Now they’re no longer promotional. We sell advertising in and around them at a premium. Instead of being a marketing expense, videos can be a profit center.”

So far, Caraeff admits, video revenue is a “small percentage” of any artist’s livelihood, but audience numbers are so huge that the professionally produced video could become an option again. In fact, music videos on YouTube are the most-watched videos in its history, and six of the top eight most-watched across all of the Internet are music videos, topped by Soulja Boy’s “Crank Dat,” at 722 million views (as of March 23), and Beyoncé’s “Single Ladies,” at 522 million.

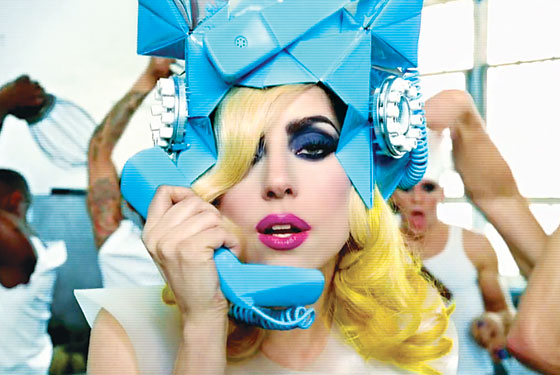

And then there’s Gaga. As Madonna and Michael Jackson were to MTV, Lady Gaga is to YouTube: the killer app. Currently she reigns with over 1 billion views—far beyond even Twilight’s combined 980 million viewers for official trailers. She, more than anyone, has made music videos relevant for the industry again, proving indisputably that they drive up record sales and concert receipts. Akerlund, who had retired from music, agreed to come back for Gaga’s star-making “Paparazzi” and “Telephone,” an insane, Tarantino-esque duet with Beyoncé. “All of this reminds me of the big days on MTV, when every job you did made an impression,” he says. “People would come up to me and say they saw my video. That didn’t happen for years, but now it’s happening again.”

What’s different now, says Gondry, is that the videos are often as important as the song. “MTV focused on the songs, even at the MTV Video Music Awards,” he says. “People call me an MTV darling, and that upsets me because I was always ignored by them. But now I feel like it’s coming back to early MTV, before the big-budget cranes, when it was creative and fun.” Better yet, it’s a lot more democratic: “The tools the nonprofessional can access for free are getting closer to the tools you use when you have tons of money,” says Gondry. That means the low-budget and fan-made are just as likely to blow up as an epic by Gaga.

In addition to MTV vets like Jonze (who recently directed the messy and hilarious “Drunk Girls,” for LCD Soundsystem), there’s a whole new wave of boundary-pushing auteurs coming up—provocateurs like Romain Gavras, the son of filmmaker Costa-Gavras, who directed the gory, banned-by-YouTube evocation of M.I.A.’s “Born Free,” and Vincent Moon, a French director with no interest in working for anything called an “industry.” He speaks for a lot of his peers when he says, “About the music industry, I have no fucking idea. Frankly, I think it’s dying. I really hope that it does, in fact.”