Hot Sauce Committee Part Two, out May 3, is, according to the Beastie Boys, a return to their fundamental smartassery after 2004’s uncharacteristically serious To the 5 Boroughs, which was, in part, an attempted palliative for post-9/11 New York City. Explains Adam “Ad-Rock” Horovitz, one third of the group alongside Michael “Mike D” Diamond and Adam “MCA” Yauch: “Most of the shit we do is go down to the studio and try to make each other laugh.” That’s been the M.O. since the band first formed, in the early eighties, as high-school kids playing hardcore music—the rawer, faster subset of punk rock that was just developing. It would be another new genre, of course, that would make them legendary: By mid-decade, with the release of Licensed to Ill, their 1986 debut on Def Jam Records, and its massive success, the Beasties were unlikely hip-hop superstars.

Hot Sauce follows the release of “Fight for Your Right Revisited,”a surreal, 30-minute sequel to the original “(You Gotta) Fight for Your Right (to Party!)” music video for the band’s first hit single off Licensed to Ill, which is celebrating its 25th anniversary this year. To mark that occasion, a look back at the birth of the Beastie Boys sound, as told by the people who lived it.

1981

The Beastie Boys’ initial lineup was Diamond on vocals, Yauch on bass, John Berry on guitar, and Kate Schellenbach—later of Luscious Jackson—on drums, a core that had grown out of a previous group, the Young Aborigines. Horovitz was fronting his own punk band, the Young and the Useless, which would often split bills with the Beasties.

Michael Diamond: I went to Walden, this hippie school on the Upper West Side, and there was a student lounge with a record player, so between classes or if you were cutting class, you played records. There was a kid I was friends with who brought in Kurtis Blow’s “Christmas Rappin.” I was a little punk-rock kid, and I also liked dub and reggae. And then the second I heard hip-hop, I was like, “Oh, now I’ve got another one. I’m gonna love this.”

Dante Ross, friend and, later, Def Jam A&R exec: Hip-hop was black punk rock. It was dangerous, it was rebel music, and it just seemed like a natural evolution.

Diamond: We’d buy every [rap] twelve-inch when they came out and be really excited about them, and the next thing you do is you listen to them over and over and memorize every rhyme.

Kate Schellenbach: We’d sit around with my little RadioShack tape recorder, where you have to push down the two buttons at the same time to record, and Yauch would rap over [the Sugarhill Gang’s] “Apache.” He had the deepest voice, so he was the most believable. At one of these sessions, me, Yauch, and our friend Sarah Cox started a rap group called the Triple Sly Crew. At least it was a group because Adam made us buttons. We never performed or anything, but we had the buttons. Beastie Boys was a button first, too. John [Berry] and Yauch were making Super 8 films and badges and buttons. That’s when they came up with “Beastie Boys.” For a button.

Darryl Jenifer, bassist for hardcore pioneers the Bad Brains: We all used to hang out around the Ratcage Records store on Avenue A. It was almost like we were in college, like Ratcage was the quad. [The Ratcage label would later release the Beasties’ first EPs and singles.] We were up there eating pistachios, drinking soy milk, and we’d be selling a little ganja on the strip—selling our nickel bags to get our music going. And we would yell, “Beast! Beast!” when the cops would come. Mike and Adam and Adam used to be on the stoops, yelling it back to us. That’s where I believe “Beastie Boys” came from.

Tim Sommer: I had a radio show at WNYU called “Noise the Show,” and the whole hardcore scene had coalesced around it. In the early fall of 1981, I started getting phone calls from these screechy voices: “Play the Beastie Boys, play the Beastie Boys.” I’d never heard of the Beastie Boys. At one point I got whoever was calling, either Diamond or Yauch, to admit that there was no such thing as the Beastie Boys. It was an idea that they fooled around with, but they hadn’t done anything yet.

Eric Hoffert: My band the Speedies were extremely popular in New York until about 1981, and the Beasties came to all of our shows. Then when I went to NYU, me and my cousin David took our four-track up to [John’s loft on] 100th Street to record [the Beasties’ hardcore EP Polly Wog Stew]. I remember them as thoughtful, reflective, intelligent, intense kids. They were respectful, and they asked us to record them. What they became later, that was very different.

Diamond: I remember seeing the Funky Four Plus One More at the Rock Lounge on Canal Street. It was a club that we’d all go to anyway, and these hip-hop groups from the Bronx would come downtown. That was a really mind-blowing thing.

Adam Horovitz: We were like 15, so the thought of going up to the Bronx [to see hip-hop]? We stayed downtown. People talk about how awesome Area was. Area was great, but Danceteria was fucking awesome. It was three or four stories. Bands would play on the ground floor, and then there was a hardcore dance club, and then there was a lounge above. You’d see, like, Billy Idol and all these people getting fucked up. And all these kids.

Diamond: The people at the clubs at the time, they liked having kids there just ’cause they were into the music. Fortunately, and I don’t really know why, they were very nice to us.

Horovitz: In high school [at McBurney], me and our friend Nick Cooper were on Saturday-morning detention every week. I remember going to the after-hours club Berlin until three in the morning, then going straight to Saturday-morning detention.

Schellenbach: Sometime in 1982, John Berry left. He wasn’t into playing music. He kind of went off on a drug-induced tangent. Horovitz was already hanging around, he already knew all the songs. As he says, he came up from the minors.

1983-4

The band recorded a four-track EP, Cooky Puss.The title track—a genre mash-up built around a prank phone call Horovitz made to a Carvel ice-cream franchise asking to speak with Cookie Puss, a character heavily featured in Carvel’s advertising—became an underground hit. It was more comedy than actual hip-hop, but it caught the ear of the burgeoning hip-hop cognoscenti, eventually leading to a working relationship with Rick Rubin, then an NYU student. Rubin would co-found the label Def Jam in 1984 with Russell Simmons, then the manager of many of the genre’s top acts, including his brother’s group, Run DMC. The Beasties would spend a lot of time at Rubin’s dorm, Weinstein, both working and partying, and Rubin would become a close collaborator, instrumental in crafting the Beasties’ new sound—a sound that made rap accessible to white kids everywhere, not only because the three were white but because they incorporated recognizably white music in their beats. But their Beastie Boys personae were entirely their own: reckless, debauched, Budweiser-spewing goofballs.

Schellenbach: There was this friend of Yauch’s dad; I remember him being a commercial-jingle producer. He let us come to the studio after hours to record. They had Popov vodka in the cabinets. We started making prank phone calls, and it was a studio, so we could record everything. I don’t know who had the idea to actually call Carvel and [ask to speak to] Cookie Puss, but Horovitz put on this accent … I never laughed so much in my life.

Diamond: “Cooky Puss” wasn’t a song we really could replicate live. It was a bunch of segments of stuff that we’d played, like, chopped up, and the phone call. But that started getting played in clubs, and all of a sudden we got asked to do shows in places we’d never been.

Nick Cooper, friend: They caught on to everything that was interesting that was happening in music then. There was a real organic sense of purpose around them that I’m not sure they were aware of. They accidentally knew what they were doing.

Schellenbach: You’d see [break-dancers] Rock Steady Crew; they had matching T-shirts, so we all went to Bleecker Street to get matching Carvel T-shirts with our names ironed on. And everyone had to come up with hip-hop names. I think mine was Kate Your Mate.

Horovitz: People used to say “Rock” at the end of their graffiti name. I wish I had come up with something different, like “Delirious.” I might change it.

Thurston Moore, Sonic Youth: I saw the Beastie Boys at [nonprofit art space] the Kitchen, of all places. I remember Mike D looking out at the audience and saying, “I don’t know if we can keep playing, because everybody out here is old and has beards and you’re sitting down.” He was really funny, and when he played, he was phenomenal. He was this rag doll of a singer; he would jump up and fall down on the stage, just like splat.

Horovitz: Then we were like, “Oh, shit, we should get a D.J.! Like rap groups. They have a D.J.!” Nick Cooper knew about this guy Rick Rubin who went to NYU and would throw parties and had turntables. And a bubble machine. We were like, “If we had a fucking D.J. and a fucking bubble machine, we’d be fucking killing it.”

Adam Dubin, Rubin’s NYU roommate and co-director of the video for “Fight for Your Right”: Rick was very excited by “Cooky Puss.” He organized me and our other friends to call in to “Noise the Show” and request it, and then, after they played it, to call in again and say how much we liked it. He had no financial stake then.

Hoffert: Rick Rubin was in a hardcore band called Hose. They would play downstairs in the cafeteria of the Weinstein dorm. It was crazed, almost Charles Manson–like. They were pretty awful. And people couldn’t make sense of what he was onto—the fact that he was in this band, and then he’d come back from these hip-hop clubs at night. He was already a budding impresario. He was a complete powerhouse; he worked fourteen, sixteen hours a day.

Dubin: Rick’s most famous dorm party was the bikini contest. It was about 150 people. Packed. Everything about it was unsafe. Surging crowds, straight vodka, gin, tons of beer. Finally the time rolls around for the bikini part, and girls start stripping and people start throwing drinks. I kind of remember Adam Horovitz pouring water over some of those girls.

Horovitz: So then Rick Rubin becomes our D.J.: D.J. Double R.

“They were smart, arty Jewish boys from New York City, and they created these white-trash burnout characters. And they pulled it off.”

Diamond: [At gigs] we’d probably play hardcore songs for fifteen minutes, then put down our instruments, and Rick would D.J. and we’d do another ten minutes. We’d basically be doing bad cover versions of those twelve-inchers live. Maybe each of us would say eight rhymes that we wrote. You emulate the music that you love, and then after a minute you start to figure out your place in that.

Cooper: They played a show at Studio 54 right when it reopened after being shut down for tax evasion. We had a case of beer in the dressing room, and security realized they were all minors, and they took it away. Diamond started complaining onstage about it, saying, “These Mafia owners, these corrupt people, these scumbags.”

Horovitz: One night at Danceteria, Rick was like, “Yo, this guy is Run’s brother. He’s the manager of fucking Run DMC.” And it’s Russell Simmons.

Schellenbach: Around that time, I got back from being away, and I ran into the guys at Area. They were all wearing matching Puma sweatsuits that Rick had bought them, and of course he didn’t buy one for me. I respected him as a musician, but he and I did not get along. He was like a meathead sexist asshole. He flat-out said, “I don’t like the way women sound rapping.” It was already something I felt insecure about. Yauch had a heart-to-heart with me: “Rick thinks we can be the first white rap group. We’ll still do the [hardcore] songs, but we’ll do it as the Young and the Useless.” We did that for a while.

Ross: Jazzy Jay had gotten close to Rick, and he invited all those dudes up to the Bronx, and the Beasties went and got the Zulu beads and were put in the Zulu Nation [the international hip-hop-awareness group formed by Afrika Bambaataa]. That was big for them.

1985

The band, still largely unknown, lucked into some settlement money when British Airways sampled one of the Cooky Puss songs, “Beastie Revolution,” without clearing it. Yauch and Diamond used the cash to move out of their parents’ houses. Even more lucky, the Beastie Boys landed an opening slot on Madonna’s “Virgin Tour.” According to the book Def Jam, Inc., Madonna’s management had originally called Russell Simmons inquiring about the hip-hop trio the Fat Boys. Without actually making it clear that he did not, in fact, manage the Fat Boys, Simmons talked Madonna’s people into using the Beasties.

Diamond: Yauch and I got an apartment in Chinatown—apartment might be an overstatement. It was on Chrystie Street when it was still really Chinatown, and it was an entirely sweatshop building. We could play music literally any time of the day or night.

Diamond: I did go [to Vassar] for a semester, and it was hard. I had to go [to my mom] and say, “It’s a total waste of your money and my time, because all I want to do is be in this band.” Rick and Russell were like, “You’re gonna make a video for ‘She’s On It.’” And in our minds, we were the biggest deal in the entire world. Our friends might not have agreed. But you know what I mean—all of a sudden we were making a video, and it started to get shown. We were big on the local video channel U68.

Ross: They went up to perform at the Apollo, and Beastie Boys shows at this point were a little haphazard at best. But by the second song, Mike D’s doing the Jerry Lewis, and the whole Apollo Theater is going, “Go, white boys! Go, white boys!” In my head I’m like, “My friends are gonna be famous!”

Horovitz: And then the Madonna tour happened. We did like three songs, and then I did the electric boogaloo for a minute, and then we fucked with the audience. They hated us. Kids literally in tears, parents wanting to kill us. It was awesome. They wanted to kick us off the tour, and Madonna was like, “These guys are staying, these guys are great.” We got back to New York, and we were really feeling ourselves. We were crushing our old spots.

Diamond: Then it was like, we could go to our old spots as a full-time occupation. As far as we were concerned, we were getting paid to go to those places.

1986

While on the Madonna tour, Yauch and Diamond had given keys to their Chinatown apartment to their buddies, who promptly trashed the place beyond habitability. Diamond’s new apartment, on Hudson Street, became unofficial headquarters. The band was now working on the music that would become Licensed to Ill. Before its release, in the fall, the trio would hit the road as Run DMC’s supporting act on the “Raising Hell” tour, which cemented their stage characters: Generally speaking, MCA was the bad boy, Ad-Rock the cute one, and Mike D the comedian.

Horovitz: That year was basically Mike’s house during the day, writing lyrics, going to the club, going to the studio, going back to the club. We would write and write and write, then read the lyrics out loud to see who liked what. And that’s kind of how we’ve always done it since then. Rick had a drum machine, and I used to go to his dorm room and make beats. I made the beat for LL Cool J’s first single, “I Need a Beat.” I bought an 808 at Rogue Music [the Roland TR-808 was one of the first programmable drum machines] with some of the settlement money.

Diamond: We would start with the music, and then Rick would clean it all up. Rick had the ability to make things sound legitimate and bigger, to make it sound like a record.

Rubin: Each one had a strong personality. When we came up with rhymes, we tried to cast them for the right character and the right voice.

Horovitz: It just sort of happened. It wasn’t like, “Okay I’m going to be like Melle Mel, you’re Kool Moe Dee.”

Diamond: We never broke it down like, “Okay, I’m the baritone.”

Chuck Eddy, music writer (who did a notorious Beasties piece in 1987 for Creem): They were smart, arty Jewish kids from New York, and they created these white-trash burnout characters with the help of Rubin. And they pulled it off.

Horovitz: One night at the studio, me and Adam and Mike, we’re waiting outside, drinking beers, and we see Run running down the street screaming, and DMC is way behind him. They were so excited: They’d come up with the idea for our song “Paul Revere” on the way there. We loved Run DMC—and then we were on tour with them. It was like: “Wow, if we’re hanging around with these dudes, it must mean we’re all right.”

DMC: For the first couple of days of the tour, the towns we were playing were in Alabama, Florida, Tennessee—this was the black South. We expected to hear boos, so we were reluctant to be on the side of the stage, to see them get disappointed. But then from the dressing room, we’d hear “Yeaaaaaah! Yeaaahhh!” It was the black audience, praising these dudes. The reason they were so good: It wasn’t white punk rockers trying to be black emcees. They wasn’t talking about gold chains or Cadillacs. They were white rappers rapping about what they did. Real recognize real.

Run: They’d teach me about stupid white-boy stuff, like whippits. “What the hell is a whippit?” “Okay, you take this Reddi-wip thing, you push, you inhale it.” Stuff black people don’t do. I was like, “I don’t know the effects of this foolishness.” I don’t think I did it. With the Beasties, nothing was normal. Ad-Rock bugged me out: He was dating the actress [Molly Ringwald]. It was like, “Wow, now that I look at him, he kind of looks like a movie star.”

Molly Ringwald: I finished doing The Pick-Up Artist, and the producer was putting together the music. He brought the Beastie Boys in to talk to them about having a song in the movie, and Adam gave his number to the producer. I went and looked at some music magazines. I was trying to figure out which Adam it was, because I only wanted to call if it was Adam Horovitz. I thought he was really cute.

DMC: The backstage would be so full of beer. I remember one night we got scared. Yauch, he slipped, like it was a banana peel, and went 50 feet in the fucking air, and went down like bam. I know he was hurt. But he just gets up and laughs it off.

Ringwald: I only made it two weeks on tour. I remember New Orleans because I got really drunk—drunker than I’d ever been in my entire life. I drank all the Beastie Boys under the table.

Run: I never hung out late-night, but I would read all the crazy stuff in the tabloids. In my mind, I was wondering, What percentage of this is true? “Oh, man, the Beasties didn’t turn over a car last night, did they?” They were becoming a menace to society.

“They wanted to kick us off the tour, and Madonna was like, ‘These guys are staying; these guys are great.’ ”

1986

Def Jam released Licensed to Ill, which was a near-instant success, becoming (Def Jam distributor) Columbia Records’ fastest-selling debut and introducing classic Beastie rhymes like this one off “Time to Get Ill”: “Went outside my house, I went down to the deli / I spent my last dime to refill my fat belly / I got rhymes galime, I got rhymes galilla / And I got more rhymes than Phyllis Diller.” The album would go on to sell 9 million copies, good for sixth on the all-time rap-sales list. In support, the band set out on their first headlining tour.

Eddy: There was something knowing and thought-out about what the Beasties did, connecting rhythmic seventies rock with rap. I kind of knew it was going to happen [eventually]. I was waiting for Licensed to Ill.

Dubin: It was crazy. D.J.’s were spinning “Fight for Your Right” every hour. On the set of [the Run DMC movie] Tougher Than Leather, executives from MTV came down and said, “We’re holding a spot in heavy rotation. We need a music video.” We shot it in two days. The idea was to present who the Beastie Boys are: They come to your party, they wreck the party, they steal the girl, they drink all the booze, and when all hell breaks loose, they leave. [Co-director Ric] Menello came up with the high-minded idea: It’s the party scene from Breakfast at Tiffany’s.

Tabitha Soren, future MTV V.J. and Rubin’s friend from NYU: They had no budget. They stole expired whipped cream from behind the back of a grocery store. So there’s this raunchy-smelling, past-its-prime dairy stuff being thrown all over. If you watch the video very carefully, I’m the only person who doesn’t get whipped cream in their hair.

Horovitz: Then Russell booked us our first headlining tour. It all started in Missoula, Montana. And it was super-weird.

Lyor Cohen, who was Run DMC’s road manager before spearheading Def Jam’s management arm, Rush Artist Management: In the beginning, they were booked in 400-to-700-seat clubs. By the time we got to California, I had to change the venue six times, from a 700-seater to a 16,000-person-capacity venue.

Rubin: I remember Volkswagen doing an ad with their car with the hood ornament ripped off—behavior inspired by Mike D’s necklace. In that moment, it was clear we were part of the public consciousness.

Horovitz: Literally everything we did was just with our friends. And all of a sudden we’re going to Europe and the U.K., and it was us and all of our friends in fucking Tokyo. It was just crazy.

Rubin: I stopped touring to stay in New York and produce music, so it wasn’t as hard on me. They had to deal with “Beastie Mania” firsthand.

Cohen: It was insane. I’ve been doing this for 30 years. It’s only happened once.

Ringwald: In England, the police basically came and got Adam [Horovitz] in the middle of the night because they said he threw a beer bottle and it hit this girl. It was a really rowdy audience, super-drunk, and they were throwing beer cans at the stage. Adam picked up a baseball bat like he was going to bat them back, but it was Yauch who actually threw the bottle. And Horovitz never said that it was the other Adam, which says something about why the band is still together. At this point, Adam was really burnt out. He felt a little trapped in their image. You know, the record company wanted to put them onstage with go-go dancers. He kept saying, “Don’t people realize it’s just a joke? That it’s stupid?” And we’d kind of fallen in love, and he wanted to hang out with me, and I wanted to hang out with him. It was also a really weird time for him: He’d lost his mom not that long before, and he was still reeling from that.

1987

Amid all that success, the relationship between Rubin and the Beasties—who were chafing under their friend’s Svengali-like public image and upset by Def Jam’s withholding royalty payments—began to disintegrate. Meanwhile, Simmons and Rubin were having their own difficulties, thanks to competing visions for the future of Def Jam; they would later split up as well.

Rubin: The press had a negative effect. The band members were portrayed as my puppets, which wasn’t the case, and they harbored resentments about that. Also, things grew so quickly, none of us knew how to handle it, and we all got pulled in different directions. Everything happens the way it’s supposed to. It’s out of our control.

Dubin: They had a great collaborator in Rick, who knew how to take their music to the next level. For a time, he helped to steer them, and they were happy to be steered. But that was a very brief time. And I’ll tell you this: Rick didn’t tell them what to do onstage.

Cohen: We were young, and had we had any experience, they would have still been with us. I probably would have been a better collaborator and a better diplomat between the band and Rick.

Horovitz: It all just fell apart and got fucked-up. Which was sad, because it was really fun. But what are you gonna do?

DMC: I commend the Beastie Boys for [leaving Def Jam]. They were able to go away and keep their identity. It wasn’t defined by “Oh, the label wants this song.” That’s why they still have their following. I’m so jealous.

2011

The Beastie boys went on to make six more studio albums, selling a total of more than 42 million copies worldwide and setting trends in video, fashion, and pop culture. Their eighth album, Hot Sauce Committee, was temporarily shelved in 2009, when Yauch was diagnosed with cancer in his parotid gland and in a lymph node (for which he continues to be treated; he was unavailable for this oral history). It was restarted in 2010—hence the Part 2. Despite its weighty backstory, Hot Sauce finds the Beasties returning to the vibe that began with Licensed to Ill; on the track “Make Some Noise,” Yauch raps the lines “We got a party on the left / A party on the right / We gonna party for the motherfuckin’ right to fight.”

Horovitz: At the time [of 5 Boroughs], our usual stupid shit wasn’t that funny.

Diamond: There wasn’t a big heavy event that transpired while we were making Hot Sauce. We were free to get back to our bread and butter: fart jokes.

See Also

• Hot Sauce Committee Part Two Posted Online

• Watch the Fight for Your Right Revisited Video

• A Guide to Every Celebrity Cameo

• Odd Moments in Beastie Boys History

From left, Adam Yauch, Mike Diamond, and Adam Horovitz. Photo: Ebet Roberts/Redferns

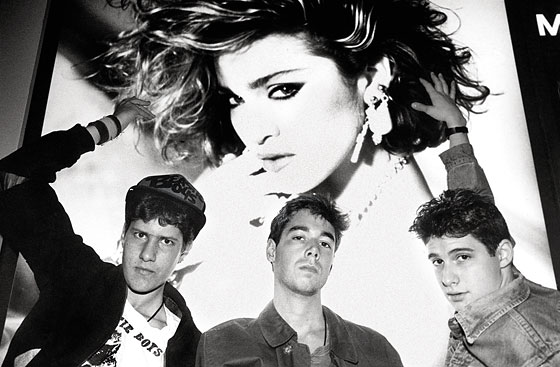

On the Madonna tour. Photo: Glen E. Friedman

With D.J. Rick Rubin. Photo: Josh Cheuse/PYMCA/MusicPictures

Horovitz and Ringwald. Photo: David Plastik

On the 1986 tour with Lyor Cohen (center, with glasses). Photo: Courtesy of Lyor Cohen

Photo: Thomas Rabsch