In the spring of 2001, the Beninese guitarist Lionel Loueke flew to Los Angeles to audition for the elite tuition-free jazz graduate program at the Thelonious Monk Institute. Loueke was 27 and had lived in the U.S. for just two years. He hadn’t heard a Miles Davis record until after he turned 20. There were about a dozen finalists, and Loueke was the next-to-last to perform. Across from him sat a panel that included Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter, and Terence Blanchard—three of the most famous jazz musicians alive. They asked Loueke to play “Footprints,” one of Shorter’s own tunes. Loueke swallowed hard, threaded a piece of paper between the strings of his guitar to mimic the sound of a percussive thumb piano called a kalimba, and began an introduction that fused traditional African sounds with post-bop jazz. “I remember saying to myself, ‘This guy is crazy or brilliant,’ ” Blanchard told JazzTimes years later. When Loueke finished, the judges broke into applause. Shorter hopped up and exclaimed, “I told you I’m from Africa, and this is my brother!” Hancock half-joked that Loueke should skip out on school and hit the road with him. (He eventually did, and the two still collaborate.) “I pretty much knew the result before I got out of the room,” Loueke says.

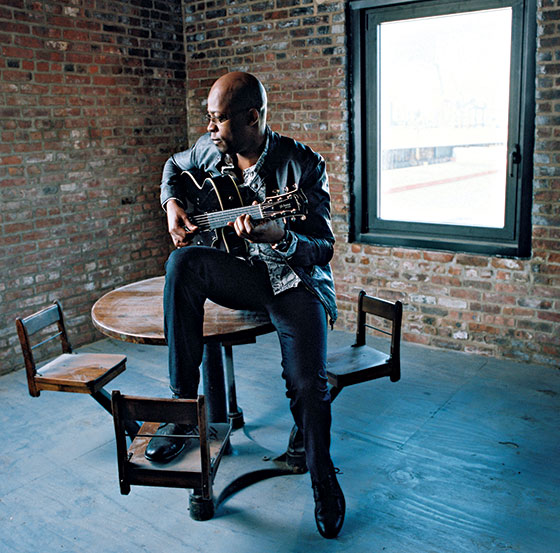

Seeing Lionel Loueke take the stage today, it’s not hard to see what so impressed that panel of jazz legends. Tall and lithe, with a velvety West African French–accented baritone, Loueke exudes a seductive effortlessness. He can play fast and loud, but it’s nearly impossible to imagine him ever fretting over a difficult passage. It’s not that his music is without intensity, it’s that the intensity is of the most smoldering, in-control variety.

Loueke’s new album, Heritage (out August 28; he’ll be at the Blue Note September 4 through 6), almost makes sport of his profound cool. On the introduction to the opening track, “Ifé,” Loueke simultaneously sings in Yoruba, adds tribal clicks, and darts up and down his guitar with preternatural confidence. On the second track, “Ouidah,” he plays an improvised call-and-response with keyboardist Robert Glasper that heats up without ever quite exploding. On “Hope,” Loueke recites verses in his native Fon over a heavy groove, sounding a little like a Francophone Morgan Freeman playing God.

The son of a math professor and a teacher, Loueke didn’t pick up a guitar until he was 17. During a few years’ study at a conservatory in the Ivory Coast, he spent his off-hours transcribing solos from old jazz records; later, in Paris, he skipped the nightlife and stayed home evenings to practice. At Berklee College in Boston, he refined his group approach with his still-frequent collaborators bassist Massimo Biolcati and drummer Ferenc Nemeth. At the Monk Institute, he completely reinvented his technique, just as he was beginning to gig with Blanchard. Even now, with a major-label contract and a steady gig with Hancock, he’s anxious to refashion himself. (“If I could take six months off and just lock myself in and practice, I would be so happy.”) To that end, he’s engaged in some intense self-study: On trips home to Benin, he’s taken a tape recorder to villages to document the traditional rhythms that he heard buried in his own playing. “It was important for me to just go and see all those differences, so I could relate to what I’m already doing and then move it to another place,” he says.

Heritage is a further step into that other place, and its funk textures are just Loueke’s most recent exploration, not a move away from his homeland. His next project, he hopes, will be the first album that he’ll record in Africa, enlisting both an American string quartet and traditional African percussionists. “You just make a circle, give everyone some drinks, set up some microphones, and just record,” Loueke muses. “We’ll have no light except for moonlight. That’s when you’ll hear real music of the continent.”

Heritage

Lionel Loueke.

Blue Note Records. August 28.